Running Out of Runway

Two Chinese AI unicorns burn through cash 5x faster than the market grows. Their December IPO filings reveal the desperation.

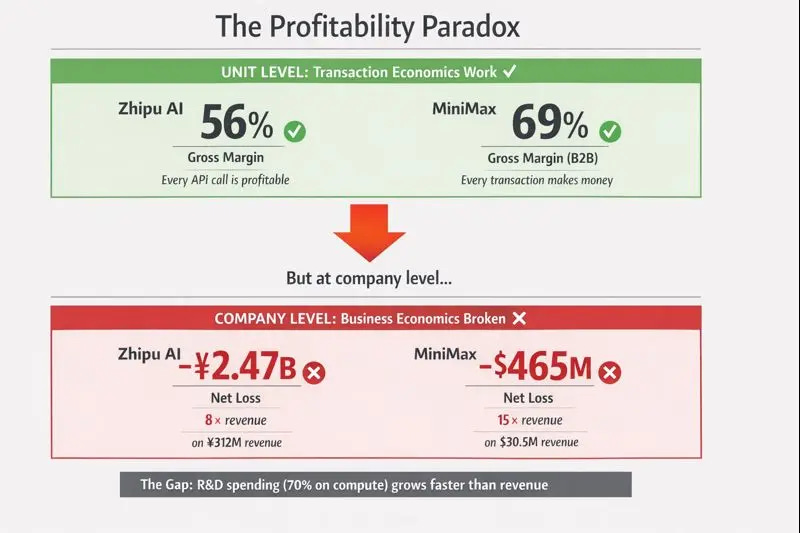

Gross margins of 56% and 69%. Revenue growth of 130% and 782%. Months of cash left.

Last week’s dual IPO filings from Zhipu AI and MiniMax reveal a paradox at the heart of China’s AI model market. Both companies have proven they can build competitive technology. Both have validated their business models at the unit economics level. Both are running out of time.

Zhipu, backed by Tsinghua University, passed its Hong Kong listing hearing on December 16 and disclosed its prospectus on December 19. MiniMax, a Shanghai-based startup founded in 2021, followed with its hearing on December 17 and prospectus on December 21. The synchronized timing reveals shared desperation.

The numbers tell the story. Zhipu grew from ¥57 million in 2022 to ¥312 million in 2024, a 130% compound annual growth rate. MiniMax achieved even more dramatic expansion, with revenue surging 782% to $30.5 million in 2024. In the first nine months of 2025, MiniMax generated $53.4 million, already exceeding its full-year 2024 results.

But losses grew faster. Zhipu’s adjusted net loss exploded from ¥97 million in 2022 to ¥2.47 billion in 2024. That’s 20x growth. MiniMax went from $7.37 million in losses in 2022 to $465 million in 2024.

