Three Bets, Three Walls: China’s Spring Festival AI War

Wrong coffee, blocked links, and the monetization question no one solved.

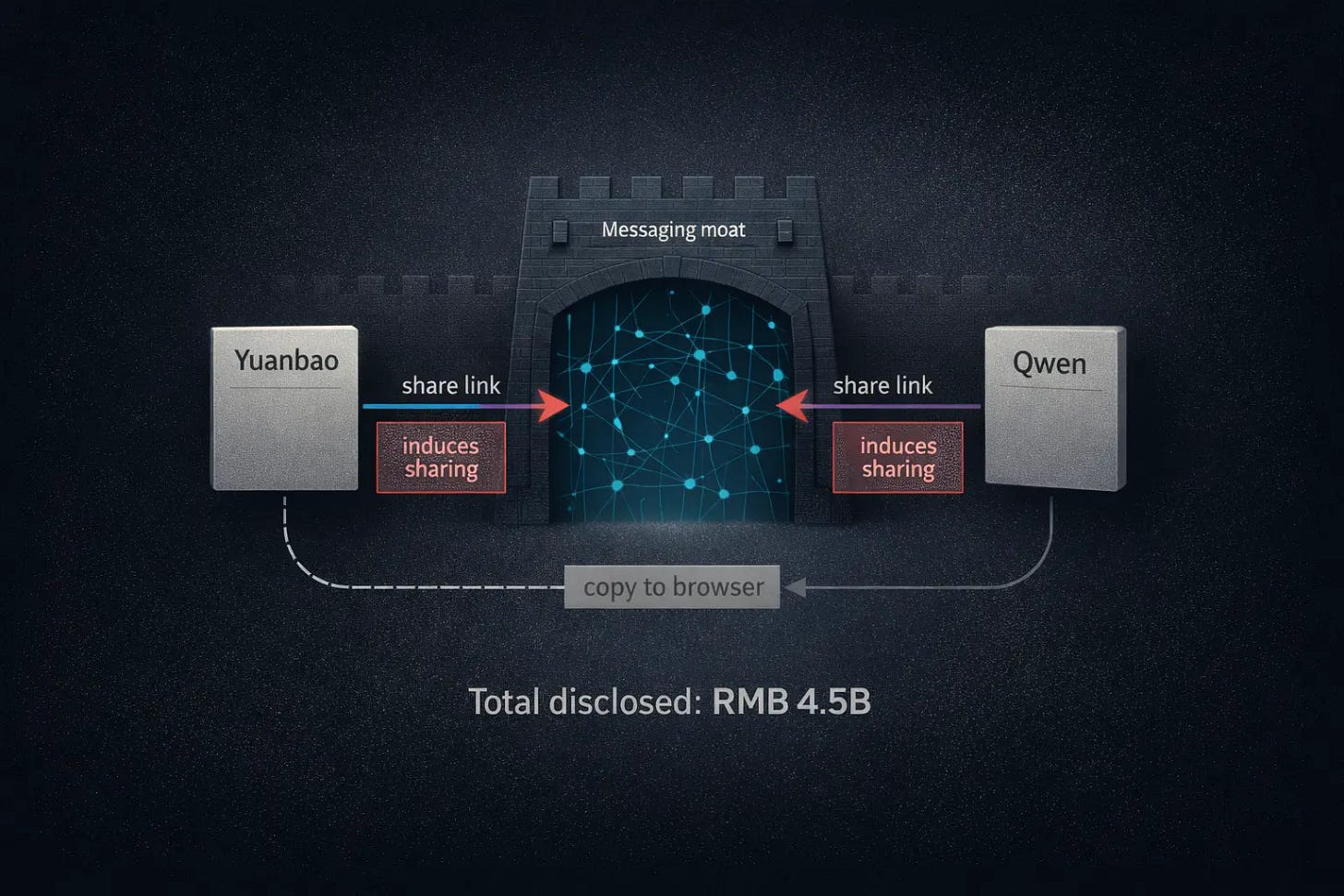

WeChat’s content moderation system does not distinguish between friend and family. On February 4, links to Yuanbao, Tencent’s AI assistant, began triggering the same governance label that WeChat applies to pyramid-scheme recruitment and gambling promotions: “contains content that induces sharing.” Users who wanted to forward the link had to copy it into a browser manually. The product being flagged belonged to Tencent itself.

