The Credential Economy: Why AI Chip Performance Isn’t Enough in China

When $14M in chips sit idle, that’s not failure. That’s the point.

On December 7, Baidu made an unusual announcement. The company was evaluating–not committing to–a spin-off of its AI chip unit Kunlunxin. The public filing included an explicit disclaimer: “The company does not guarantee the proposed spin-off will proceed.”

Why announce a plan you might cancel? Because two days later, the answer arrived.

Donald Trump declared he would allow Nvidia to export H200 chips to China. The announcement lifted the Biden administration’s most stringent export control on advanced AI processors.

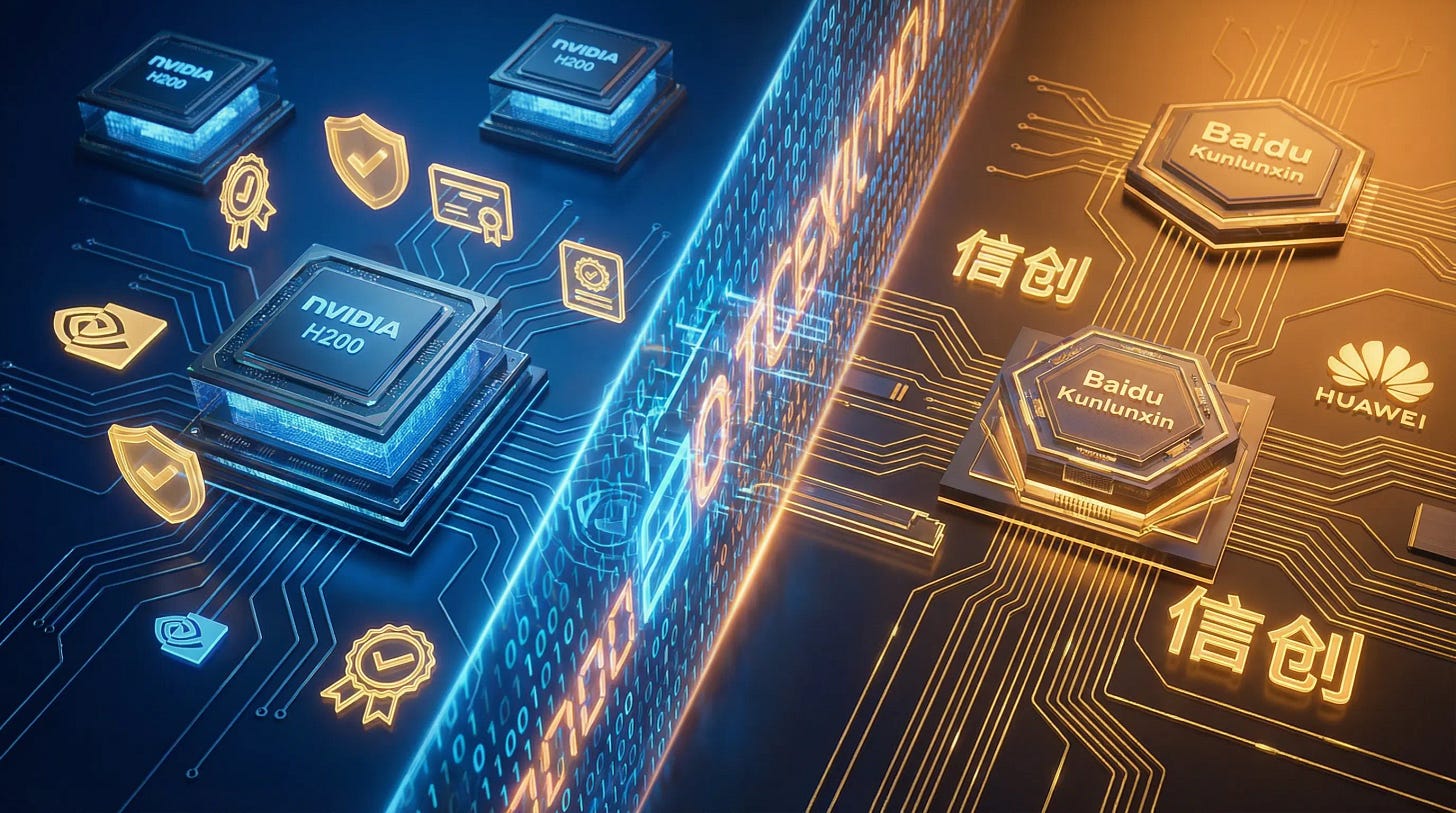

The same week, Beijing formalized a government procurement list mandating domestic AI chips for public sector buyers. The Financial Times reported that Chinese regulators were preparing approval requirements for H200 purchases. Companies would need to prove domestic alternatives cannot meet their needs.

