What Changed in China Tech | Issue 2

Chinese Chip IPOs: Breakout or Bailout?

Editor’s Note: Most China tech coverage tracked the chip IPO frenzy by counting valuations and first-day gains.

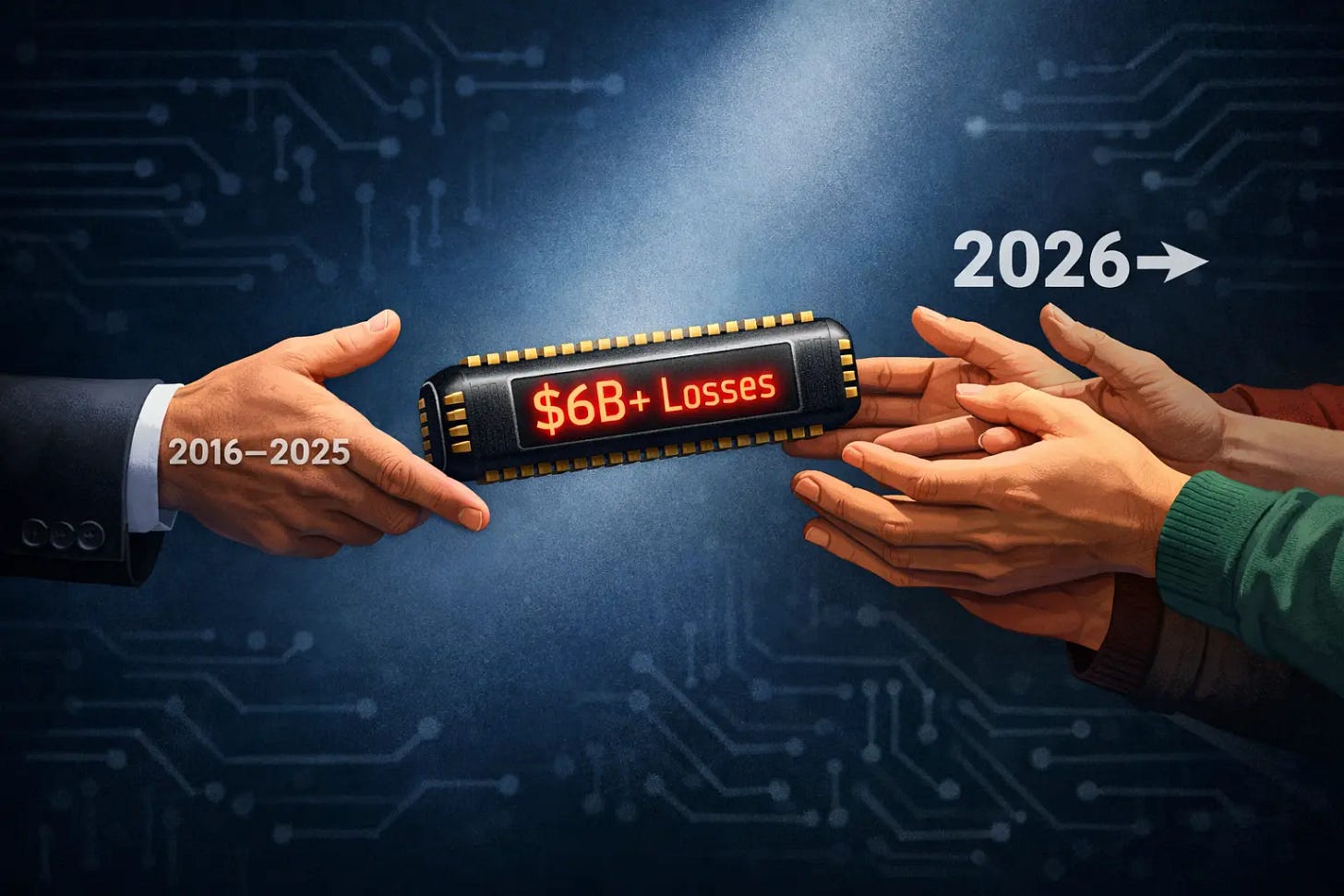

This one asks a different question: When seven chipmakers rush to public markets within 90 days despite cumulative losses exceeding $6 billion, what does the timing reveal about who’s running out of patience—and who’s stepping in to take their place?

Each issue of What Changed highlights concrete signals, surfaces one hidden variable that explains why they matter, and points to what deserves attention next.

Published most Thursdays when genuine directional shifts emerge. Read more about this series →

The Question

On January 2, 2026, Biren Technology’s stock surged 76% on its first trading day in Hong Kong. Retail investors piled in, pushing the GPU maker’s market cap above $10.6 billion. Not bad for a company that has never turned a profit and burned through over $4 billion since 2019.

