Moonshot AI’s $1.4 Billion War Chest: Buying the Right to Say No

Moonshot’s $500M raise bought one thing: the option to skip the traffic war and fund the compute race on its own terms.

December 2025 revealed a divide in China’s AI startup landscape.

Zhipu AI filed its Hong Kong IPO prospectus on December 19. MiniMax followed on December 21. Both companies disclosed healthy unit economics and rapid revenue growth. Both were running out of cash. Zhipu held RMB 2.55 billion in reserves with monthly burn approaching RMB 300 million. MiniMax had roughly RMB 7.35 billion but burned through RMB 2 billion monthly. The IPO timing was necessity, not choice.

Ten days later, Moonshot AI announced a $500 million Series C. The round brought total cash reserves to over RMB 10 billion, roughly $1.4 billion. Founder Yang Zhilin sent an internal memo. The core message was direct: “We’re not in a rush to go public.”

Moonshot had more cash than Zhipu and MiniMax combined. What mattered was what that money enabled. For companies racing toward IPO, cash is fuel for a competition they can’t afford to lose. For Moonshot, it became the freedom to exit a race it couldn’t win.

The Traffic Trap: Why Big Tech’s Playbook Kills Startups

Chinese AI startups face a brutal choice. Follow Big Tech’s traffic acquisition strategy, or find another path entirely. The first option looks obvious. Build a consumer app. Buy users through aggressive marketing. Scale fast before competitors do. Every Chinese internet company since 2010 has done this.