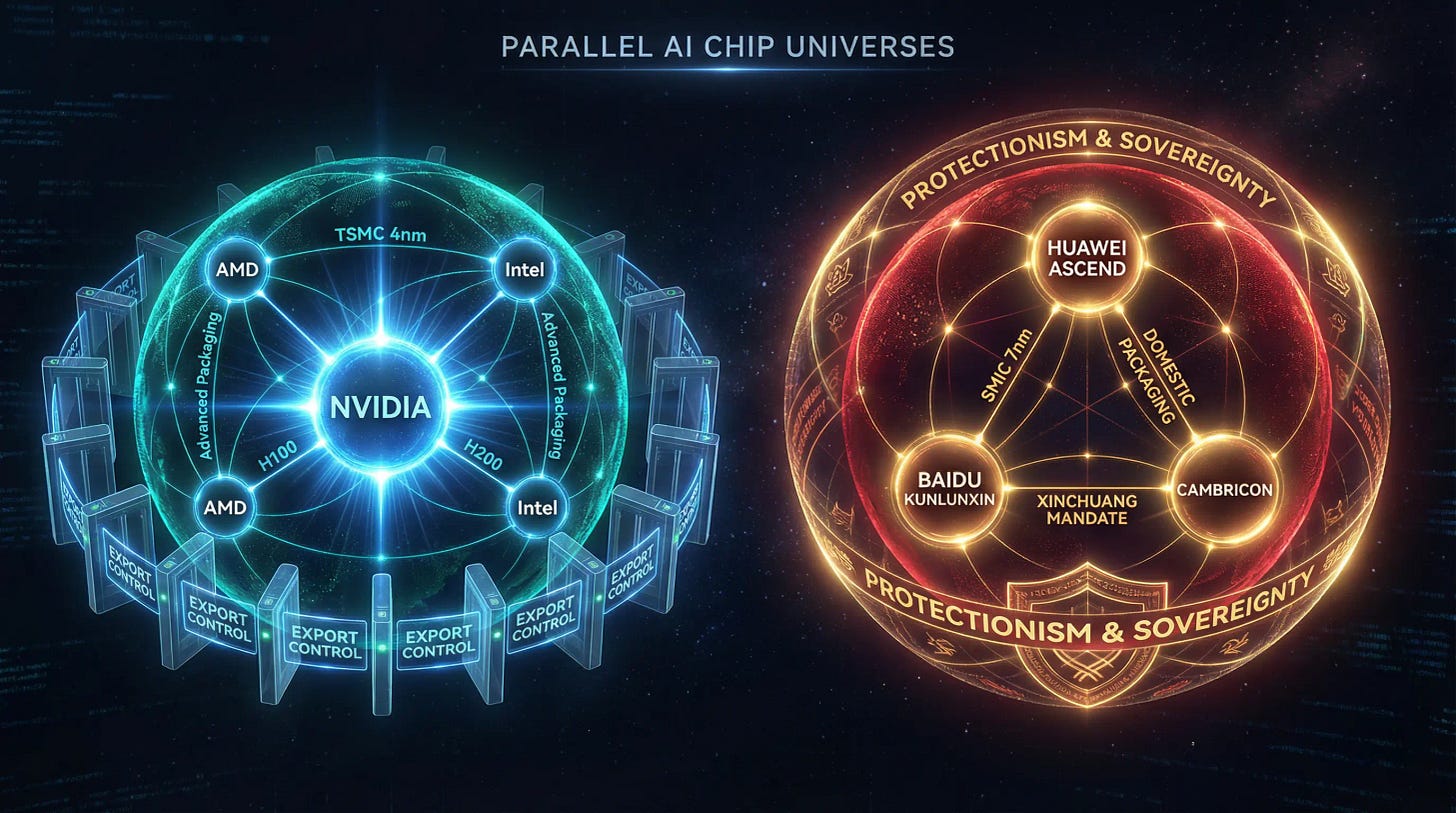

These three moves in one week were not coincidental. They reveal something more fundamental than Chinese industrial policy reacting to American restrictions. What we’re witnessing is reciprocal weaponization of market access to create segregated compute universes. Kunlunxin’s spin-off is precisely positioned for the moment this bifurcation becomes permanent.

How Access Became a Weapon

The coordination becomes clear when you examine what each side is actually doing.