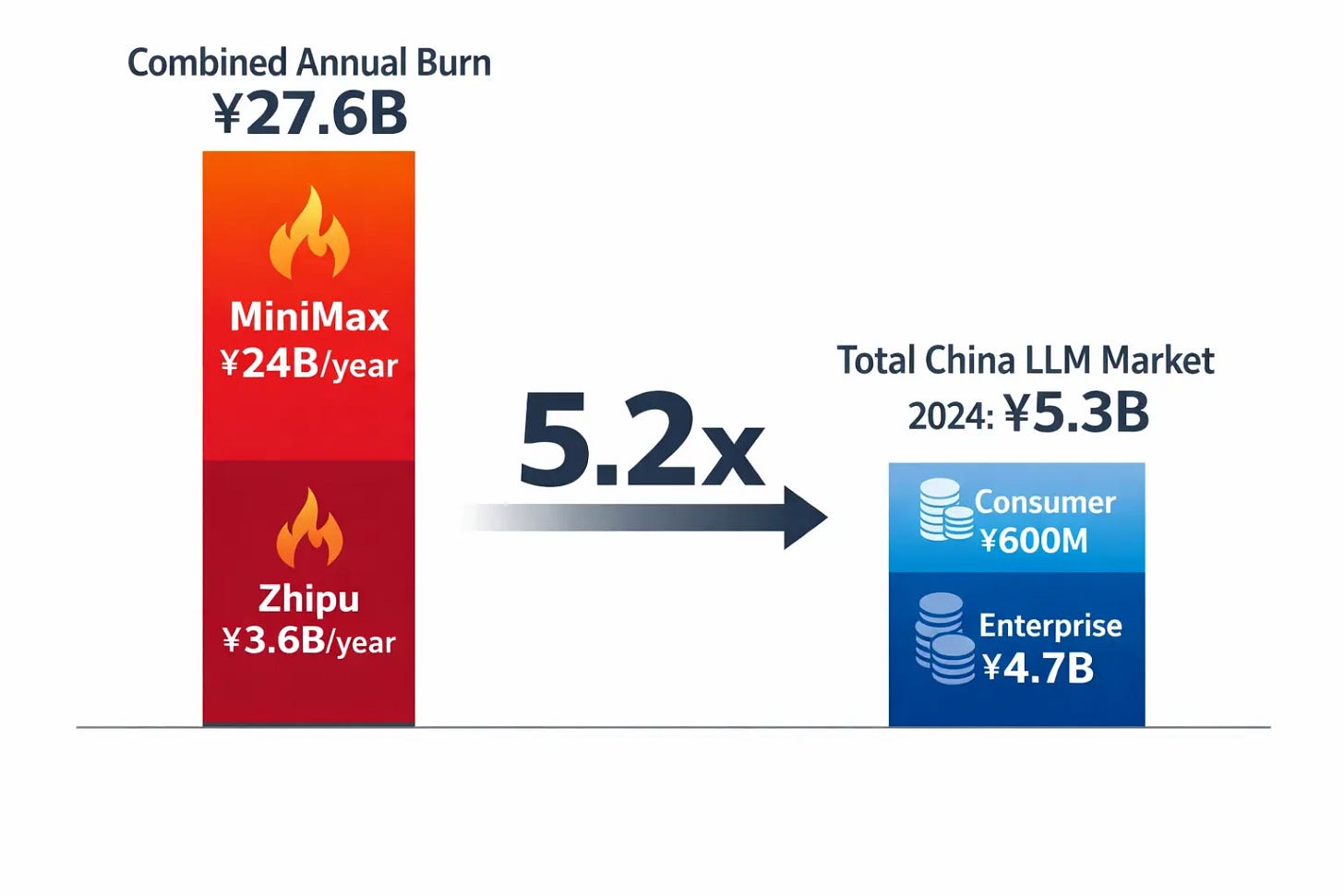

The cash burn is brutal. Zhipu: ¥300 million monthly. MiniMax: ¥2 billion monthly. Zhipu’s mid-2025 reserves stood at ¥2.55 billion. Do the math. Six months later, both companies rushed to file IPOs. The December timing was necessity, not choice.

Here’s what makes this different from typical startup burn. These aren’t ordinary losses from scaling too fast or spending on customer acquisition. Zhipu maintained 56% gross margins in 2024. MiniMax’s B2B segment achieved 69.4% gross margins in the first three quarters of 2025. At the transaction level, these businesses are profitable. Something else is breaking them.

The Profitability Paradox

Start with the numbers that don’t make sense. Zhipu’s gross margin sits at 56%. Strong by any standard, especially for a company selling complex enterprise software. MiniMax’s cloud API business generates 69.4% gross margins. These are SaaS-level economics.

Yet Zhipu lost ¥2.47 billion on ¥312 million in revenue last year. The loss is eight times the revenue. MiniMax lost $465 million on $30.5 million in revenue. Fifteen times.

The gap isn’t explained by typical startup costs. Sales and marketing expenses exist but don’t account for the chasm. Zhipu spent ¥387 million on marketing in 2024. MiniMax allocated similar proportions. The real money disappears elsewhere.

Research and development consumed ¥2.2 billion of Zhipu’s budget in 2024. That’s a 26x increase from the ¥84 million spent in 2022. Within that R&D figure, ¥1.55 billion went directly to compute services. Computing infrastructure alone ate 70% of the entire R&D budget.

MiniMax shows better cost discipline but faces the same fundamental pressure. Training-related cloud computing costs reached $142 million in the first nine months of 2025. The company has managed to improve efficiency. The ratio of training costs to revenue dropped from 1,365% in 2023 to 266% in the first three quarters of 2025. But even at 266%, you’re spending nearly $3 on training for every $1 of revenue.

