Humanoids Are Not Just Cars With Legs

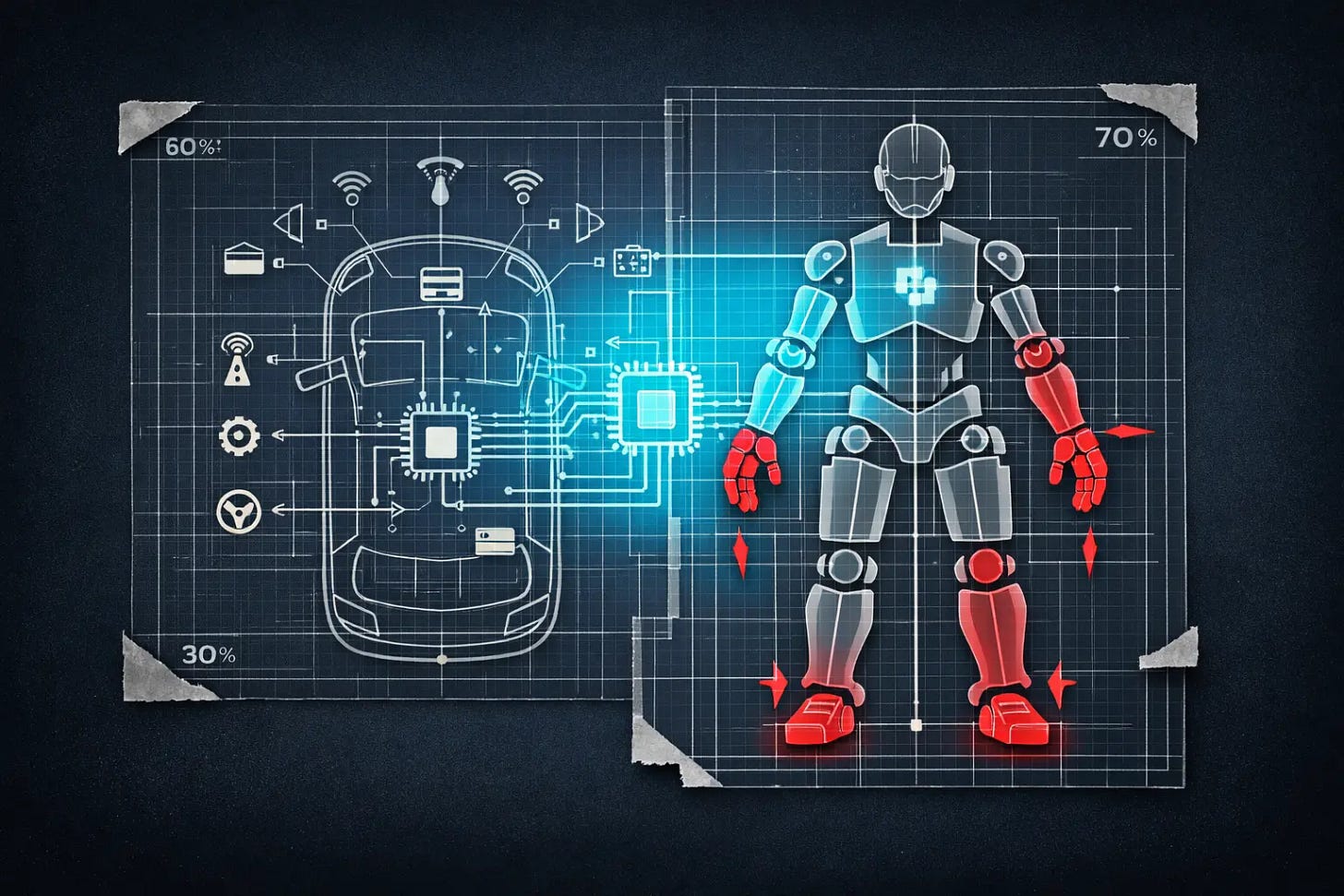

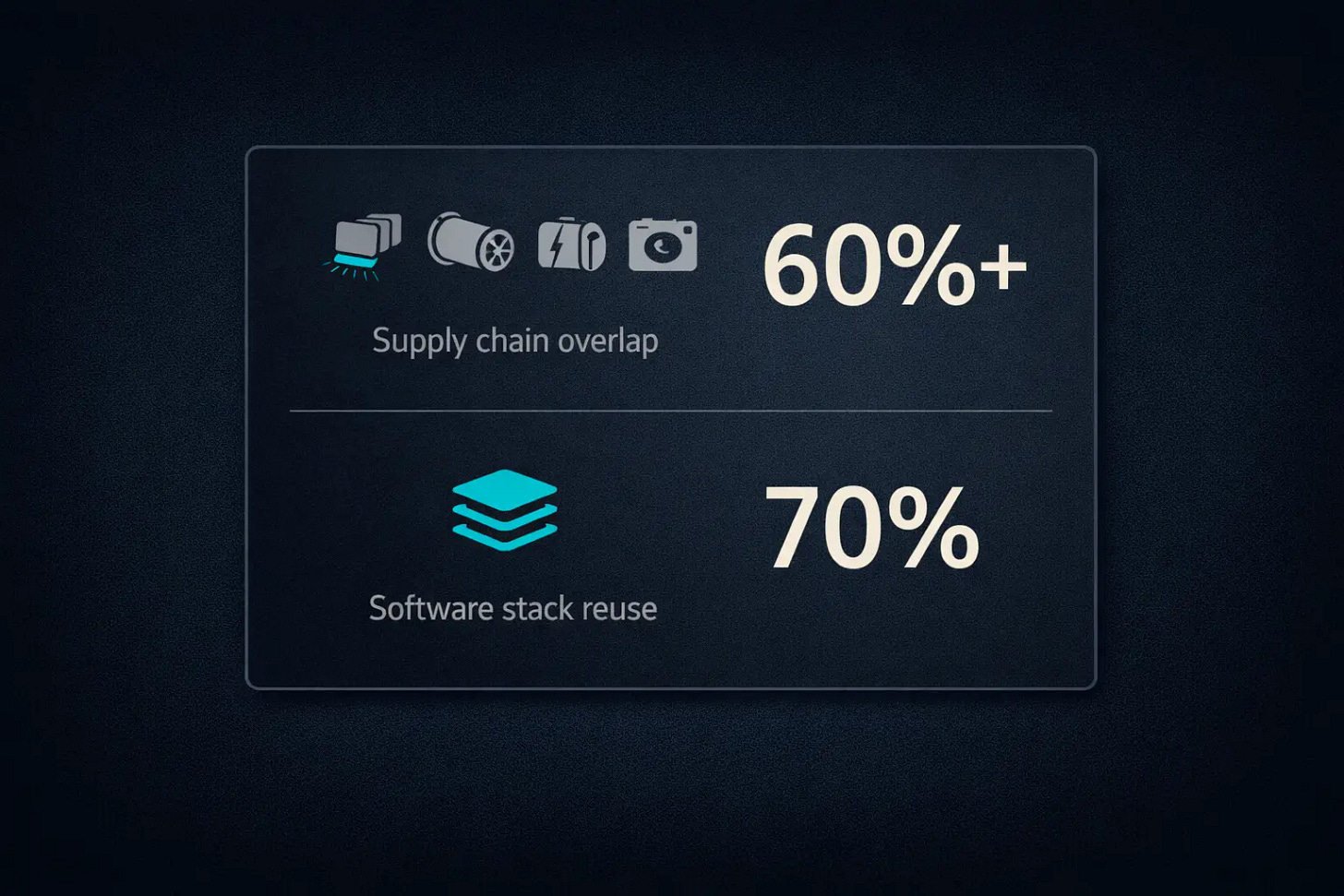

Chinese carmakers cite a 60% supply-chain overlap and 70% software reuse. Early evidence suggests the hard 30% decides the outcome.

On February 1, 2026, a humanoid robot named IRON took its first steps inside a shopping mall in Shenzhen. Built by XPeng, China’s most technology-focused electric vehicle maker, IRON had debuted three months prior at a company showcase. Its gait was so natural that critics accused XPeng of hiding a human inside the shell. CEO He Xiaopeng tore open the robot’s leg casing on stage to expose its mechanical interior, visibly emotional as he asked the audience to accept that the machine was real.

At the mall, IRON fell.

He Xiaopeng compared the moment to a child learning to walk. But XPeng has been working on robots for six years. It acquired a robotics company in 2020, built a four-legged robot horse, pivoted to humanoid form in 2022, and appeared alongside Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang at CES 2025 in the keynote’s lineup of 14 humanoid robots, with XPeng as one of the few automakers represented. Six years of work. And the robot could not stay upright in a shopping mall.