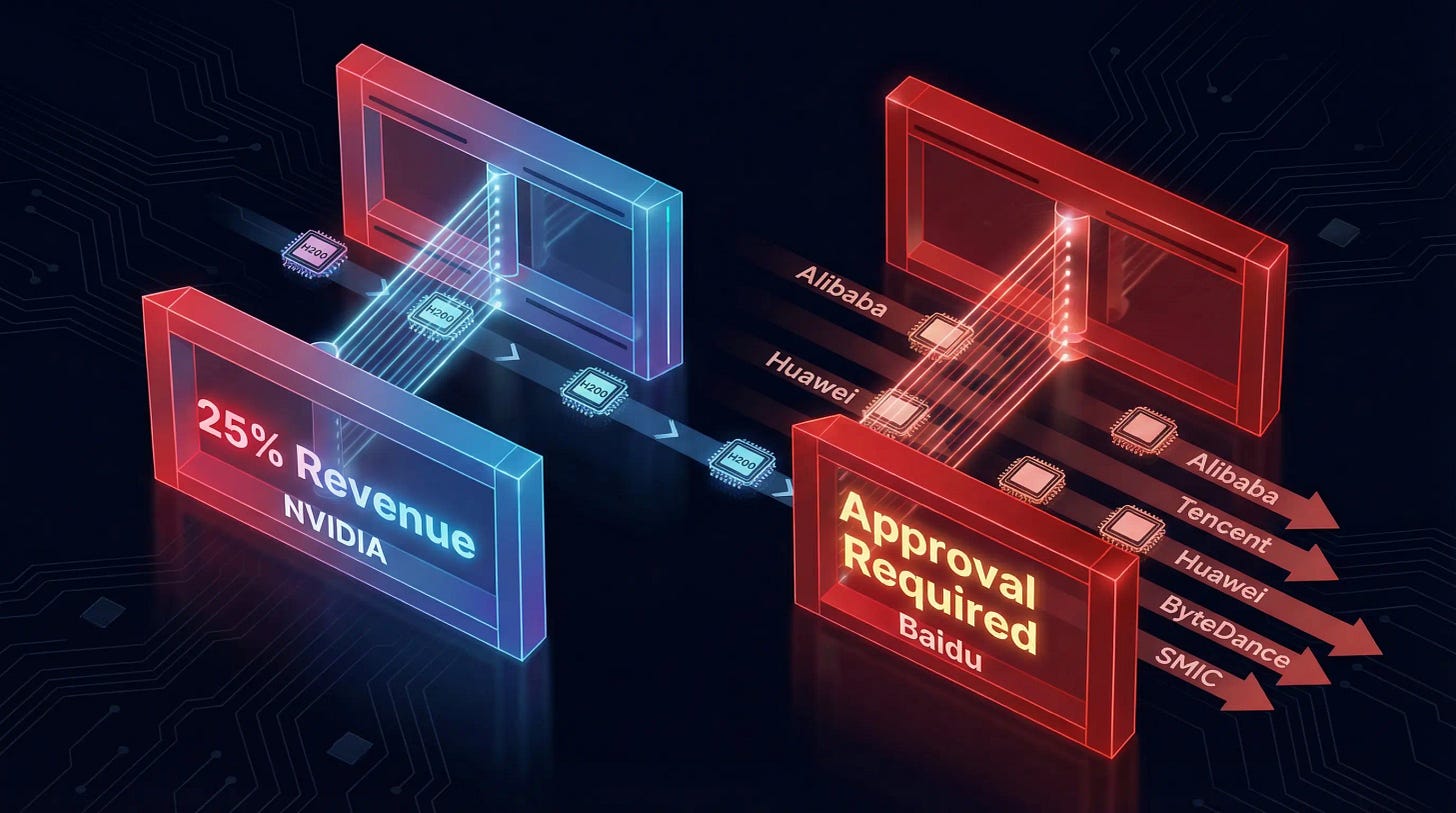

Washington is dangling access while demanding tribute. Trump’s H200 clearance comes with a 25% revenue requirement, though the legal mechanism remains unclear. David Sacks, the White House AI tsar, frames this as making Beijing reliant on US technology. But Congress sees it differently. A bipartisan group of senators introduced legislation to prevent H200 exports for 30 months. Democratic Senator Chris Coons called the decision “a colossal economic and national security failure” that would “squander America’s primary advantage in the AI race.”

Beijing is doing the mirror image. According to sources familiar with regulatory discussions, China will allow limited H200 access through an approval process. Buyers must submit requests explaining why domestic chips are inadequate. Previous behavior suggests the friction is deliberate. When Trump previously cleared the less advanced H20 chip for China, Beijing restricted tech companies’ access, saying its performance was “not significantly better than Chinese alternatives.”

The pattern is deliberate market segmentation. China will allow some H200 access for private tech giants like Alibaba, ByteDance, and Tencent. This serves as a pressure relief valve, preventing these companies from falling too far behind global competitors. But the vastly larger public sector faces different rules.

The Xinchuang procurement list (信创, literally “Information Technology Innovation”) makes this explicit. The list guides government agencies, public institutions, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) spending billions annually on IT products. AI chips from Huawei and Cambricon were added for the first time this year. The list mandates procurement rather than merely suggesting it.