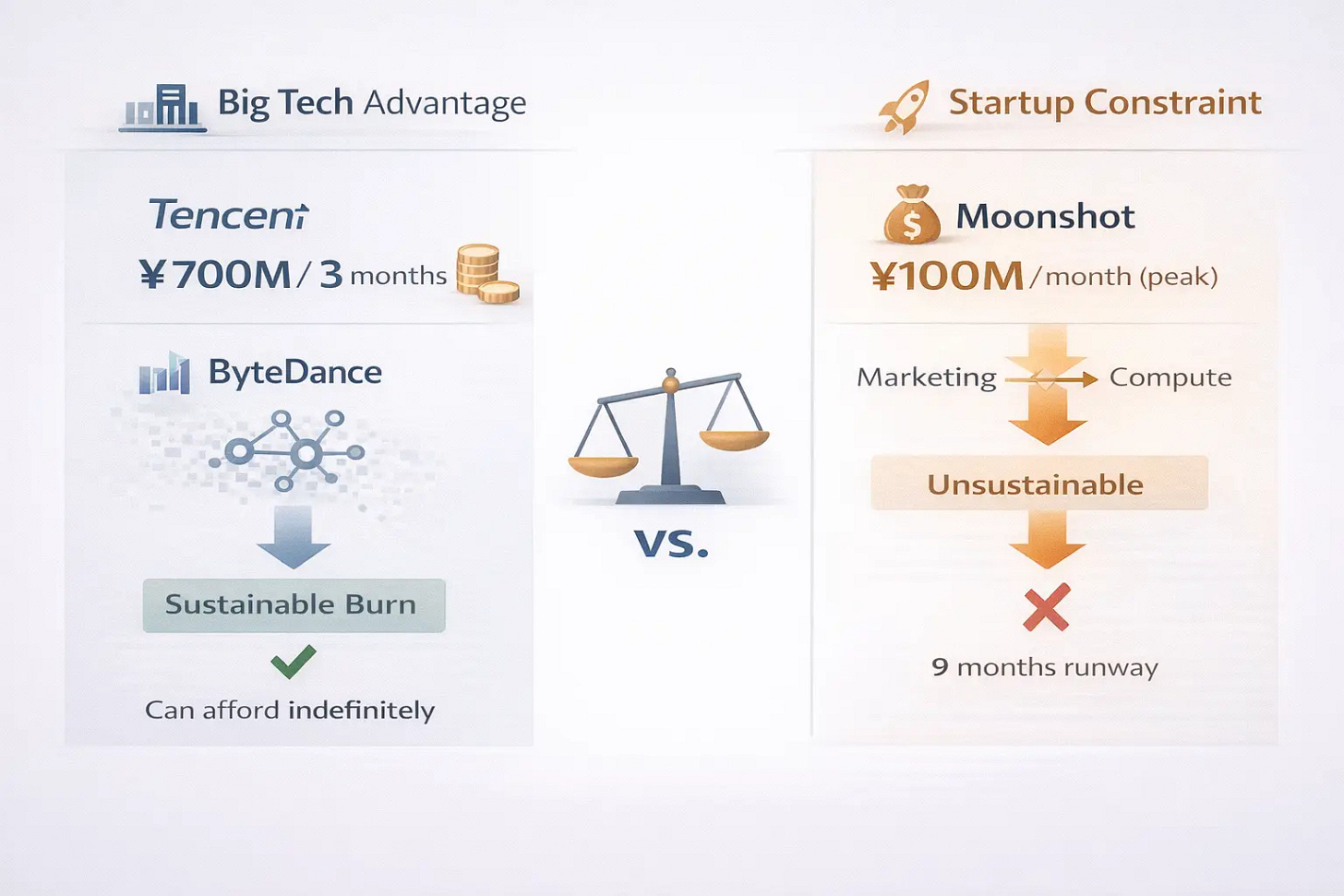

The economics are straightforward. Tencent spent over RMB 700 million in three months marketing Yuanbao, its AI assistant. ByteDance’s Doubao leveraged distribution advantage by blocking external AI apps from advertising on Douyin and other ByteDance properties. Alibaba deployed a multi-product strategy across Qwen App, Quark, Lingguang, and Afu.

The math is simple for Big Tech. They own distribution. They control compute infrastructure. They generate cash from other businesses. A RMB 2 billion annual loss is a rounding error in consolidated statements. They treat AI as strategic investment with no quarterly profit pressure.

Startups can’t match this. They can’t outspend platforms with infinite capital. They can’t out-distribute companies that own the channels. They can’t sustain burn rates when every yuan spent on user acquisition is a yuan not spent on model training. The fundamental problem runs deeper than capital. Traffic acquisition creates the wrong kind of growth. Users acquired through ads are expensive and fickle. Monthly active users become vanity metrics that mask unsustainable unit economics.

This creates a structural trap that forced Zhipu and MiniMax toward emergency IPOs in December. Both companies achieved healthy gross margins at the unit level. Zhipu maintained 56% gross margins. MiniMax’s B2B segment hit 69.4%. Both still burned through cash 5x faster than the market grew because competitive pressure forced compute investments that dwarfed revenue growth. My December analysistraced how this dynamic turns healthy unit economics into company-level cash crises.

The compute arms race doesn’t care about your business model. Whether you choose scale like Zhipu or efficiency like MiniMax, once a competitor forces another iteration, you must match the investment or become obsolete. Strategic differentiation becomes irrelevant when competition dictates behavior.

This is the structural trap. Healthy unit economics don’t prevent company-level cash crises. Strong gross margins don’t stop the burn when compute costs compound faster than revenue. The real challenge: affording to keep building good models quarter after quarter as the bar keeps rising.

From Buying Traffic to Earning Trust

Moonshot’s leadership saw this pattern forming in early 2025. The insight was simpler than it sounds: you can’t win a traffic war and a compute war simultaneously.

Big Tech wins traffic acquisition because they own distribution and can sustain infinite burn. Startups lose because they’re renting both the distribution and the compute. The capital requirements compound. Every yuan spent on user acquisition is a yuan not spent on model training. Every iteration cycle forced by competition drains reserves that marketing campaigns already depleted.

But there’s a different acquisition channel. Instead of buying users through ads, earn them through demonstrated capability. Instead of competing for consumer attention on ByteDance’s platforms, compete for developer mindshare on GitHub and OpenRouter. Let customers discover you through benchmark performance, not sales teams.

This requires reallocating capital. Stop spending on user acquisition. Redirect everything to technical capability and proof points. Open-source your weights to build credibility. Publish academic papers to demonstrate competence. Let the product sell itself through reproducible results.