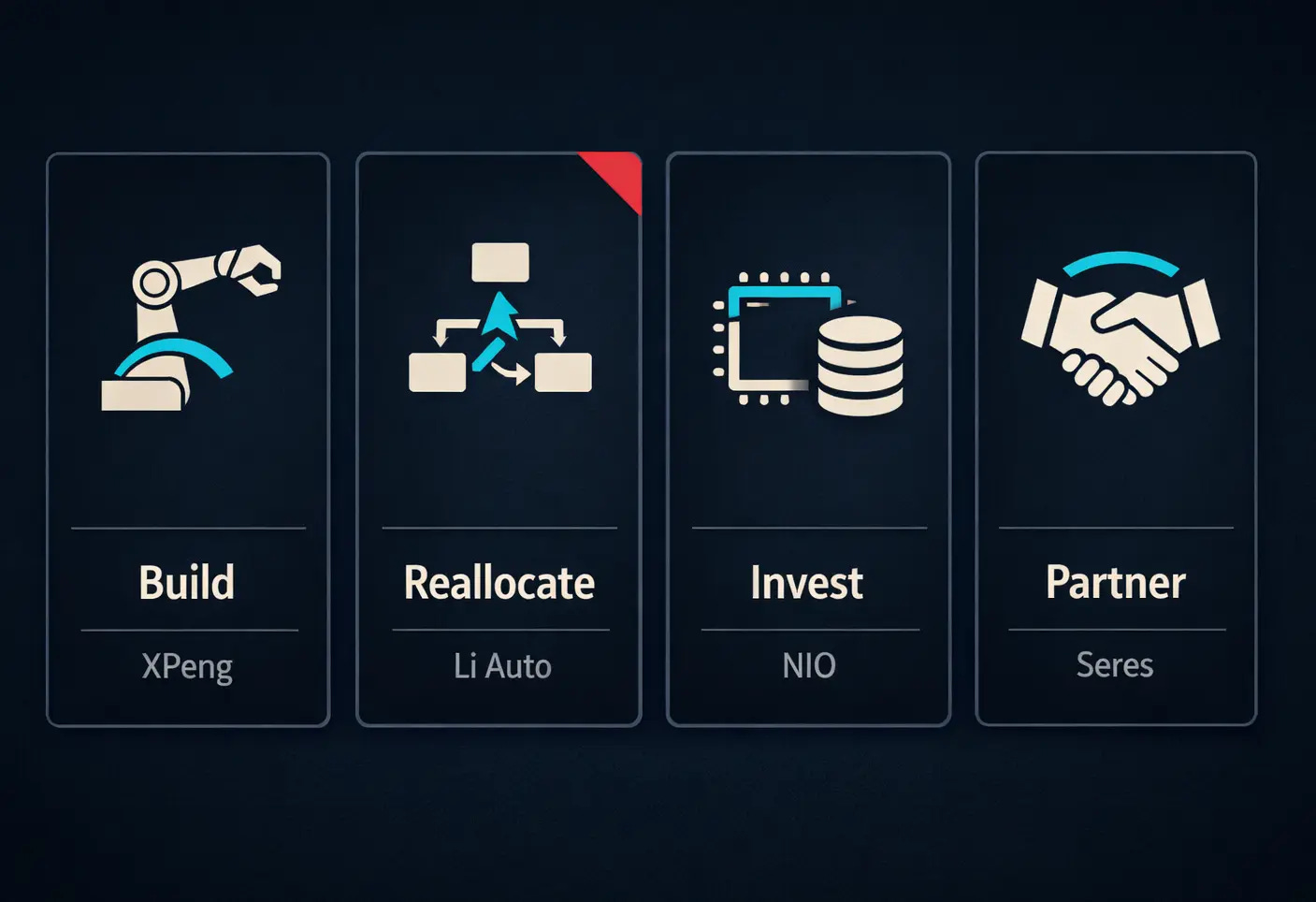

The fall matters beyond XPeng. Fifteen Chinese car companies have entered the humanoid robot field, according to Kaiyuan Securities, a Chinese brokerage. They are building, investing, and partnering their way into a technology they believe runs parallel to what they already do. Two numbers underpin this belief. CITIC Securities, one of China’s largest investment banks, estimates that the hardware supply chains for smart vehicles and humanoid robots overlap by more than 60 percent: sensors, motors, batteries, cameras, and compute chips serve both product categories. Separately, XPeng claims that its robot and car reuse 70 percent of the same AI software stack, spanning perception algorithms, motion planning, and domain controllers.