The result is a two-tier market. The high-end private sector can access H200 through approval friction. The massive public sector becomes a captive market for domestic chips. Scale matters here. Beijing’s “East Data West Computing” initiative–an industrial policy routing coastal data processing to inland provinces where electricity is cheaper–channels billions in state investment. Government agencies, SOEs, and telecom operators dwarf private tech spending.

But this raises a critical question: if H200 does become available, even in limited quantities, how will Chinese companies actually use it? And more importantly, how much will they want to depend on a chip whose availability has proven so politically volatile? I explored this dynamic in detail–including which Chinese entities are likely to receive H200 allocations and for what specific workloads–in “What Does China Really Want From Nvidia’s H200?” The short answer: H200 will be used tactically for frontier research, but domestic chips will own the infrastructure layer.

Kunlunxin’s spin-off timing makes perfect sense in this context. To compete in the protected tier, the company needs distance from its parent. The transformation from “Baidu’s chip” to “China’s chip” requires more than corporate restructuring.

The Three Layers That Make Idle Chips Rational

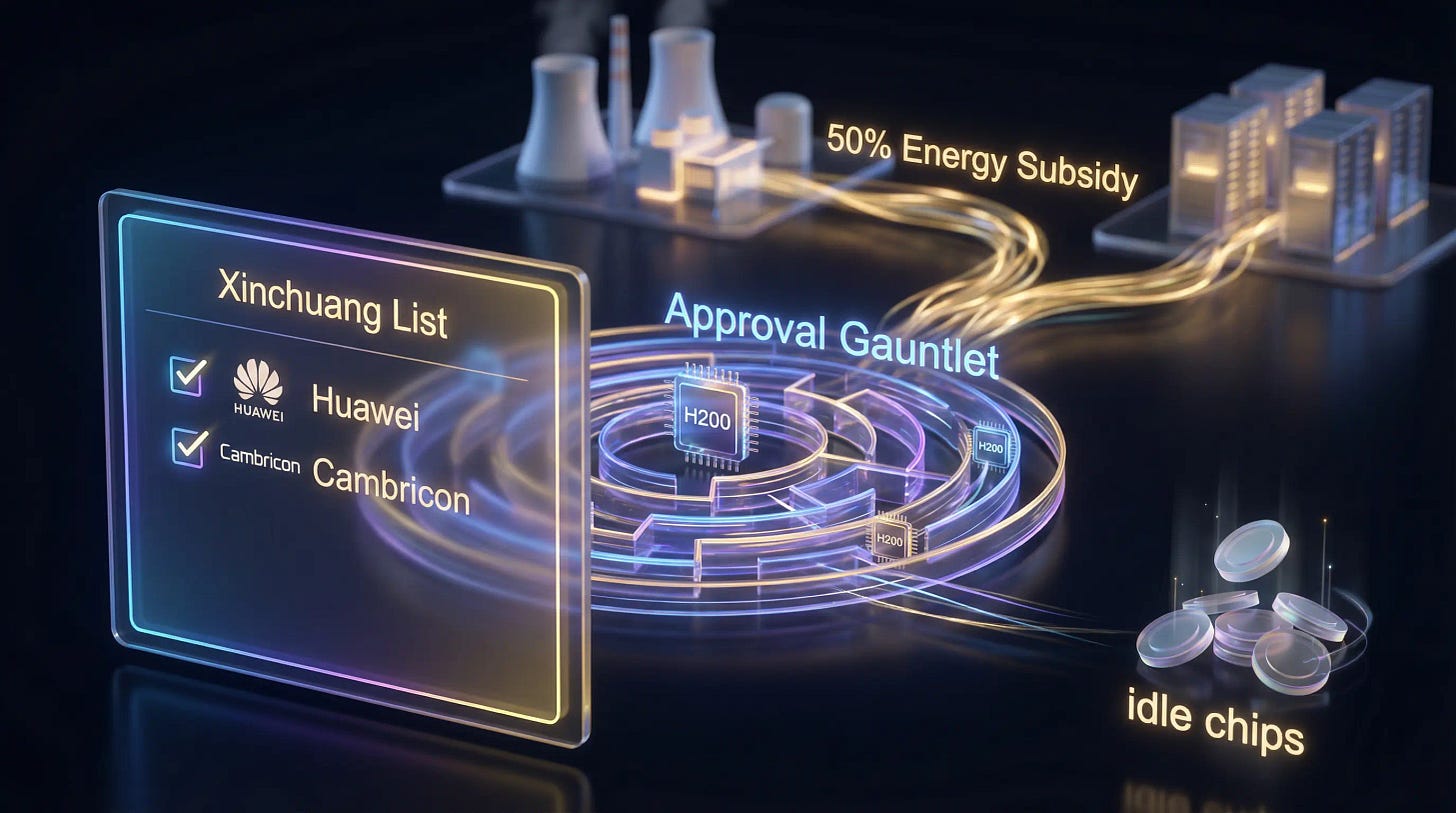

Here’s what the new market looks like in practice. A Chinese government-controlled investment firm spent $14 million on domestic AI chips, the Financial Times reported. The chips now sit unused. The firm’s quantitative trading algorithms were built for Nvidia hardware. Switching would mean rewriting code from scratch in an unfamiliar programming language.