This creates the first paradox. At the transaction level, these businesses are profitable. Sell an API call or a subscription, you make money. Scale that up, you should make more money. But scaling requires maintaining competitive model quality. Competitive model quality requires constant compute investment. The compute investment grows faster than revenue. The more you sell, the more you lose.

The business model works in theory. It fails in practice because competition determines the required investment level, not customer demand.

Growth That Creates Crisis

The second paradox emerges when you examine what should be good news. Both companies have proven market traction. Zhipu ranks as China’s second-largest general-purpose model developer by revenue, holding 6.6% market share. The company serves 123 large enterprise clients through on-premise deployments, plus over 5,400 customers using cloud services.

MiniMax demonstrates even stronger validation. The company’s AI products reached 27.6 million monthly active users as of September 2025. Cumulative users exceeded 212 million. International expansion succeeded. Roughly 70% of revenue now comes from markets outside China. The company’s Talkie companion app and Hailuo video generation platform gained significant user bases globally.

Token consumption metrics show real usage. Zhipu’s daily average token consumption hit 4.6 trillion in June 2025, up from just 500 million in December 2022. That’s not vanity metrics. Users are actually deploying these models in production workloads.

Yet both companies face existential pressure. Zhipu’s nine-month cash runway forced the IPO. MiniMax’s ¥2 billion monthly burn rate demands immediate funding despite having raised over $1.5 billion. Success isn’t buying time. It’s consuming it faster.

The market size makes this even more puzzling. China’s entire large language model market totaled ¥5.3 billion in 2024, according to Zhipu’s prospectus. Enterprise customers contributed ¥4.7 billion of that. Individual consumers accounted for just ¥600 million.

Do the math. Zhipu burns ¥300 million monthly. MiniMax burns ¥2 billion monthly. Combined, that’s ¥2.3 billion per month. Annualize it and you get ¥27.6 billion. The two companies alone are burning through more than five times the entire current market size annually. And they’re not alone. Multiple other companies compete in the same space.

This isn’t a land grab in a massive emerging market. The market exists but remains modest. The competition intensity belongs to a market ten times larger.