Biren wasn’t alone. Just days earlier, ChangXin Memory Technologies (CXMT), China’s only large-scale DRAM manufacturer, filed to raise $4.2 billion on Shanghai’s STAR Market (China’s Nasdaq-style tech board for tech companies), despite accumulating $4.4 billion in losses over three years. Earlier in December, two other GPU makers, Moore Threads and MetaX, went public with balance sheets still deep in red.

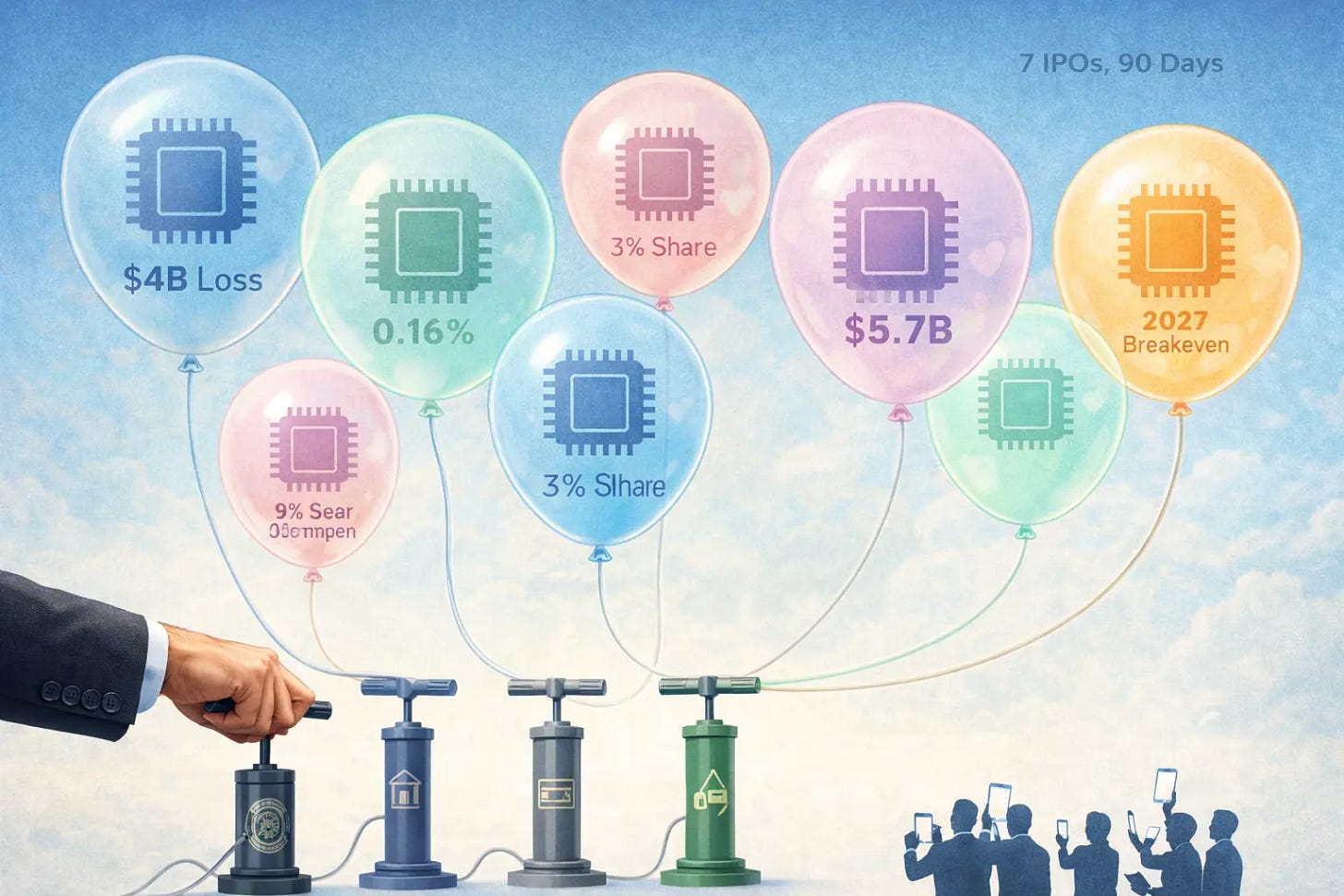

This wave of loss-making IPOs follows a different rhythm than market-driven success. It’s the choreography of a managed handoff. We’ve tracked Chinese GPU makers’ fundamental challenges before: sub-3% combined market share, cash burn exceeding revenue fourfold, profitability timelines pushed beyond 2026. Those problems haven’t disappeared. What’s changed is the funding source. Between late 2025 and early 2026, China’s chip industry entered a critical phase shift: the transition from private capital to public markets. These companies clearly haven’t “made it.” Why is Beijing orchestrating this IPO wave now, and is it extending the runway for genuine breakthroughs or just socializing losses before the reckoning arrives?