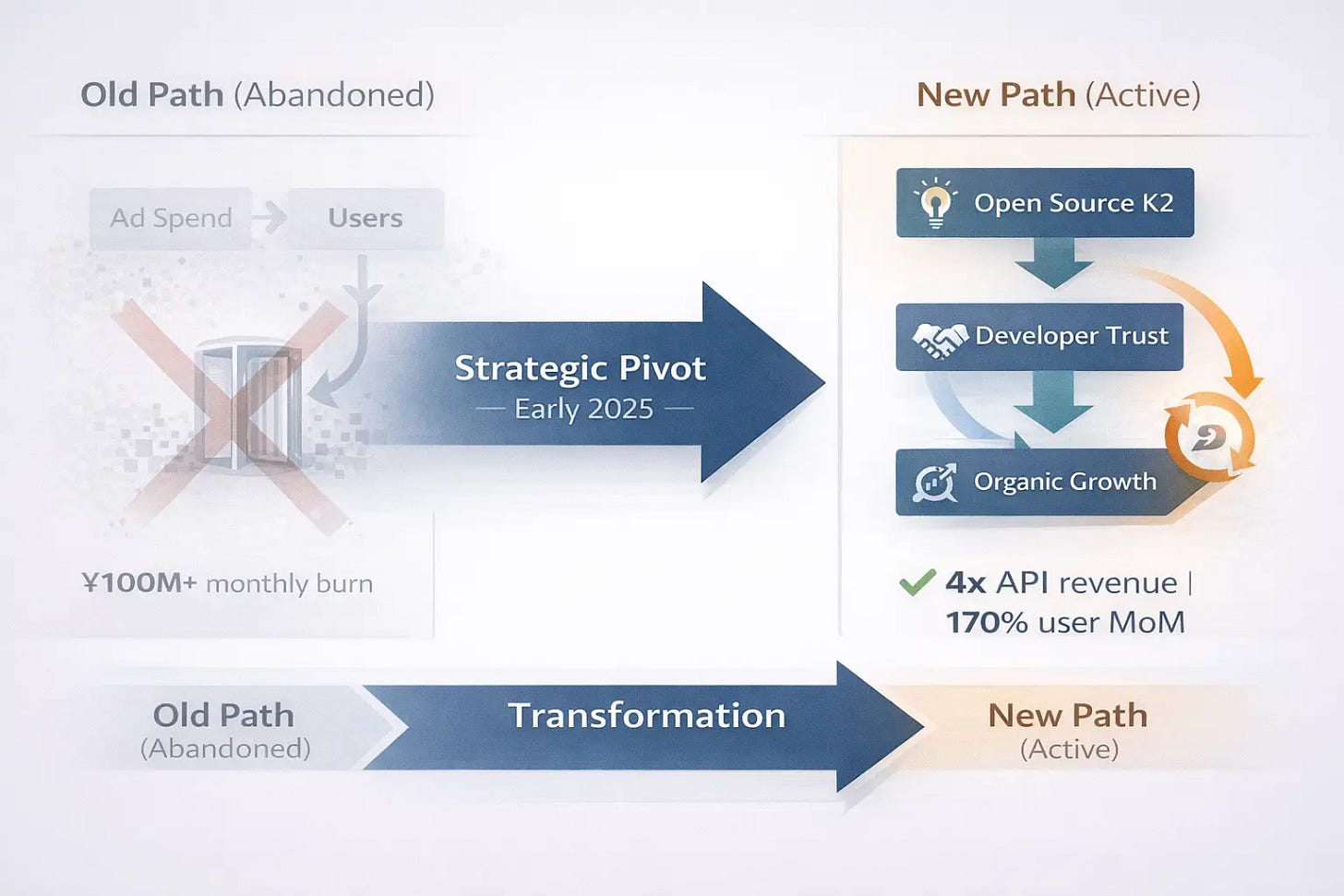

DeepSeek’s R1 launch in early 2025 validated this approach. The model proved that technical capability could drive adoption without marketing spend. Moonshot went all-in on the same bet. The company stopped all marketing spend. It killed multiple consumer products (Ohai, Noisee). It pivoted from closed-source to open-source. The algorithm team treated the shift as existential.

The strategy meant accepting three outcomes that looked like failures by conventional startup metrics.