The immediate interpretation: procurement failure. But viewed through market segmentation, these idle chips represent transition costs. A Chinese policymaker told the FT: “The growing pains are unavoidable. But we have to get there.”

Getting there means establishing parallel compute infrastructure. The idle chips are the price of building two separate markets.

Three layers make this structure work. The Xinchuang list forms the foundation. Think of it as combining FDA approval standards with Buy American mandates and security clearance requirements. Kunlunxin’s independence from Baidu becomes eligibility for this list.

The H200 approval gauntlet creates the second layer. Requiring companies to prove domestic inadequacy creates designed friction rather than regulatory caution. The paperwork burden makes choosing foreign chips more expensive than performance gaps alone would justify. This mirrors how EU’s GDPR compliance costs favor local cloud providers over American alternatives.

Energy subsidies form the third layer. China recently increased subsidies cutting electricity bills by up to 50% for data centers using domestic chips. This offsets the efficiency gap. Domestic semiconductors consume more power for the same workload. The subsidy makes “good enough plus subsidized” competitive with “better at full cost.”

Together, these layers create a market where Kunlunxin doesn’t need to beat H200 on performance. It needs three credentials: presence on the procurement list, status as the path of least paperwork, and qualification for energy subsidies. The spin-off is about meeting these requirements.

When Performance Stopped Mattering

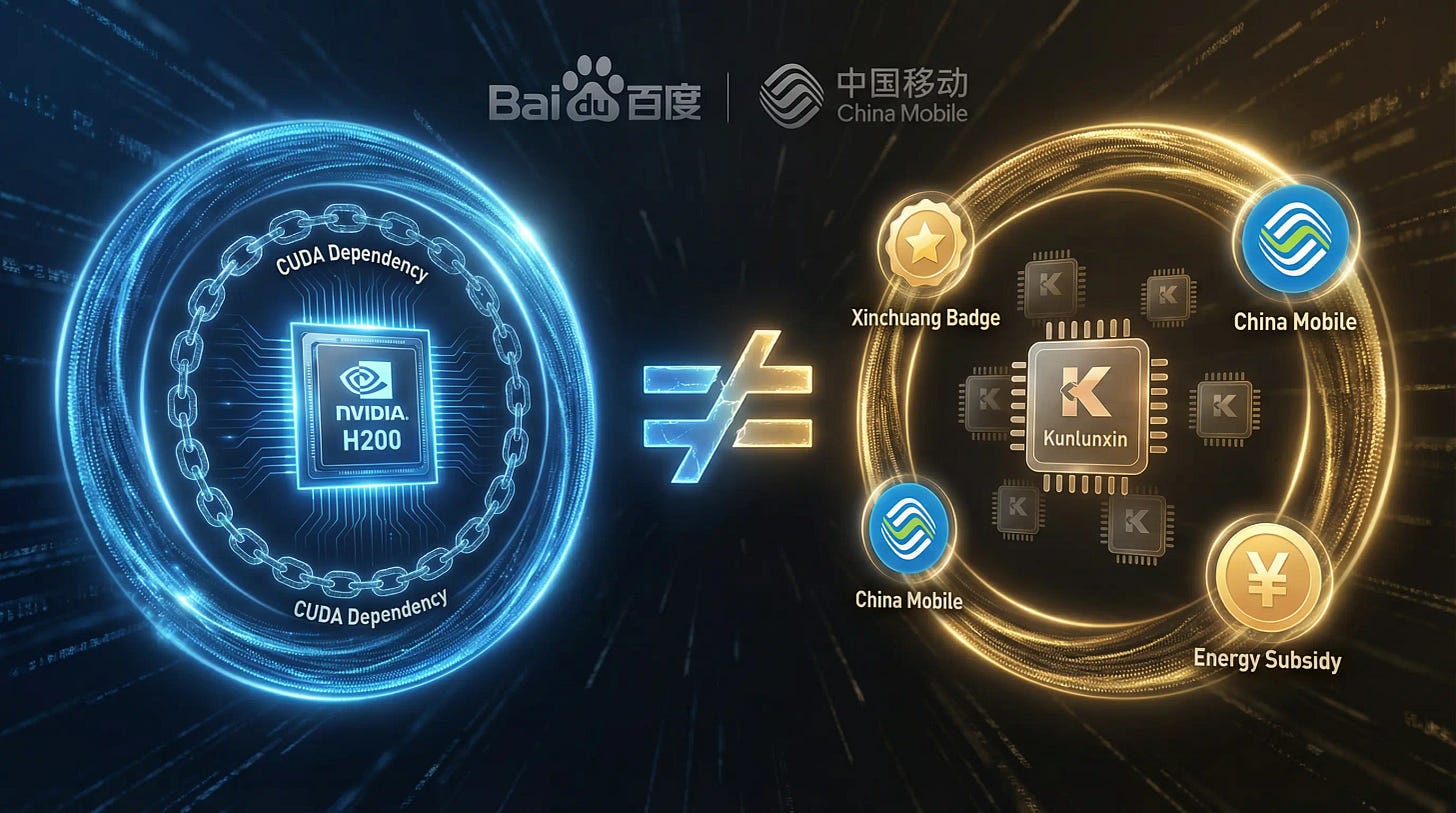

The capital structure reveals the protected market thesis. Kunlunxin’s investor roster includes market VCs like CPE and IDG, state capital through the National Talent Fund, strategic customer China Mobile’s industry fund, and industrial capital from BYD.

China Mobile’s dual role deserves attention. As an investor, the company has aligned interests in Kunlunxin’s success. As a customer, it controls billions in telecom infrastructure procurement. Both roles together create a credibility signal. If China Mobile trusts Kunlunxin, other SOEs can follow.

Baidu diluted its stake to 59% from over 70%. The dilution accomplishes what capital alone cannot: transforming “Baidu’s chip” into “China’s chip” in the eyes of government procurement officials. At 70% ownership, Kunlunxin reads as Baidu’s subsidiary. At 59% with China Mobile and state funds as co-investors, the company gains strategic repositioning beyond its parent’s identity.

Revenue composition confirms the strategy. Kunlunxin generated approximately 2 billion yuan in 2024 and is targeting over 3.5 billion yuan in 2025. External revenue now accounts for 40 to 50% of total sales. But composition matters more than percentage. According to market reports, virtually all external revenue comes from telecom operators and government sectors. Zero comes from other internet companies.