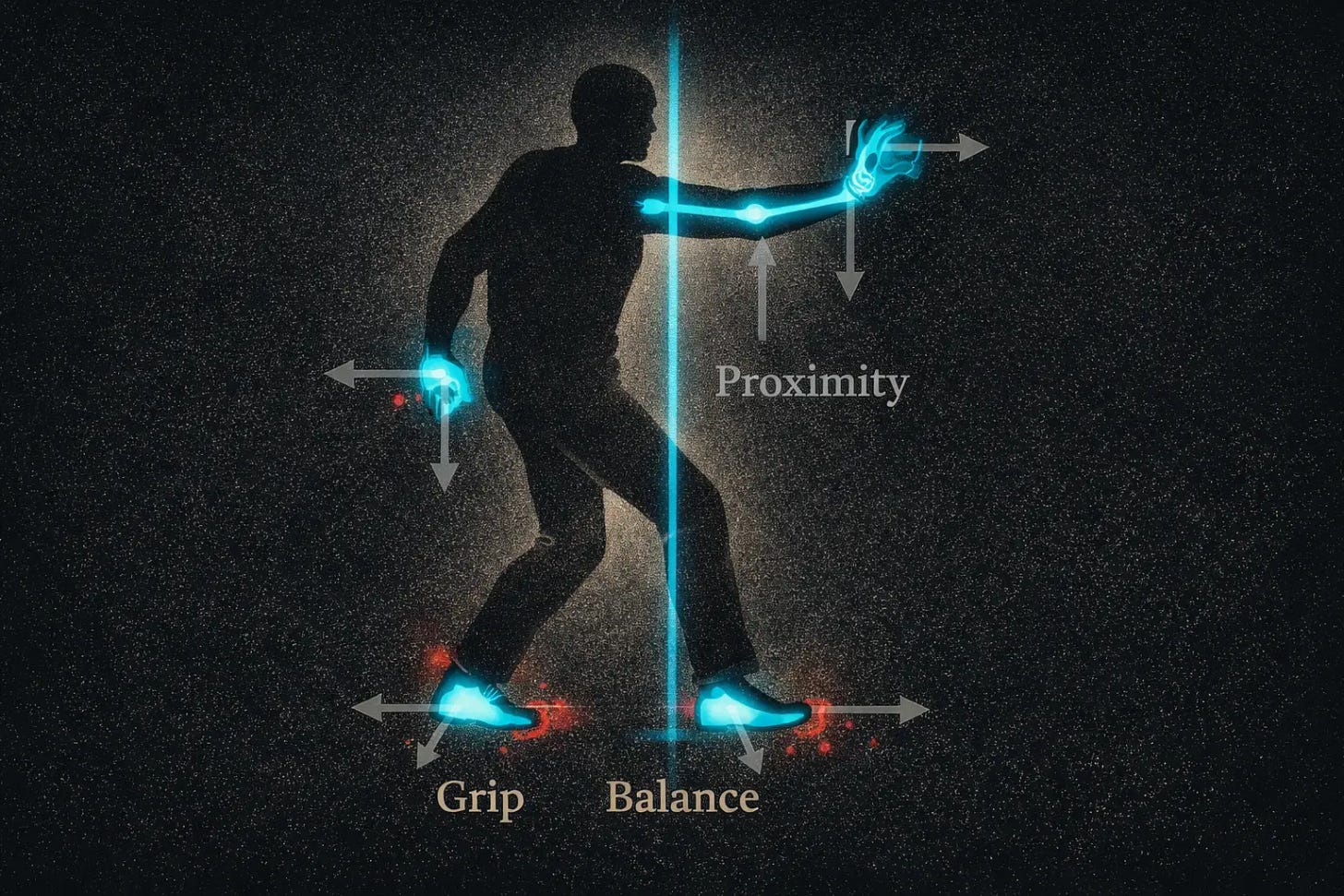

Together, these figures form the structural foundation of the car-to-robot pivot. If the overlap is real and sufficient, automakers carry a meaningful advantage over pure-play robot startups. If the remaining gaps, in dexterous manipulation, dynamic balance, and close-range human interaction, prove to be where the true difficulty concentrates, these companies are reorganizing their engineering cores around a premise that physics may not support.

The question extends beyond China. Tesla’s Optimus program rests on the same logic. Elon Musk has halted production of the Model S and Model X to free factory lines for robots and tied his compensation milestones to delivering one million Optimus units. But China’s electric vehicle market, with dozens of brands locked in a punishing price war, is generating a wider and faster set of experiments. Four companies show how one shared assumption leads to very different wagers.

What the Bridge Promises

XPeng’s approach is the most direct. On February 3, two days after IRON fell, the company merged its autonomous driving and smart cockpit divisions into a single unit called the General Intelligence Center. One foundation model will handle perception, decision-making, and motion control across the car, the cockpit, and the robot, drawing on shared sensor hardware, domain controllers, and AI infrastructure. The reasoning follows a clean line: if a car can perceive its surroundings, plan a route, and execute, a robot needs the same capabilities in a different physical form.

Li Auto, the EV maker that built its brand on range-extended family SUVs, is moving faster and risking more. On January 26, CEO Li Xiang held a company-wide meeting and announced that Li Auto would build humanoid robots. The autonomous driving department was dissolved. Its chief, Lang Xianpeng, the architect of Li Auto’s self-driving strategy, was reassigned to lead the new robot team. AI evaluation and data labeling groups followed him.