Three Paradoxes That Reveal the New Logic

Paradox one: Marketing spend dropped to zero. Revenue growth accelerated. Moonshot’s overseas API revenue grew 4x from September to November 2025. Paying users grew over 170% month-over-month, both domestic and overseas. The company didn’t buy this growth through ads or sales teams. It earned it through technical performance.

The mechanism is straightforward. In July, Moonshot open-sourced the K2 model. Within a week, it hit #2 on OpenRouter’s global trending models. Developers tested it. They found the model competitive with Claude 4 Sonnet and GPT-4o variants on many benchmarks, but at dramatically lower API costs. Word spread through technical communities on Reddit, Hacker News, and GitHub.

This developer adoption drove commercial adoption. B2B customers don’t buy AI services because of TikTok ads. They buy based on technical evaluations, API reliability, and cost-performance ratios. Moonshot’s reputation as the cost-performance leader in global developer communities translated directly to API revenue. The product sold itself.

Paradox two: Open-sourcing the model created commercial value. This contradicts basic IP strategy. If you give away your core technology, what do you sell? The answer: inference at scale.

Moonshot released K2’s weights (1 trillion total parameters, 32 billion activated) for anyone to download and run. This seemed like giving away the crown jewels. But open weights served a specific strategic purpose. They let developers evaluate the model without committing to a paid API. They built trust and reputation. They demonstrated technical credibility.

The November release of K2 Thinking sharpened this strategy. The model scored 44.9% on Humanity’s Last Exam and 99.1% on AIME 2025 math problems with tool use. These aren’t marketing claims. They’re reproducible benchmarks that developers can verify themselves. Global AI communities described the release as the democratization of reasoning capability.

Chinese developers and international developers responded differently, but both validated the approach. Domestic users saw K2 as proof that Chinese AI companies could match frontier capabilities. International users saw it as a viable alternative to expensive Western APIs. Both groups became paying customers.

Paradox three: Raising $500 million created freedom to avoid IPO. Normally, late-stage funding creates pressure to exit. Investors want liquidity. The company needs to show returns. The path to IPO accelerates.

Yang’s internal memo flipped this logic. The RMB 10 billion+ cash position meant the company could handle 18–24 months of compute inflation without worrying about quarterly earnings or public market pressures. The money wasn’t fuel for aggressive expansion. It was insurance against being forced into the wrong strategic choices.

This matters because the next phase of Moonshot’s strategy is capital-intensive and long-term. Yang outlined the 2026 priorities: increase effective compute by at least one order of magnitude for the K3 model. Match frontier models at the pretraining level. Vertically integrate model training with agent product development. None of these goals optimize for short-term revenue or user growth.

The memo made this explicit: “We will not target absolute user numbers.” Instead, the company will focus on maximum capability and measurable productivity gains. This represents a fundamental rejection of consumer internet metrics. What matters is building AI systems that deliver measurable impact to professional users willing to pay for genuine productivity gains.

Cash makes this choice possible. Competitors rushing toward IPO cannot afford multi-year R&D bets that don’t show immediate returns. They need to demonstrate growth trajectories that satisfy public market expectations. Moonshot can take the longer view.

What This Reveals About AI Startup Strategy

Moonshot’s path suggests three broader patterns about how AI startups can compete.