When Strategy Stops Mattering

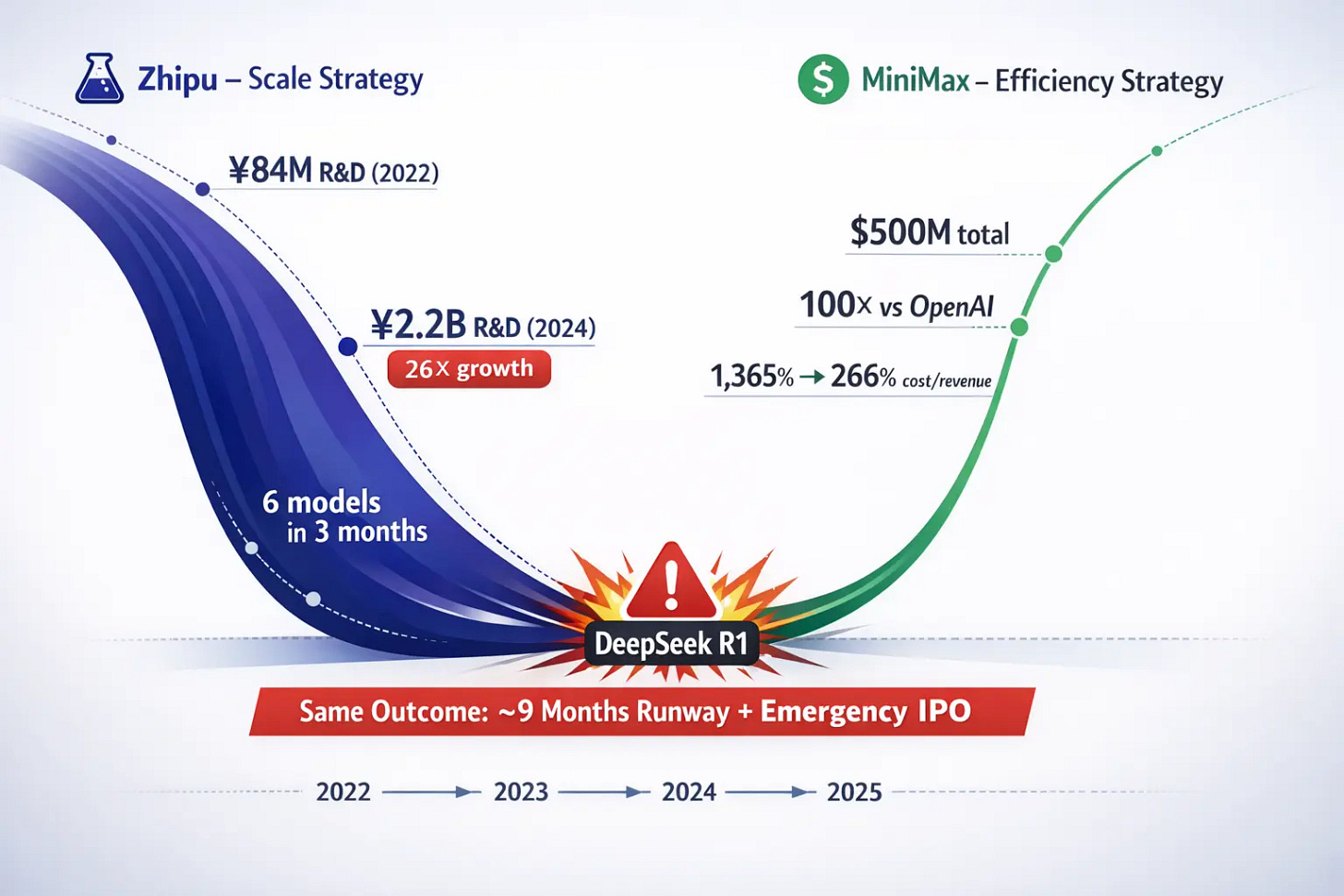

The third insight comes from comparing how these two companies approached the challenge. They chose fundamentally different paths. Both paths led to the same place.

Zhipu bet on scale. The company invested heavily in frontier model development. R&D spending jumped from ¥529 million in 2023 to ¥2.2 billion in 2024. Compute infrastructure dominated that budget. The strategy assumes that leading-edge capabilities justify the burn rate. Stay at the frontier, win the highest-value customers, eventually reach economies of scale.

MiniMax took the efficiency route. The company’s prospectus explicitly positions itself as capital-efficient. Cumulative spending from founding through September 2025 totaled approximately $500 million. The prospectus contrasts this with OpenAI’s estimated $40–55 billion in cumulative investment. That’s a 100x cost difference for comparable multimodal capabilities.

MiniMax optimized everywhere. Training costs as a percentage of revenue improved from 1,365% to 266%. The company achieved competitive quality with far less compute. Their video generation model Hailuo ranks in the first tier globally on independent benchmarks. The text model M2 became one of the most popular models on OpenRouter, a major model aggregation platform.

Yet despite these dramatically different strategies and execution quality, both companies face identical crises. Nine months of runway. Emergency IPO. Unsustainable burn rates. MiniMax spent 1% of OpenAI’s budget and still needs emergency funding.

The proximate cause appeared in early 2025. DeepSeek, a relatively obscure Chinese AI lab, released R1, a reasoning model that matched frontier capabilities at a fraction of the cost. The launch sent shockwaves through the industry. Every major model vendor felt pressure to accelerate iteration.

Zhipu released six core models in less than three months following R1’s debut. That kind of release cadence doesn’t happen with planned budgets. It happens when competition forces your hand. Each model release requires compute for training, evaluation, and deployment. The costs compound.

MiniMax faced the same pressure despite its efficiency advantages. Being 100x more capital-efficient than OpenAI means nothing when a domestic competitor proves you can do more with even less. The bar keeps rising. The cost of staying relevant keeps climbing.

This reveals what makes the situation structural rather than cyclical. Your strategy becomes irrelevant when competitive dynamics dictate behavior. Zhipu chose scale. MiniMax chose efficiency. DeepSeek’s emergence forced both to spend more regardless of their chosen path. In a true market, companies can differentiate on cost, quality, or features. In this market, everyone must match the pace of iteration or become obsolete. The pace keeps accelerating. The costs keep compounding.

Balance Sheets Beat Better Models

Consolidation is already accelerating. The prospectuses mention that many companies with strong backgrounds and funding have already exited. More will follow. The survivors won’t necessarily be the best technologists. They’ll be whoever can access capital longest.