This reveals what China Mobile and similar customers are actually buying. They’re acquiring compliance tokens rather than selecting superior chips. The technical choices Kunlunxin made reinforce this interpretation.

The company uses a VLIW architecture instead of GPU design. This sacrifices compatibility with Nvidia’s CUDA software ecosystem, the industry standard. But CUDA compatibility means CUDA dependency. VLIW combined with PaddlePaddle–Baidu’s deep learning framework with 3 million developers, China’s alternative to TensorFlow–creates an independent software stack.

Memory architecture follows the same logic. Kunlunxin uses GDDR6 instead of high-bandwidth memory. HBM offers better performance but remains supply-constrained and sanctions-vulnerable. GDDR6 is commodity hardware, widely available and resilient to export controls.

Manufacturing tells the same story. Current generation chips use 7nm process technology, likely from SMIC’s domestic fabrication. This can’t match TSMC’s advanced 4nm process used in Nvidia’s chips. But SMIC’s process is sovereign.

Each technical choice prioritizes independence over excellence. This only makes sense if you believe three premises: markets will stay segregated through approval requirements, the protected market will be large enough to sustain the business, and subsidies will offset performance gaps. Kunlunxin’s roadmap bets all three are correct.

Whether those premises hold depends largely on how H200 actually gets deployed in China–a question that turns out to be more complex than “can they buy it?” As I detailed in my analysis of the H200 decision, China’s strategy appears to be treating H200 as a useful but unreliable resource whose availability depends on US politics. (Read the full analysis here) The implication for Kunlunxin: if H200 remains constrained to frontier labs and never reaches mass deployment, the protected market thesis strengthens.

The deployment of a 30,000-chip cluster validates scale readiness. Baidu announced this cluster can simultaneously support training multiple models with hundreds of billions of parameters and enable 1,000 enterprises to fine-tune models with tens of billions of parameters. The numbers matter less than the demonstration. Kunlunxin can handle hyperscale deployments, the credential that matters for East Data West Computing infrastructure projects.

Reading the Spin-off as a Signal

For Baidu shareholders, the spin-off represents a sum-of-parts unlock. Baidu trades at depressed multiples compared to peers. Spinning off Kunlunxin at a $3 billion valuation forces rerating of the parent company. It also reduces the capital expenditure drag from chip unit losses. Kunlunxin posted a net loss of approximately 200 million yuan in 2024 but is guiding for breakeven in 2025.