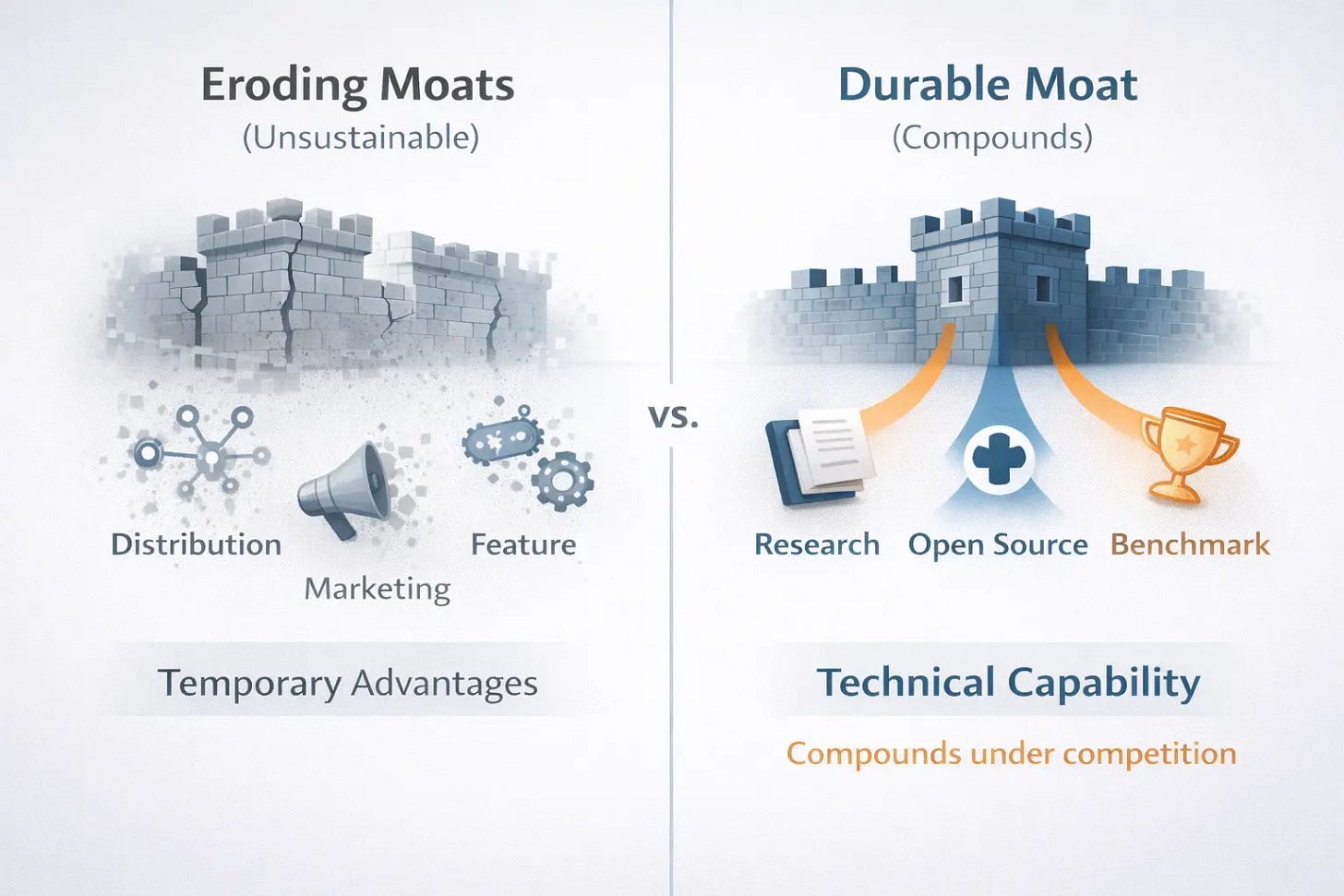

First, technical capability is becoming the scarcest moat under China’s competitive dynamics.Distribution advantages erode when platforms weaponize access. Marketing spend creates temporary spikes that don’t compound. Even large language model capabilities commoditize over time as open-source alternatives improve. But sustained investment in frontier research creates differentiation that’s harder for competitors to replicate at equivalent cost.

This explains why Moonshot invested heavily in academic outputs alongside commercial products. The company published papers on the Mooncake architecture (a KVCache-centric disaggregated system that increased long-context throughput by 525%) and linear attention mechanisms. These aren’t PR stunts. They’re proof of deep technical competence that builds credibility with sophisticated buyers.

The challenge is that technical capability takes time and capital to build. Most startups cannot afford 18–24 month research cycles with uncertain commercial outcomes. They need to show revenue growth to raise the next round. This creates pressure to optimize for near-term metrics rather than long-term capability building.

Second, open source can be a commercial strategy when compute costs collapse but capability still matters. This wasn’t true five years ago. Running large models was prohibitively expensive for most users. Today, efficient architectures like Mixture of Experts make it viable to offer high-capability models at low prices. Moonshot’s K2 has 1 trillion total parameters but only activates 32 billion per token. This gives it knowledge capacity approaching GPT-4 while maintaining inference costs closer to medium-sized models.