The competitive advantage has shifted from technical capability to balance sheet depth. Zhipu and MiniMax both demonstrated they can build competitive models. That’s no longer sufficient. The question becomes: can you afford to keep building competitive models quarter after quarter as the bar keeps rising? When DeepSeek forces another iteration cycle, can you write another ¥1 billion check?

This creates survivor bias at the industry level. We’ll look at the companies still standing in 2026 and assume they succeeded because they built better products. Many will have succeeded simply because they could afford to keep playing longer. The correlation between model quality and survival is weakening. The correlation between capital access and survival is strengthening.

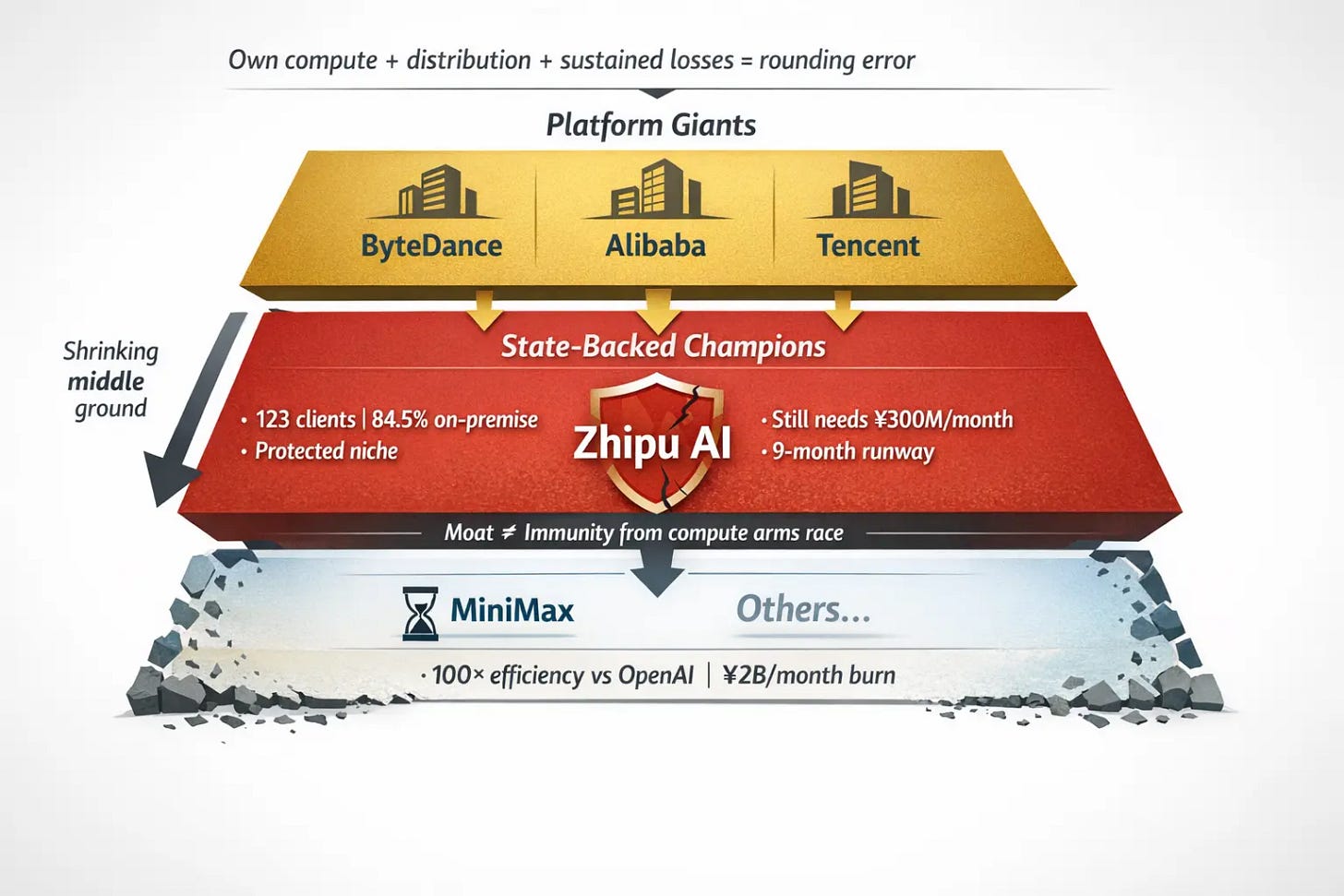

Platform companies gain structural advantage because they can sustain losses that would bankrupt independents. ByteDance, Alibaba, and Tencent control compute infrastructure. They own distribution channels. They generate cash from other businesses. A ¥2 billion annual loss is a rounding error in their consolidated P&L statements. They can treat AI model development as a strategic investment, not a profit center that must justify itself quarterly.