The timing reveals the motivation. Li Auto had paused robot development in late 2024, calling the technology premature. What shifted in the fourteen months since was not any breakthrough in robotics. Li Auto posted a net loss of 625 million yuan (roughly $86 million) in Q3 2025, ending eleven consecutive profitable quarters. Revenue fell 36 percent year-over-year. When reports of the company’s robot ambitions began circulating in late January, its U.S.-listed shares rose roughly 7 percent in a single session.

NIO, China’s premium EV brand, rejected the builder’s path entirely. CEO Li Bin has indicated that NIO will not develop robot hardware, at least for now. His stated focus is on NIO’s proprietary chip program and on positioning the company’s technology as a supply chain asset for the broader robotics industry. Rather than assembling an internal robot team, NIO’s venture capital arm has backed at least three embodied intelligence companies over the past year: LimX Dynamics, a Shenzhen humanoid robot company that raised $200 million in its latest round; Linghou Robotics, a component and assembly firm that has shipped over 2,000 units; and Yuanli Lingji, a venture backed by Ant Group, the fintech company behind Alipay.

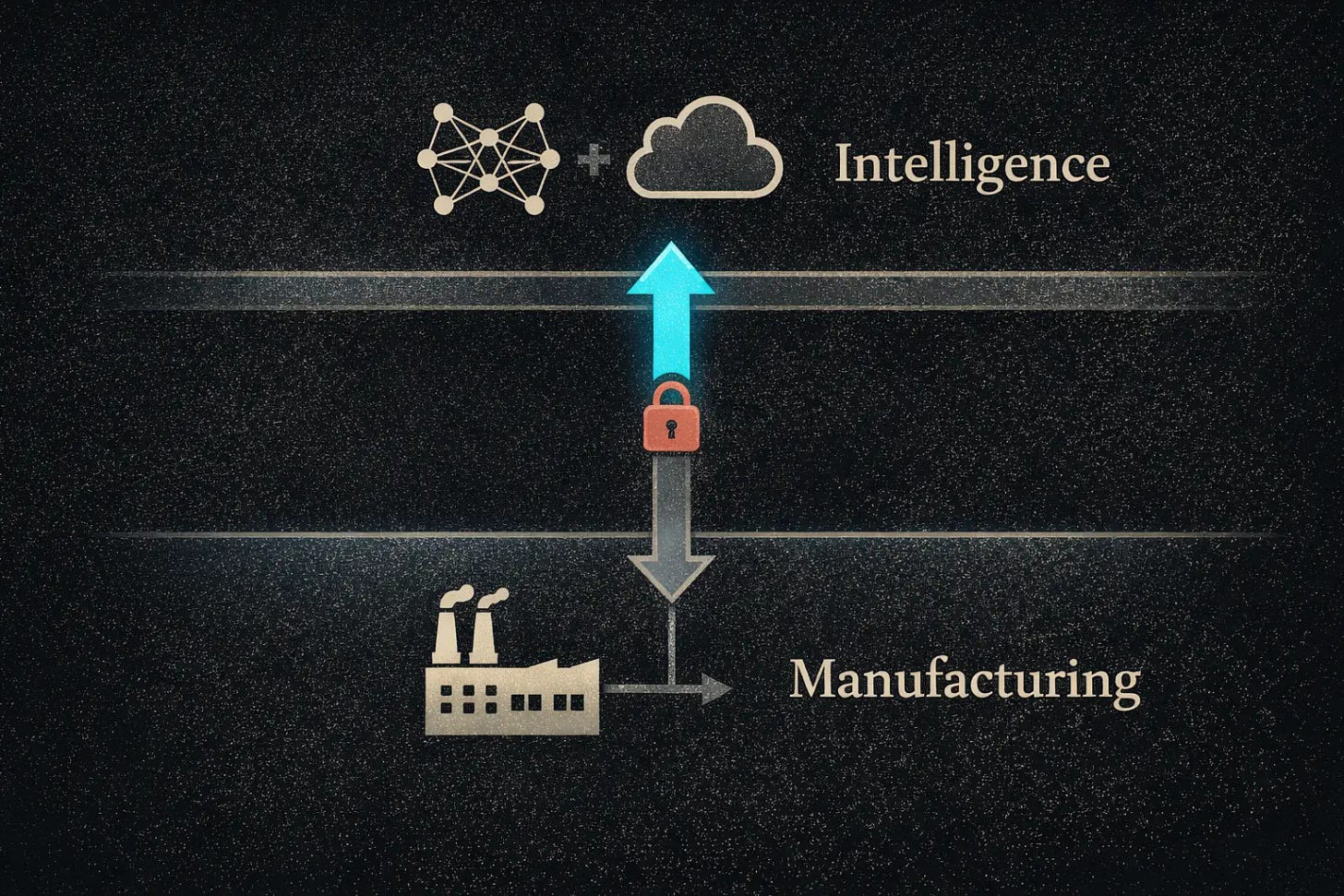

Seres followed a playbook that already transformed its business. The company manufactures Huawei’s best-selling smart vehicles: Huawei provides the software and brand, Seres provides the factory. That partnership lifted Seres from near-irrelevance to China’s second most valuable automaker, a roughly twelvefold increase in market capitalization over five years. When Seres entered robotics, it replicated the formula. In October 2025, it signed a preliminary cooperation agreement with Volcengine, the cloud and AI arm of ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company, to co-develop intelligent robot technology. Under the proposed arrangement, ByteDance would contribute AI algorithms, computing power, and multimodal models, while Seres would contribute manufacturing capability and industrial test scenarios. The deal remains a framework agreement. Specific projects, financial commitments, and timelines have not been disclosed.

Four companies. One shared foundation: the technology stack behind a smart car will carry over to a humanoid robot.

Where the Bridge Ends

Evidence from three directions suggests the bridge is shorter than its builders assume.