In this environment, open weights become a customer acquisition channel. Developers can verify claims themselves. They can run evaluations on their own benchmarks. They can build confidence before committing to paid APIs. The commercial value comes from managed inference, not model secrecy.

This only works if you can maintain technical leadership. Once your open model becomes commodity, you’re competing purely on price and infrastructure. Moonshot’s bet is that continuous research investment will keep it at the frontier. Whether this proves sustainable when facing the same competitive pressures that forced matching investments at Zhipu and MiniMax remains an open question.

Third, the lesson here centers on resource allocation rather than absolute capital. Moonshot used its war chest to exit one race (traffic acquisition) so it could compete in another (technical capability). This only works if you have enough runway to survive the transition period between stopping marketing and achieving organic growth through technical reputation.

The counterfactual reveals the constraint. Without sufficient capital, companies face forced choices. They must compete for users or die trying, even when that competition drains resources needed for technical development. They must optimize for short-term metrics that public markets demand, even when long-term capability building requires patient capital.

The Unanswered Question: Does This Strategy Scale?

But does Moonshot’s strategy escape the structural trap, or just delay it?

The K3 roadmap calls for increasing effective compute by 10x. That’s an enormous capital commitment. It’s also the same arms race that’s consuming Zhipu and MiniMax, just fought with different priorities and a larger war chest.

December’s dual IPO filings revealed how even dramatically different strategies converged on the same outcome. One company bet on frontier scale, the other on capital efficiency. Both ran out of runway as competitive pressure forced matching investments regardless of chosen path. Zhipu spent 26x more on R&D from 2022 to 2024. MiniMax optimized to 1% of OpenAI’s compute costs. Neither efficiency nor scale prevented the cash consumption spiral.

When DeepSeek forces the next iteration cycle, can Moonshot afford to keep matching without eventually facing the same pressure? The company has more runway than competitors. Whether it has enough runway for the market to grow into the burn rate is unproven.