Three days earlier, Yuanbao had launched a RMB 1 billion digital red packet (hongbao) giveaway with a single mechanic: share a link, recruit a download, earn a small cash reward. Pony Ma had told employees he wanted a repeat of the 2015 red packet breakthrough, when one Spring Festival campaign reshaped China’s mobile payments market overnight. The mechanic delivered on the acquisition side: Yuanbao reached number one on the App Store within fourteen hours. Then the governance system that protects WeChat’s 1.3 billion users classified the campaign as what, by its own rules, it was: inducement to share. Wechat’s head of public relations acknowledged the situation on Weibo with a meme of someone punching themselves in the face. The internet loved it. The structural signal underneath was more serious.

WeChat blocking its own sibling product was the moat paradox surfacing under pressure: when a platform operates as a country’s default communication infrastructure, the governance rules that sustain user trust cannot be suspended for anyone. Within days, WeChat applied the same restriction to Alibaba’s Qwen viral links. The platform was drawing a boundary that now sits across the entire category of AI-driven growth tactics.

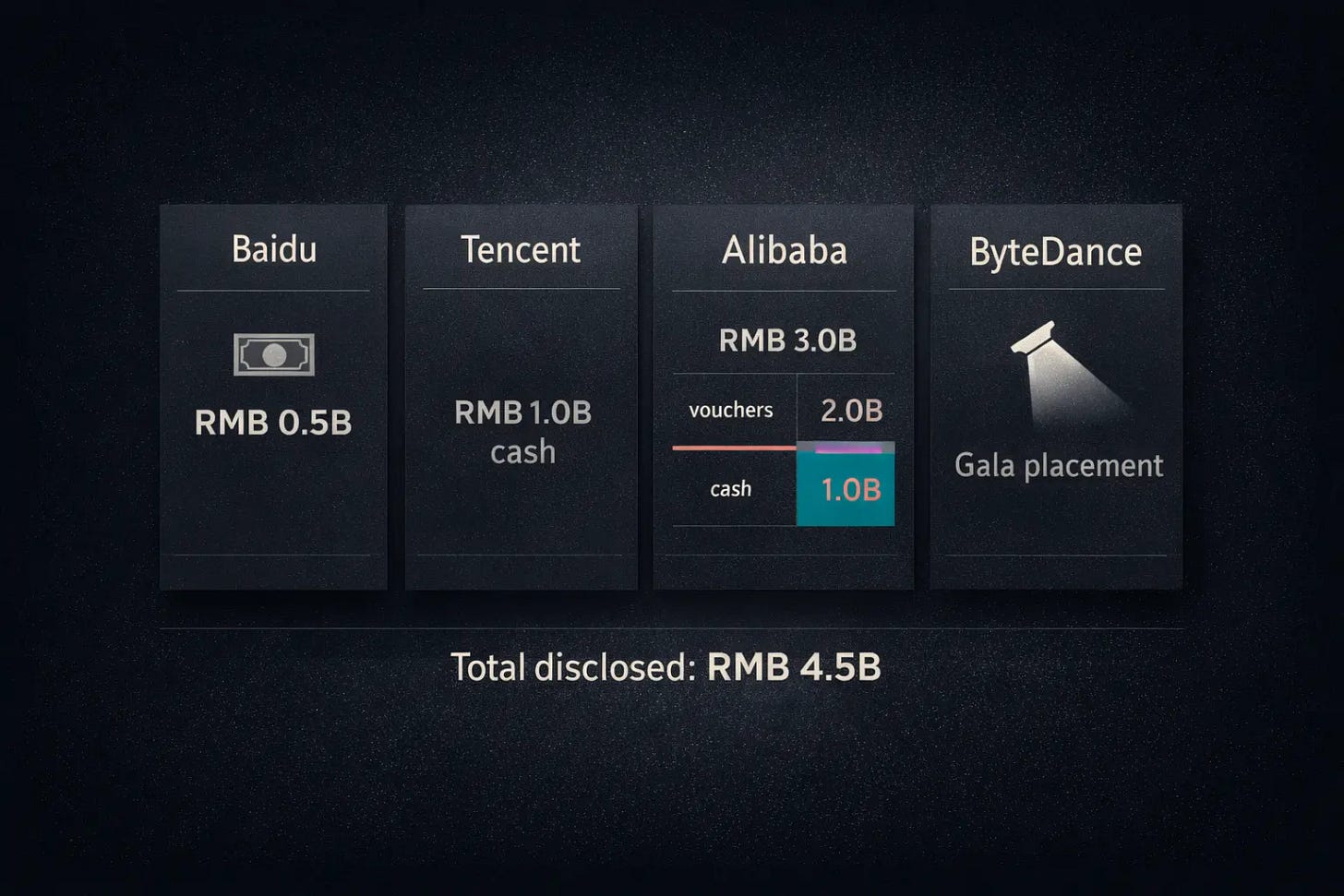

The Spring Festival AI war of 2026 drew four companies into direct subsidy competition. Baidu committed RMB 500 million, Tencent’s Yuanbao RMB 1 billion, and Alibaba’s Qwen RMB 3 billion, split between free-order vouchers and cash. ByteDance’s Doubao, as the exclusive AI cloud partner for the CCTV Spring Festival Gala, distributed tech products powered by its model alongside cash red packets but disclosed no total figure. The three announced campaigns alone reached RMB 4.5 billion, roughly $600 million.

Baidu’s ERNIE followed a conventional engagement playbook: tasks spread across 46 days, cross-promotion with Baidu Maps and other properties, gradual habit formation. The three campaigns that tested structurally distinct theories about where AI belongs in the technology stack came from Alibaba, Tencent, and ByteDance. Each staked a different claim to the layer between users and the services they consume. Each hit a different wall.