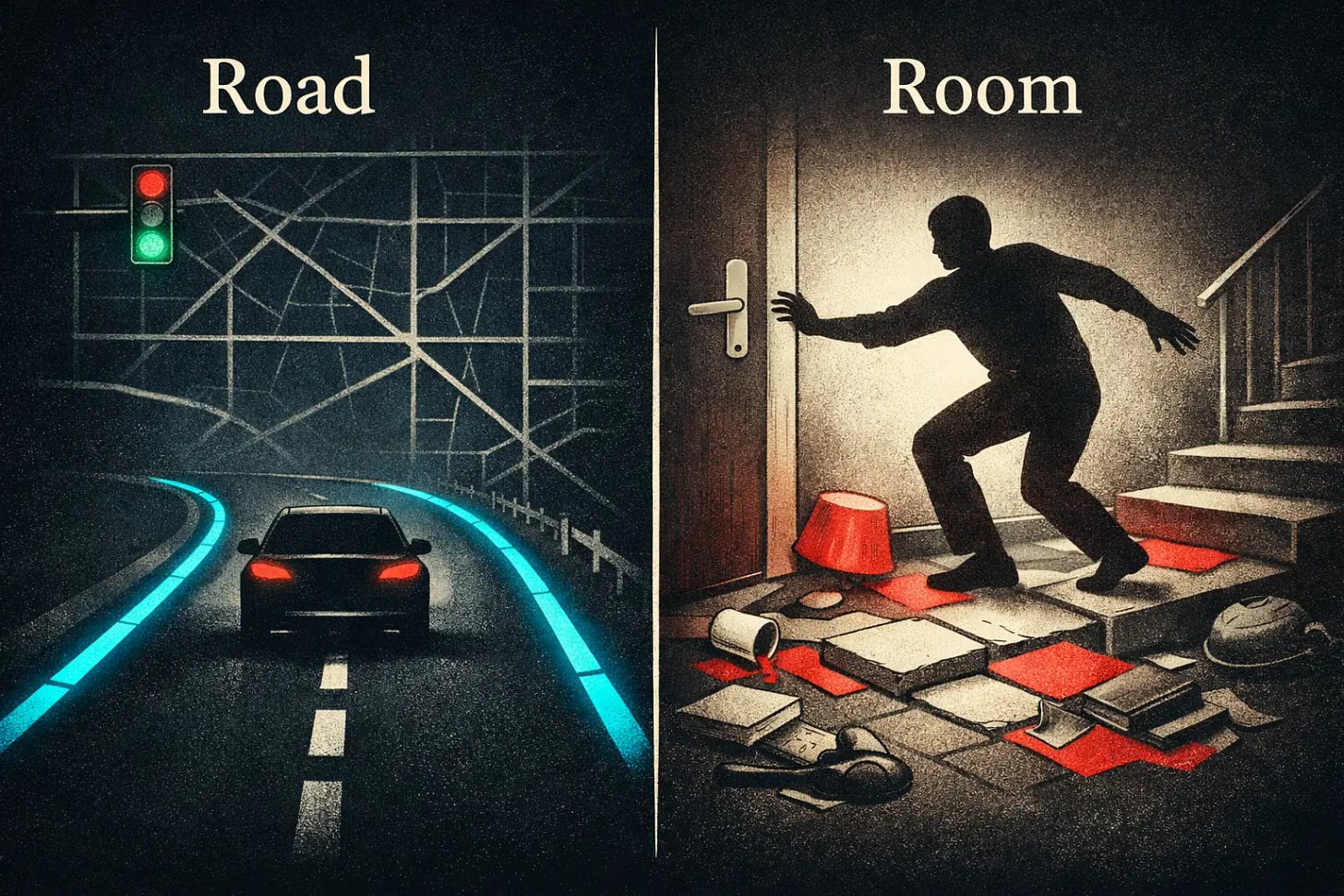

The first is the raw technical distance between driving on roads and moving through rooms. Traffic is constrained by lanes, maps, and norms. Rooms are not. Lanes are painted. Traffic signals follow fixed patterns. The physics of forward motion at speed is well-modeled. Humanoid robots face the inverse: unstructured spaces where they must open doors, grip small objects, climb stairs, and navigate around obstacles that shift without warning. The dexterity, force control, and whole-body coordination required for these tasks sit well beyond anything in a vehicle’s control architecture. Musk has argued that Optimus is harder than major vehicle programs like the Model X, though he’s also said Starship is harder.