We tracked five signals that reveal the mechanics of this handoff.

Five Signals

Biren Technology’s listing mechanics revealed how state capital manufactures market enthusiasm. The GPU maker raised $750 million in August 2025 at a $2.6 billion valuation. Four months later, public markets valued it at $10.6 billion, a 4x markup. The fundamentals we’ve documented (Biren generated just $47.8 million in revenue for full-year 2024, with first-half 2025 revenue at $8.3 million) didn’t improve. What changed was the investor base: 23 cornerstone investors (institutions that commit capital before the public offering) put in $375 million upfront, providing a price floor that gave retail investors confidence to pile in. The result: 2,348x oversubscription in the retail tranche. Strip away the frenzy and the pattern becomes clear. This was state-backed capital creating the appearance of market validation to attract retail money.

CXMT’s $4.2 billion fundraising target tells a different story but reaches the same conclusion.Unlike GPU makers still burning cash on R&D with distant profitability timelines, CXMT disclosed that it expects to turn profitable in 2025, with net income projected at $280–490 million, and achieve full-year profitability in 2026. The memory maker’s 2025 revenue is forecast at $7.7–8.1 billion, up 127–140% year-over-year, driven by DRAM price recovery and capacity expansion. Yet CXMT still carried $5.7 billion in accumulated losses as of September 2025. The company holds 4% of the global DRAM market, a toehold in the industry. The IPO serves a specific purpose: securing the $4.8 billion in total capital commitments needed for next-generation production lines before the current funding cycle runs dry. CXMT also became the first company to use STAR Market’s new “pre-vetting mechanism,” completing two rounds of regulatory review before formal filing to avoid disclosing sensitive technology details prematurely. The message: even China’s most successful chipmaker still needs massive capital infusions and regulatory protection.

The concentration of IPO filings in Q4 2025 through Q1 2026 reflects coordination, not coincidence.Moore Threads and MetaX debuted on STAR Market in December 2025, both posting triple-digit first-day gains despite ongoing losses. Enflame Technology completed listing guidance. On January 1, 2026, Baidu announced that its AI chip unit Kunlun had confidentially filed for a Hong Kong IPO targeting up to $2 billion. Illuvatar officially listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange this week (January 8). At least seven major chip companies moved toward public listings within 90 days. The timing aligned with two external pressures: U.S. export controls tightened in December 2024, raising urgency to secure capital before technology access narrowed further; and Beijing’s policy shift toward “sustainable growth” over pure scale forced companies to demonstrate profitability roadmaps in prospectuses. The clustering signals something beyond individual corporate decisions. It’s a managed transition orchestrated to prevent a funding cliff that would collapse the sector.

Shareholder lists revealed who needed exits and who was providing them. CXMT’s prospectus showed that while China’s state-backed National Integrated Circuit Fund (known as “Big Fund”) held 8.73%, early private investors including Alibaba, Tencent, Xiaomi, and venture firms also held stakes dating back to 2016, nearly a decade of losses. Biren’s shareholder list showed Tencent as the largest institutional shareholder after six funding rounds, alongside government funds from Shanghai and Hefei. These private backers, including tech giants who initially invested to secure chip supply chains, had reached the limits of patience. Venture funds operating on 7–10 year cycles needed exits. But local governments couldn’t allow M&A consolidation without destroying their industrial development narratives. IPOs became the only liquidity pathway that satisfied both groups: giving private investors exit options while keeping companies operationally independent to satisfy government stakeholders.

Baidu’s Kunlun pivot from independent funding to IPO captured the structural shift in real-time. Kunlun completed Series D funding in July 2025. By December 20, Baidu announced it was evaluating a spin-off listing. Twelve days later, on January 1, 2026, confidential filing was submitted for a Hong Kong IPO. The prospectus disclosed that Kunlun had shipped over 69,000 AI accelerators in 2024, ranking second domestically behind Huawei’s Ascend. Yet it remained deeply loss-making. Goldman Sachs estimated Baidu’s 59% stake at $3–11 billion, while Macquarie valued it at $16.5 billion. A valuation range so wide reflected fundamental uncertainty about when, or whether, profitability would arrive. Kunlun’s case illustrated a hard constraint: as China’s AI chip sector matured, standalone private funding rounds couldn’t provide the scale of capital needed for next-generation products. Public markets became the only funding source deep enough to sustain multi-year development cycles. The six-month acceleration from Series D to IPO filing stems from necessity.

Hidden Variables

Call these IPOs what they are: handoffs, not success stories.