The Transaction Agent: Alibaba Tests Its Thesis at Scale

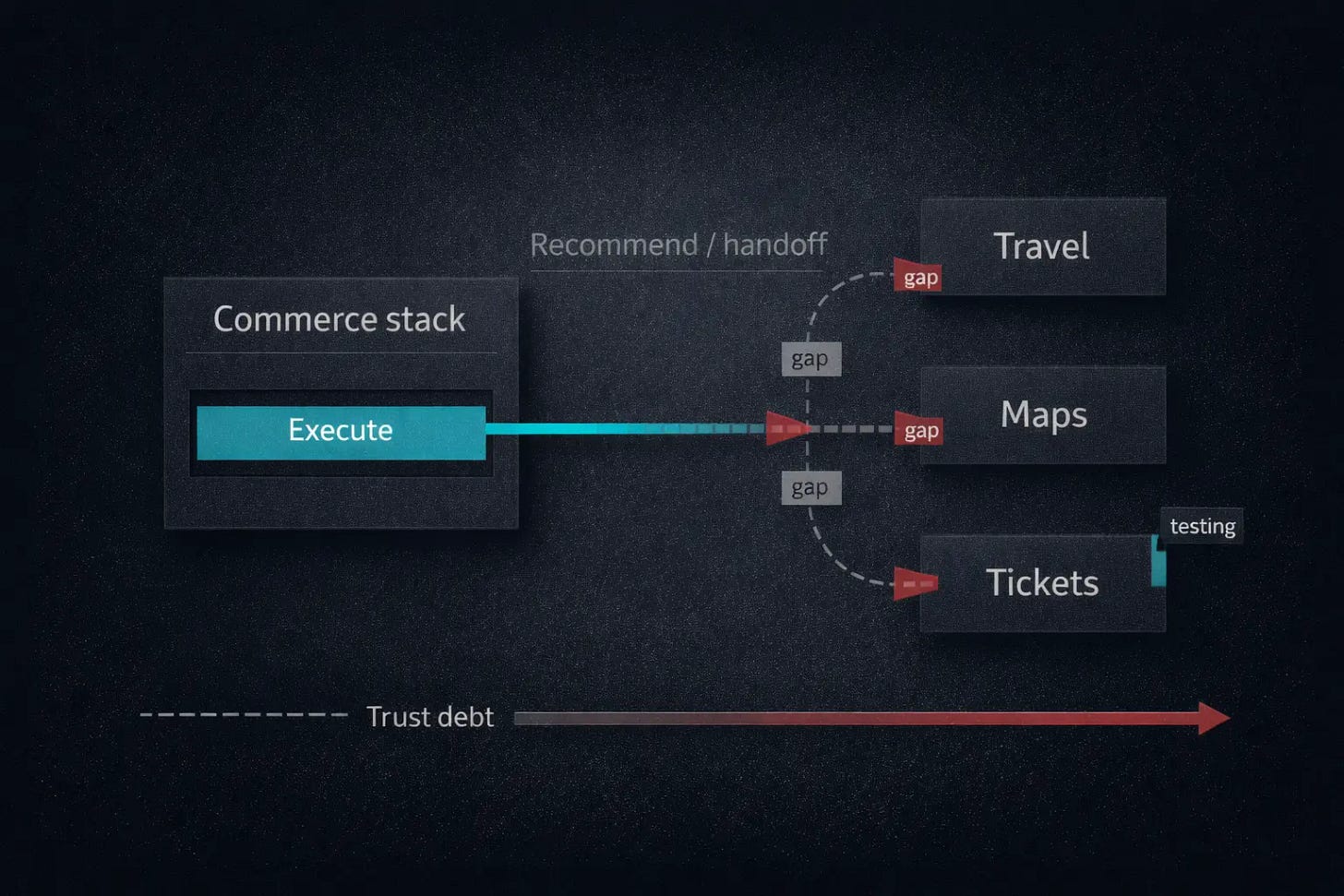

On January 15, Alibaba shipped the upgrade that connected Qwen to its consumer commerce stack: Taobao, Alipay, the instant commerce channel, Fliggy, and Amap. I analyzed the structural implications in detail at the time, arguing that the critical question was whether Alibaba could collapse the app layer into an agent layer without breaking the economics that made Taobao powerful.