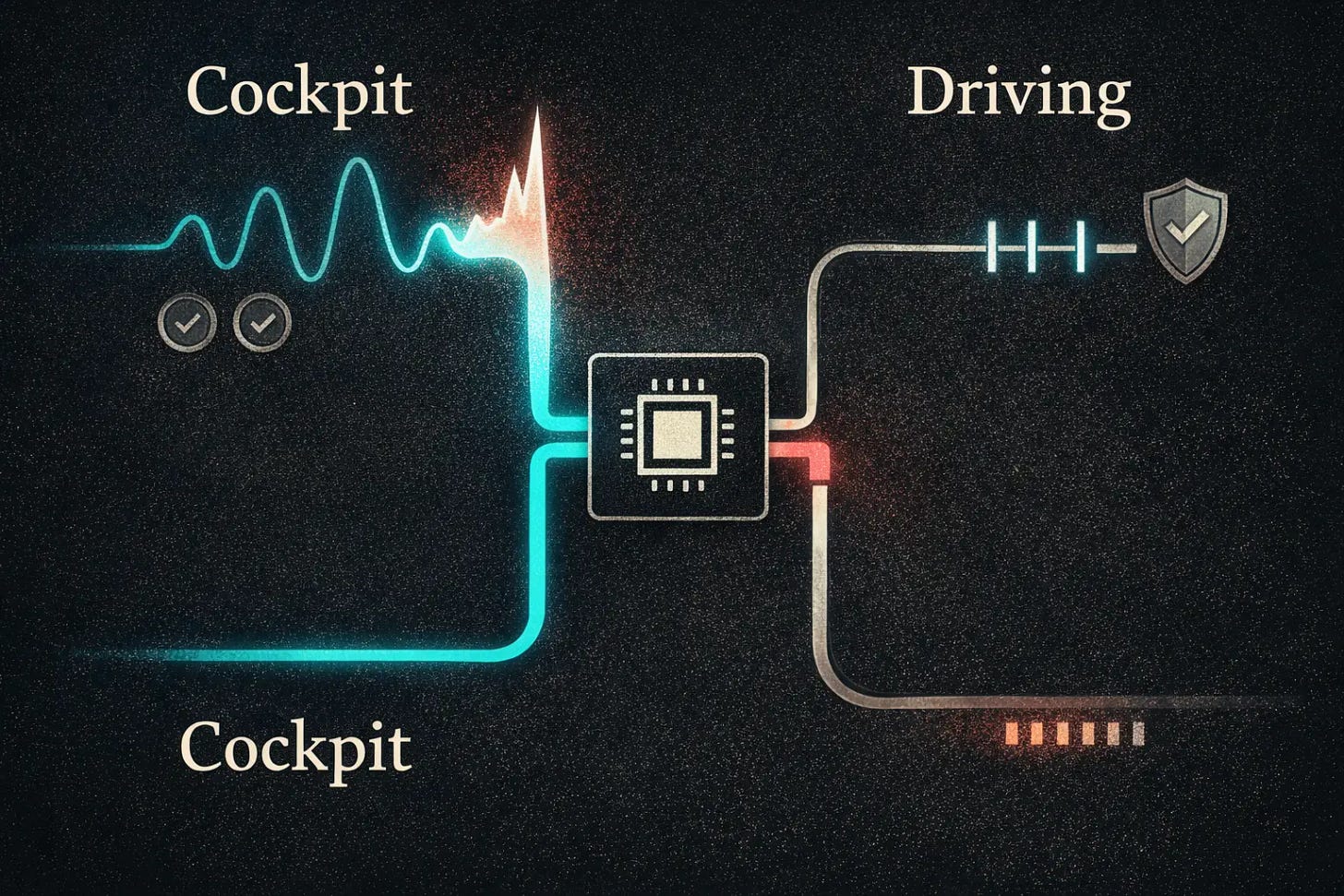

The difficulty surfaces even in the step before robotics. Both XPeng and Li Auto reorganized partly to achieve what the industry calls cockpit-driving fusion: combining the car’s interactive AI with its autonomous driving system into one unified intelligence. This alone is proving stubborn. The two systems operate under fundamentally different constraints. A smart cockpit tolerates errors; a wrong song recommendation is an inconvenience. An autonomous driving system demands millisecond-level determinism; a single miscalculation is a safety event. Merging the two onto shared computing hardware risks one starving the other of processing power at a critical moment. Additional obstacles compound the challenge: different safety certification standards, different software update cadences, and different engineering cultures between cockpit and driving teams, as detailed in reporting by Jiemian, a Chinese financial publication. If unifying AI inside a car poses this many challenges, coordinating a walking, grasping, stair-climbing body represents a different order of complexity.

The second signal comes from talent. If the car-to-robot bridge were solid, the best engineers would stay inside automakers and walk across it. Many are heading the other direction. The founder of XPeng’s original robotics subsidiary departed to start his own company. Former autonomous driving leaders from XPeng, Li Auto, Huawei’s automotive division, and Horizon Robotics, a major Chinese autonomous driving chip company, have co-founded at least five embodied intelligence startups. These engineers recognized the robot opportunity and concluded they would move faster outside a car company.

The third signal is competitive. Robot companies that never relied on automotive technology are running ahead. Unitree, whose robots danced on the Spring Festival Gala, China’s most-watched annual broadcast, reported shipping 5,500 units in 2025. Agibot, a well-funded humanoid robot startup, has reported revenue approaching one billion yuan. LimX Dynamics has released a modular robot platform and what it describes as the industry’s first embodied agentic operating system, enabling robots to plan and execute multi-step tasks without human direction. These companies were built for robotics from the ground up. They are delivering product while car companies are still redrawing org charts.

The Cost of Crossing

The automakers that committed to building robots internally face a bind that tightens with each step forward.