Zhipu’s state backing provides a different kind of advantage, one that’s less familiar to Western investors but equally powerful in China’s political economy. To understand why this matters, you need to understand China’s AI procurement dynamics. Government agencies and state-owned enterprises control most of the high-value AI spending in China. They operate under strict data sovereignty rules that effectively bar foreign models from sensitive applications. They demand on-premise deployments, refusing to send classified or commercially sensitive data to public cloud APIs. And crucially, they prefer working with state-aligned entities over private tech giants like Alibaba or Tencent, whom they view as potential platform threats with their own commercial agendas.

This creates a structurally protected market segment that Zhipu, as a Tsinghua spinout with government investors, uniquely accesses. The company has privileged entry to government and state-owned enterprise contracts that value political alignment and institutional trust as much as technical capability. This is a genuine moat. Private tech giants can compete on price and cloud integration in the commercial market, but they face a trust deficit in the public sector that no amount of technical superiority can overcome.

But this moat, while real, hasn’t exempted Zhipu from the industry-wide compute arms race. Being the preferred vendor for state clients still requires maintaining frontier model capabilities. Government clients may prioritize trust and alignment, but they also demand that the technology works. When DeepSeek raises the bar, Zhipu must match it or risk losing credibility even within its protected niche. The advantage buys market access. It doesn’t buy immunity from capital consumption.

For a deeper analysis of how Zhipu’s state backing shapes its business model and strategic constraints, see: China’s $5.5 Billion AI Unicorn Just Killed Its Product Team

The question has shifted from “can independent model companies survive?” to “why would they?” If maintaining competitiveness requires perpetual capital infusion, and if competitive intensity is divorced from market size, independence becomes a liability. Better to be acquired by or absorbed into a platform with deep pockets and strategic patience. The endgame increasingly looks like a market dominated by platform companies treating AI as infrastructure, not product, and state-backed entities serving the public sector. Independent model companies occupy a shrinking middle ground.

China’s total LLM market is projected to grow from ¥5.3 billion in 2024 to ¥101 billion by 2030, according to Zhipu’s filing. That’s 20x growth over six years. Sounds transformative. The problem is that maintaining competitiveness today requires spending multiples of current market size. If the cost of staying competitive grows faster than the market, then projected market growth is irrelevant. You can win a market that’s growing 20x and still go bankrupt if your costs are growing 30x.

The IPO filings reveal one more uncomfortable truth about how China’s AI economics differ from the West. Enterprise customers, not consumers, drive China’s AI model market. Enterprise revenue accounted for ¥4.7 billion of the ¥5.3 billion total in 2024. Consumers contributed just ¥600 million. This stands in stark contrast to the U.S. market. OpenAI’s CFO has publicly stated that a substantial portion of revenue comes from paying consumers, reportedly around 75%.

This matters because enterprise and consumer business models have fundamentally different scaling characteristics. Consumer AI products can achieve viral adoption with relatively low customer acquisition costs. Enterprise sales require long cycles, custom deployments, and ongoing support. Zhipu’s on-premise deployment model, which generates 84.5% of revenue, serves only 123 clients. That’s high-touch, high-cost sales. Each client generates meaningful revenue, but scaling requires adding more high-cost relationships, not just turning on more servers.

The model works when you can amortize massive R&D costs across thousands of customers. It breaks when competitive pressure forces you to keep investing in R&D at 26x growth rates while your customer base grows linearly. You’re spending like a platform company while selling like a consultancy. The economics don’t converge.