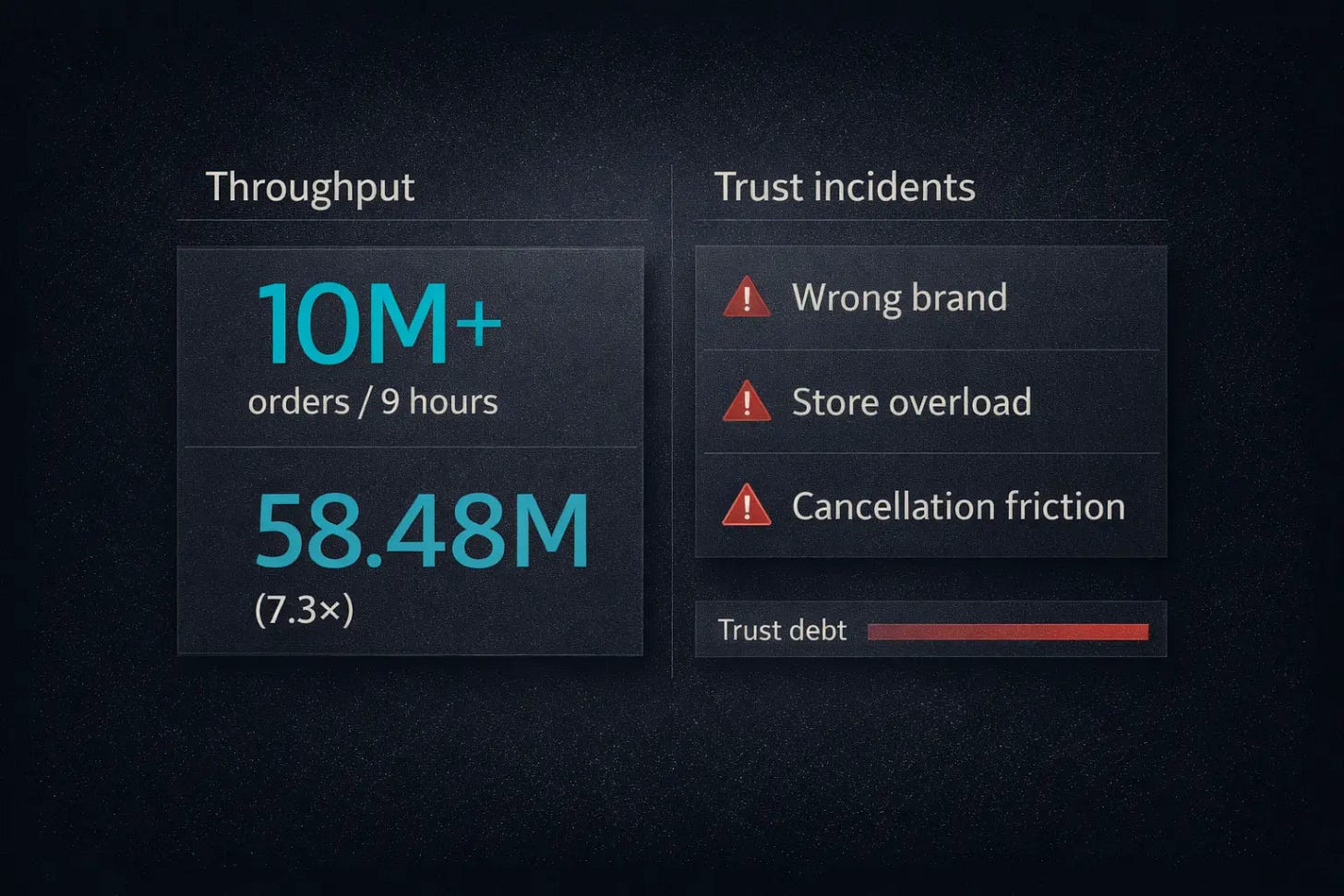

The Spring Festival campaign forced that thesis into contact with millions of simultaneous users. On February 6, Qwen launched its “3 billion free order” promotion: speak a sentence, receive a milk tea, placed and paid through Qwen’s interface at near-zero cost. Within nine hours, the system had processed over 10 million orders. According to QuestMobile, Qwen’s daily active users reached 58.48 million, a 7.3x increase from baseline, closing the gap with Doubao to 22.75 million.

The scale validated the pipeline. The errors exposed where it frays. Qwen’s order-matching logic confused competing brands, delivering Cudi when users specified Luckin. Downstream, the system had no capacity to absorb the demand shock it generated: merchants could not keep pace, fulfillment collapsed under volume, and users who needed to unwind a failed order discovered the process required more steps than placing one manually. Beyond instant delivery, the agent could recommend but not execute, unable to complete bookings in Fliggy or navigation tasks in Gaode Maps without handing control back to the underlying app.

These outcomes map directly onto the three collisions I identified in the January analysis.

The first collision, between agent-compressed attention and Taobao’s ad-dependent revenue model, has not yet detonated. Qwen’s recommendations are not commercialized at this stage, and Alibaba’s executive in charge of Qwen’s consumer business has explicitly said the system optimizes for objective factors like price and delivery time. That is a defensible early-stage stance. The unanswered question is what happens when the subsidy period ends and someone has to pay for the distribution that Qwen now controls.