XPeng and Li Auto are pulling their strongest autonomous driving talent into robot programs. Li Auto’s position is the most exposed. Its top self-driving executive now leads robots. The team that built the company’s competitive edge in driving intelligence has been distributed across three new groups. If the shared technology premise holds, this reallocation will prove farsighted. If the premise falls short, Li Auto risks weakening its standing in the car market, where Huawei-powered competitors plan to field 25 new models in 2026, without closing the gap with robot startups that hold multi-year leads in hardware and deployment.

NIO’s strategy inverts the risk profile. Funding the robot supply chain rather than building robots avoids cannibalizing car engineering. But if embodied intelligence becomes the next platform shift, an investor captures a smaller share of value than a builder.

Seres is replicating a partnership model that delivered extraordinary results in vehicles. The structural question persists: when the core intelligence belongs to a partner, margins tend to follow the intelligence provider, not the hardware assembler.

These are Chinese variations of a question approaching every global automaker. Musk has committed Tesla’s next chapter to the same transfer thesis. China’s fifteen parallel experiments will produce data faster and in greater volume than any single company could generate. The early readings counsel caution. The overlap between cars and robots is real in sensors, compute hardware, and perception software. It thins rapidly once a robot must manipulate objects with precision, maintain balance on uneven ground, or work safely within arm’s reach of a person.

He Xiaopeng said IRON’s stumble looked like a child learning to walk. A closer parallel may be a highway racer entering an obstacle course. The vehicle shares some relevant capabilities. Certain skills carry over. But the terrain is entirely different. And terrain, ultimately, determines who finishes.

Interesting article. A couple of thoughts. Would you know in which order Chinese car companies entered robotics? I.e. which one first, Xpeng, NIO (even just by investing in robotics companies) or Li Auto?

Car companies that are advanced in autonomous driving have very large data to interfere and apply to humanoid robots, especially those companies that shifted early on their lidar approach to intelligent “vision”.

That means a robot can move within any environment/settings (including stairs) and generate in real time a digital twin of its context.

Also, physical AI, approach means humanoid robots teach themselves through virtual or real world interactions. That itself is huge.

Pure play humanoid robot companies lack that vastly amount of data and will take them a long time to catch up.

Finally the gala robots show with martial art was indeed impressive but also very much rehearsed like a choreography.

There is no doubt in my mind that China will lead technological advancement in humanoid robots too as it has done with Solar Power, EVs, etc