The risk: if the spin-off fails to secure listing on the procurement mandate, the entire thesis collapses. Without that credential, external revenue from mandatory procurement evaporates. The company reverts to being captive to Baidu with no valuation premium.

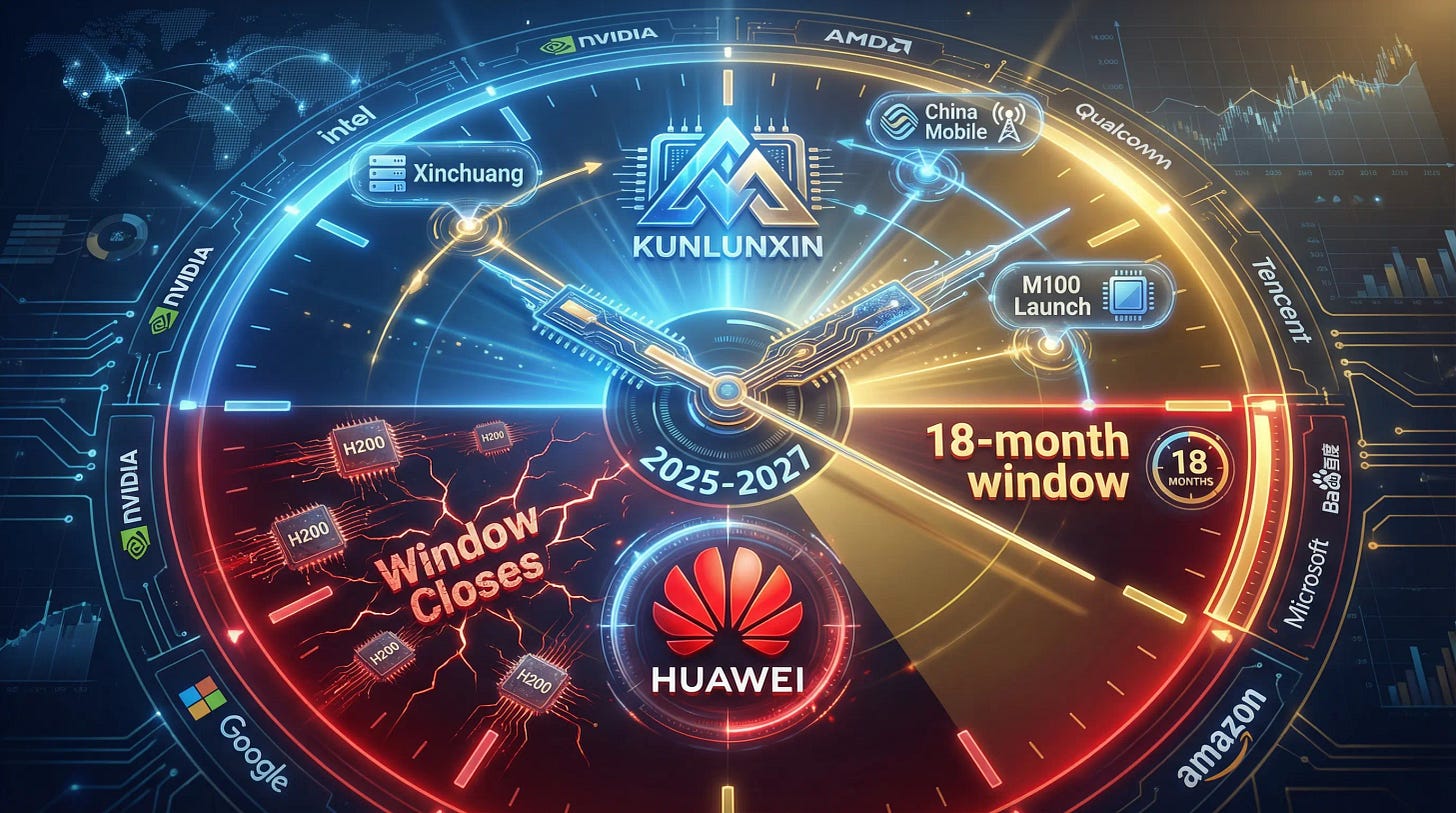

For potential IPO investors, this represents a timing play on market segmentation rather than a technology bet. The bull case depends on a specific 18-month window. H200 approval requirements create enough friction to keep the protected market protected. Kunlunxin secures listing on the Xinchuang mandate and replicates the China Mobile procurement model across other telecom operators, energy companies, and financial institutions. Energy subsidies remain in place, making performance gaps economically irrelevant. The M100 chip ships in 2026, providing an “improvement narrative” for the IPO roadshow.