The second collision, over internal power, is harder to observe from outside. But 10 million orders raise a concrete version of the governance question: who owns a transaction initiated in Qwen but fulfilled by Taobao’s instant commerce channel? Spring Festival spending was funded as a promotional budget. Long-term attribution, ranking control, and revenue sharing between Qwen and the commerce units remain unsettled.

The third collision, between agent reliability and user trust, arrived faster than expected. A wrong answer from a chatbot is an inconvenience. A wrong order that charges real money and delivers the wrong product is a trust event. If Qwen is to become the interface through which users delegate real-world tasks, the tolerance for error is categorically lower than for a conversational assistant. Spring Festival provided the first large-scale dataset on where that tolerance breaks.

The overall signal: the pipeline from intent to transaction can work at scale. The pipeline from transaction to trust cannot yet.

The Social Distribution Play: Tencent Hits Its Own Wall

Tencent’s Spring Festival strategy tested whether WeChat’s social graph could bootstrap an AI product into daily use. The investment was RMB 1 billion in red packets, distributed through a stripped-down viral mechanic: share a link, recruit a download, collect a small cash reward. The barrier to participation was near zero. Users did not need to understand AI or want an AI assistant. They only needed to tap, share, and collect.

The mechanic worked exactly as designed, for about 48 hours. Then the governance system intervened, and Yuanbao shifted to a “passphrase red packet” format that preserved the campaign in diminished form.