Zhipu’s recent restructuring reflects this reality. The company reportedly dismantled its standardized product center in favor of delivery-focused business units, doubling down on custom project work for government clients. This pivot may provide more predictable revenue and better align with what its state-backed investors want. But it doesn’t solve the fundamental problem: even a project-based services model requires continuous frontier model development to remain competitive. The capital demands of AI development persist regardless of how you package and sell the capability. You can change your business model. You can’t escape the compute arms race.

On Zhipu’s strategic pivot from product-led growth to government services, see: China’s $5.5 Billion AI Unicorn Just Killed Its Product Team

A Race Against Cash, Not Competitors

These IPO filings aren’t graduation ceremonies. They’re desperate searches for the next fuel tank. Both companies have built impressive technology. Both have proven their models can compete globally. Both have validated their business models at the unit economics level. None of it matters if you run out of money in nine months.

The competition centers on who runs out of cash last. That’s a capital endurance test. Model quality and business model validation matter less than cash runway and capital access. This reframes everything about how investors should evaluate China’s AI model sector.

The questions change. Can this company afford to keep having a good model? Does market growth justify the burn rate? How many more funding rounds can they raise before dilution becomes unacceptable? What happens when the next DeepSeek forces another iteration cycle?

The answers from these IPO filings are sobering. The business models work. The technology is competitive. The gross margins are healthy. The economics still don’t add up. The cost of staying competitive grows faster than revenue. Maybe that changes as models commoditize and compute costs decline. Maybe China’s market grows fast enough to support these burn rates. Maybe platform integration creates new monetization opportunities. But none of those maybes have materialized yet, and both companies are running out of time to wait for them.

That’s the structural trap these filings reveal. Build a competitive model, win customers, grow revenue, improve margins. Execute flawlessly on every dimension investors typically care about. None of it saves you when the cost of staying competitive outpaces everything else. Zhipu can secure government contracts. MiniMax can optimize compute efficiency to 1% of OpenAI’s cost. Strategic advantages exist. Protected niches are real. But in a market where one competitor’s breakthrough forces everyone to match the investment, no moat is deep enough to escape the capital consumption spiral.

The October analysis of Zhipu’s transformation highlighted how China’s political economy shapes AI business models. These December IPO filings reveal why even the most strategically positioned companies can’t escape the economics. Zhipu is becoming a state-backed AI services company with exclusive access to lucrative government contracts. But it still faces the same nine-month runway as everyone else. The golden cage provides customers. It doesn’t provide immunity from the compute arms race.

Welcome to China’s AI model market, where success is measured in months of runway, where strategic advantages buy time without ensuring sustainability, and where IPOs are lifelines rather than victories. The question isn’t whether these companies will go public. They will. The state backing ensures that. The question is whether going public solves anything beyond buying another year or two of survival. Whether the capital markets can provide enough fuel for companies to outlast the compute arms race. Whether the market grows fast enough to justify the burn rates before the cash runs out.

On that question, the filings are ominously silent.

About Hello China Tech

This analysis is free. Hundreds of investors, strategists, and operators pay for premium because when China tech news breaks, they need frameworks and implications—not just information.

Premium subscribers get FlashPoint analysis within 48 hours of major developments, deep-dive research on emerging opportunities before consensus forms, and proprietary assessment methodologies for navigating China’s tech landscape.

The difference between understanding China’s tech revolution and profiting from it is the quality of your analysis.

Awesome analysis!

A few thoughts:

1. China LLM market of 5.6B RMB (<$1B) is tiny compared to Western countries (US and Europe ~$4-6B each), which highlights a fundamental problem with Chinese AI models - monetization.

2. Generally most Western LLM players suffer from the same problem - Anthropic also burned $5B+ on $1B revenue in 2024, but then in 2025 it should reach ~$9B revenue with $2-3B burn. Revenue should be increasing faster than costs in the future.

3. Totally agree with your analysis on Zhipu, it’s hard to efficiently monetize enterprise software clients, they will keep struggle with scale and market size.

4. On Minimax I slightly disagree. Because 70% of their revenue is not from China and it’s mostly B2C, the 5.6B RMB market size in China is not really relevant to them. They have much higher upside.

5. Do you think China’s government will let Zhipu and Minimax go bankrupt? With the crazy demand for these two companies among domestic (and even foreign) investors, they can keep raising rounds, although valuation and dilution might be an issue.

6. Have you looked at Moonshot? What is the unit economics situation there?

Superb analysis - eye opening!