If this sequence executes, revenue could scale from 2 billion yuan in 2024 to 3.5 billion in 2025 to potentially 6 to 8 billion yuan by 2026 as protected market procurement accelerates. A 3 to 4 times revenue multiple at IPO would support the $3 billion valuation.

One major variable in this thesis: how aggressively H200 penetrates Chinese cloud and inference workloads. If H200 floods the frontier tier but stays out of infrastructure, Kunlunxin’s protected market expands. If approval processes weaken and H200 reaches deeper into the stack, competition intensifies. The evidence so far suggests the former–Chinese regulators appear determined to limit H200 to tactical roles. (I break down Beijing’s likely allocation strategy and what it means for domestic chip demand here.)

The bear case sees the window close. Trump’s H200 clearance combines with failure of Beijing’s approval process to let Nvidia flood back. The performance gap proves too large even for mandatory buyers to accept. Huawei dominates the protected market, leaving Kunlunxin as a distant third option. The idle chips problem scales, creating public backlash over efficiency waste. The IPO window misses, leaving the unit stuck as a Baidu subsidiary.

The critical metric: percentage of external revenue from non-telecom, non-government buyers. Currently close to zero. If that number stays zero through 2026, Kunlunxin operates purely as a policy arbitrage play with no organic demand. If it rises above 20%, it signals genuine technical credibility beyond protected procurement.

For the broader tech industry, the implications extend beyond one company. We’re watching the establishment of a threshold for “good enough” sovereign compute. The combination of 7nm manufacturing, GDDR6 memory, and architectural innovation like VLIW proves adequate for most deployment scenarios. Only frontier model training requires cutting-edge hardware like H100 or H200. This creates sustainable basis for parallel markets.

Software vendors serving Chinese enterprise customers must now support both technology stacks. Maintaining CUDA and PaddlePaddle versions becomes like supporting iOS and Android. The cost is mandatory for market access.

The efficiency cost of segregation is substantial. Beijing accepts idle chips, 50% energy subsidies, and code rewriting expenses to achieve sovereignty. Washington fails to fully deny China advanced chips while also failing to maintain Chinese dependency. Both sides weaponize access. Neither achieves their stated goal. Instead, we get duplicated infrastructure, wasted resources, and slowed innovation.

The irony: companies positioned at the segmentation point, like Kunlunxin, become the real winners. They don’t need superior technology. They need the right credentials at the right time.

The New Equilibrium

When Baidu announced its evaluation of the Kunlunxin spin-off, Trump cleared H200 exports, and Beijing formalized domestic chip mandates in the same week, these weren’t three separate events. They marked the crystallization of a new equilibrium: two parallel compute universes, each with distinct rules, technologies, and economics.

Kunlunxin’s bet is straightforward. The protected universe–comprising China’s public sector, telecom operators, and government-controlled enterprises–is large enough, subsidized enough, and policy-protected enough to sustain a multi-billion dollar chip company that doesn’t need to beat Nvidia. It just needs to be the right kind of Chinese.

The idle chips sitting in that government-controlled investment firm aren’t system bugs. They represent the system working as designed. Each idle chip represents a calculated trade: small efficiency sacrifice for large sovereignty gain. Multiply that across every government agency, SOE, and telecom operator, and you have a market worth tens of billions.

The real test: will China’s segregated market structure persist long enough for Kunlunxin to establish itself as the independent option? Not Baidu’s chip. Not Huawei’s chip. China’s chip.

Based on coordinated policy timing, deliberate capital structure, and careful technical roadmap, Baidu is betting yes. The timing of H200 clearance proves that even when barriers fall, Beijing can reconstruct them differently. The era of globally unified compute infrastructure is over. We’re entering the age of credentialed computing. Kunlunxin’s spin-off is the IPO prospectus for that new reality.

Related Reading

This analysis examines why China’s AI chip market is shifting toward credential-based allocation. For a deeper look at how H200 fits into this new structure–including which Chinese entities will likely receive allocations, what workloads they’ll use them for, and why Beijing is unlikely to build long-term capacity planning around US chips–read:

Available to premium subscribers

Thanks so much for this analysis - it is super helpful. Quick question regarding where you got the information for the specs. You mentioned that Kunlunxin uses a VLIW architecture instead of GPU design, GDDR7 instead of 7nm, and SMIC 7nm manufacturing. I thought Samsung was Baidu's foundry partner but, I could be wrong. I have found it difficult to find specs on the P800.

The idle chips framing is genius because it flips the conventional wisdom on waste. When people see $14M sitting unused they assume dysfunction, but the three-layer structure you mapped shows it's actually strategic patience. I ran into similiar dynamics working with overseas expansion teams where compliance costs can dwarf efficency losses short-term. One thing worth tracking is whether non-telecom external revenue breaks 20% becuase that's when we'll know if the market actually wants sovereign compute or just needs it.