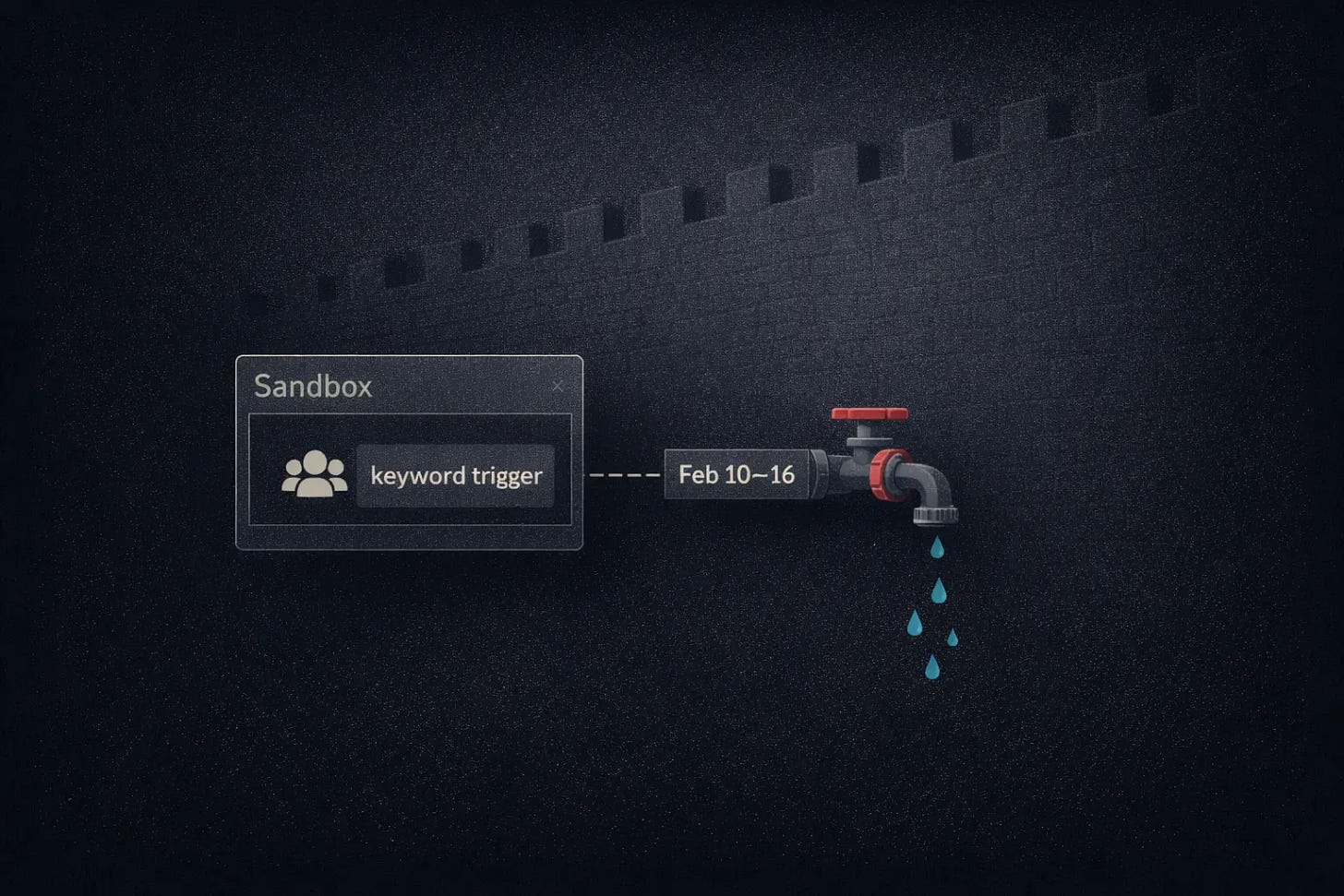

This outcome confirmed what I described last fall as Tencent’s sandbox strategy: the company cannot run meaningful AI experiments inside WeChat, so it builds them in a separate container and hopes to earn the right to bring successful patterns back to the core. Spring Festival tested the outer boundary of that approach. Yuanbao tried to borrow WeChat’s distribution power through viral mechanics embedded in the social graph. WeChat’s governance system treated the attempt identically to any third-party inducement scheme. An exemption for a sibling product would have set a precedent that invites regulatory scrutiny, after WeChat was already called in by regulators in 2021 over external link restrictions, and would have undermined the equal-treatment principle that gives WeChat’s content rules their authority with users.