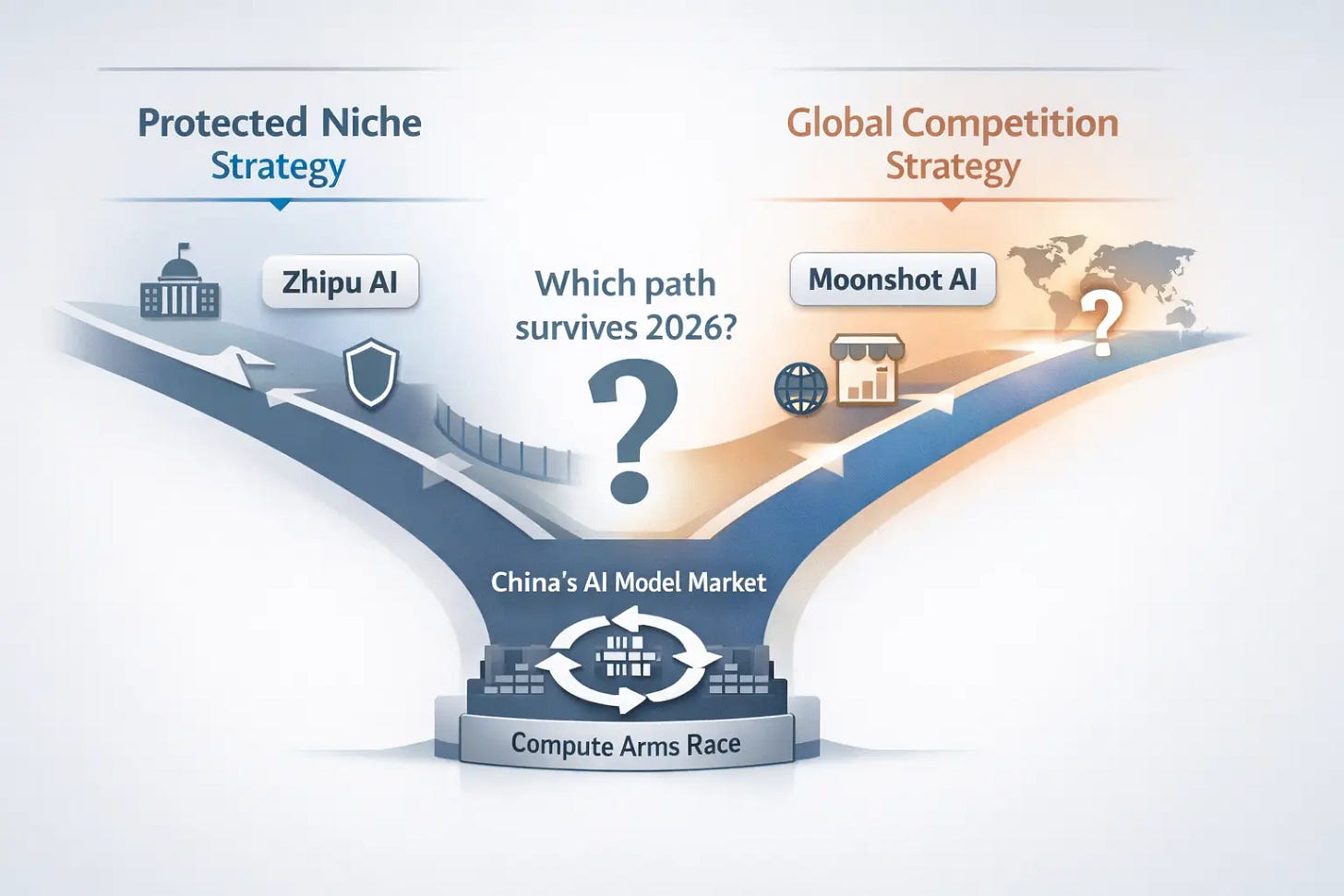

My October 2025 analysis I wrote on Zhipu’s transformation showed one escape route: find a protected market niche where political alignment matters more than pure technical competition. Zhipu pivoted to state-backed AI services, leveraging privileged access to government contracts that value institutional trust as much as capability. This creates a genuine moat in China’s political economy.

Moonshot is betting on a different path: that sustained technical leadership in global markets can create defensible differentiation. The company is deliberately avoiding protected domestic niches in favor of open global competition on technical merit. This is the harder bet. It requires maintaining frontier capabilities indefinitely. It requires converting technical superiority into sustainable commercial advantages before the next competitor forces another investment cycle.

Who Wins, Who Struggles

The strategic divide in China’s AI startup landscape is becoming clearer.

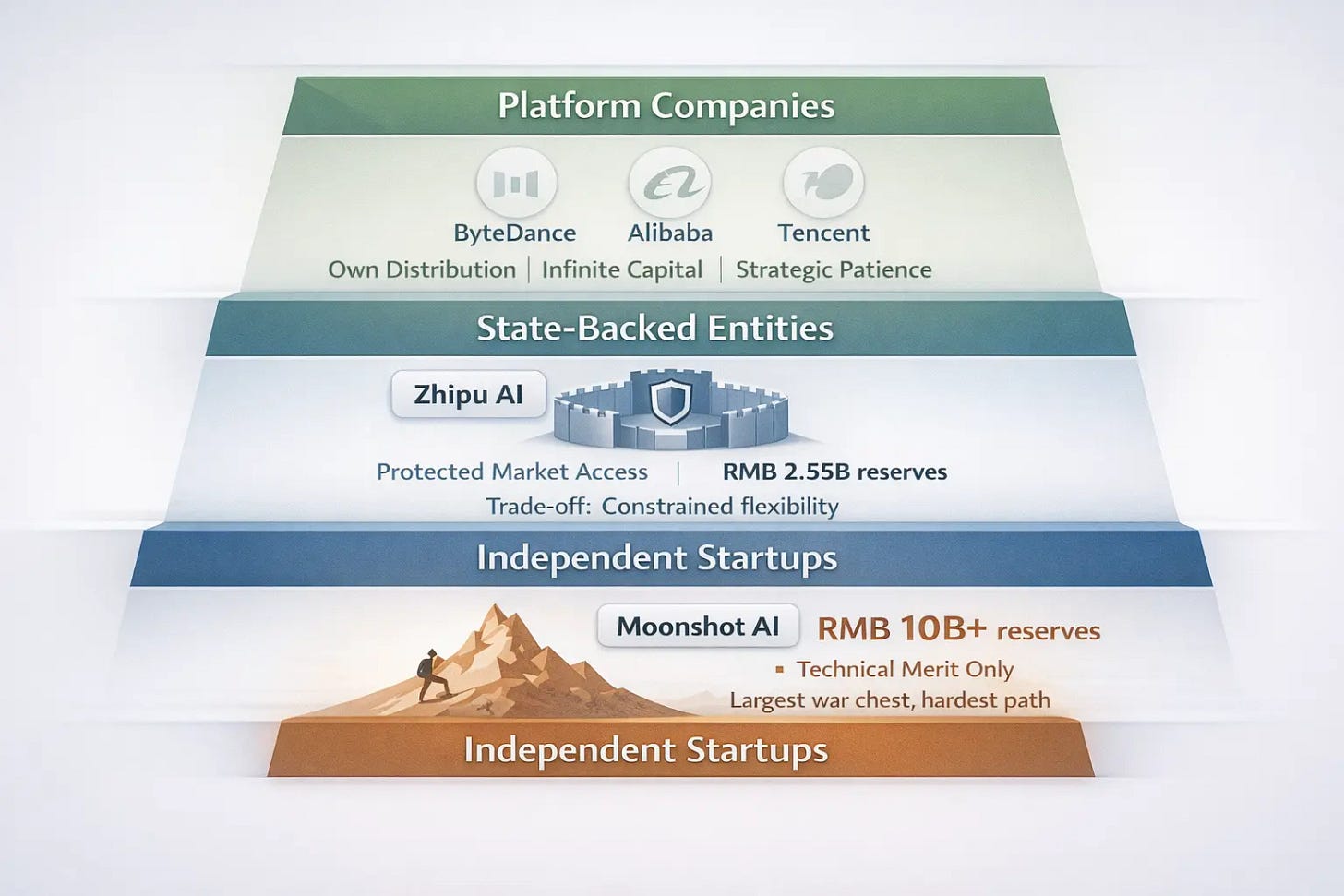

Platform companies (ByteDance, Alibaba, Tencent) maintain structural advantages. They own distribution. They control compute infrastructure. They can sustain losses indefinitely. They treat AI as strategic investment with no quarterly profit pressure. They’re playing a different game with different success metrics.

State-backed entities like Zhipu occupy protected niches. Government procurement and data sovereignty requirements create genuine moats that private tech giants can’t penetrate. The trade-off is accepting constraints on business model flexibility and international expansion. Success means becoming indispensable to state clients rather than maximizing shareholder returns.

Independent model companies face the hardest path. They must compete on technical merit without platform distribution or protected markets. Success requires exceptional execution on two dimensions simultaneously: building frontier capabilities and converting technical leadership into sustainable commercial advantages before capital runs out.

Moonshot’s $1.4 billion war chest buys more time than any independent competitor has. The bet is that technical leadership in global markets creates a different dynamic than competing for domestic market share. Whether this proves sufficient when facing the same structural forces that pushed Zhipu and MiniMax toward emergency IPOs is the question that will define 2026.

The answer depends on whether Moonshot can maintain technical differentiation faster than competitors can force matching investments. Whether global markets value that differentiation enough to justify the compute costs. Whether 18–24 months of runway is enough time for the strategy to validate.

These are open questions. The strategic clarity is real. The execution is impressive. But China’s AI market has a pattern of burning capital faster than it generates revenue, and competitive dynamics that force investments regardless of chosen strategy.

The Real Test Begins Now

Moonshot AI’s $500 million raise bought breathing room and optionality. The company used it to exit the traffic acquisition trap and bet everything on technical capability driving organic growth. The early results validate the approach. Whether the approach survives sustained competitive pressure from better-funded platforms and state-backed competitors is what 2026 will reveal.

The cash bought the freedom to choose. Whether that freedom translates to sustainable competitive advantage depends on execution that no Chinese AI startup has yet demonstrated: converting technical leadership into durable commercial moats while staying ahead of the compute arms race.

Time will tell if breathing room is enough.