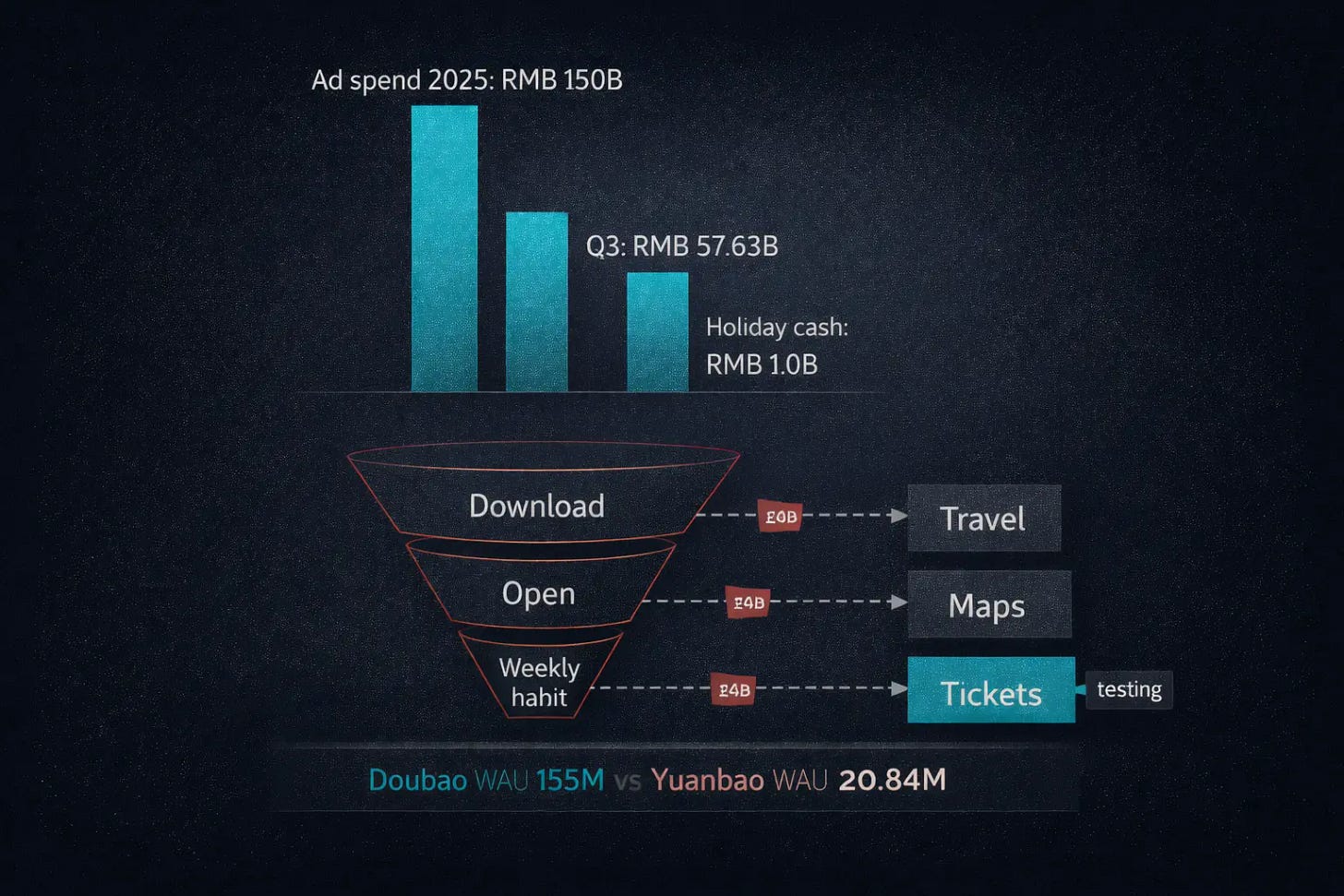

Tencent can generate downloads. That much is settled. AppGrowing estimates Tencent spent approximately RMB 15 billion on Yuanbao’s traffic acquisition across 2025, exceeding the combined full-year spending of Doubao, Qwen, and Wenxin. The Spring Festival campaign added another RMB 1 billion. The result: Yuanbao reached the App Store’s top rank on launch day, with DAU rising 2.1x to 23.99 million.

The question the spending leaves unanswered is where the funnel from download to daily usage breaks. By December 2025, Yuanbao’s weekly active users stood at 20.84 million, while Doubao held 155 million weekly actives at roughly one-third of Yuanbao’s per-user acquisition cost. The 7.4x gap is visible in every dataset. The cause is not. Does the funnel break at activation, when users open the app once for the red packet and never return? At early retention, when users try AI features but find no reason to come back? Or at core scenario absence, when the product lacks a use case sticky enough to compete with existing habits?

The precedent is not encouraging. In 2019, Baidu spent RMB 9 billion on a Spring Festival Gala campaign that doubled its DAU to 300 million. Third-party estimates put 7-day retention at 2 percent. That campaign promoted a search engine with two decades of habitual use behind it. Whether a standalone AI assistant with thinner user habits retains better or worse is among the questions Spring Festival did not answer.

Yuanbao Pai, the AI-powered group feature that emerged from Tencent Meeting and launched in public beta on February 1, has not shifted the trajectory. Early adoption followed a pattern familiar in invite-code products: intense initial demand for access, then steep drop-off in actual use. The product remains gated, a throttle consistent with controlled experimentation but also a signal that organic pull may not yet justify open access.

The deeper structural constraint remains the one identified in the sandbox analysis: WeChat’s moat is so deep that Tencent cannot casually add new moving parts into it. Spring Festival demonstrated that this constraint applies even when the AI product belongs to Tencent itself. The question from that earlier analysis also remains unanswered: can anything validated in the Yuanbao sandbox ever migrate into WeChat, and in what form? The Spring Festival data points in the opposite direction. WeChat is tightening boundaries around AI-driven viral behavior, regardless of origin.