XPeng Builds Robots While Losing Money on Cars

The Chinese EV maker is pouring cash into AI and robots as losses mount. Its survival depends on proving this pivot makes business sense.

When XPeng Motors unveiled its IRON robot last week, the machine’s gait was so fluid that internet sleuths immediately accused the company of hiring a human actor in a suit. Chairman He Xiaopeng had to release a candid video physically unzipping the robot’s chassis to prove its mechanical nature.

This theatrical moment serves as a perfect metaphor for XPeng itself right now: a company desperately trying to prove that the advanced intelligence it claims to possess is real, functional, and scalable, rather than just a sophisticated costume worn by a traditional automaker.

XPeng is at a pivotal juncture. It is attempting one of the most difficult maneuvers in the technology industry: pivoting from a hardware manufacturer in a commoditized market to a high-margin AI platform. Given the brutal realities of the Chinese EV market, this is survival, not strategy.

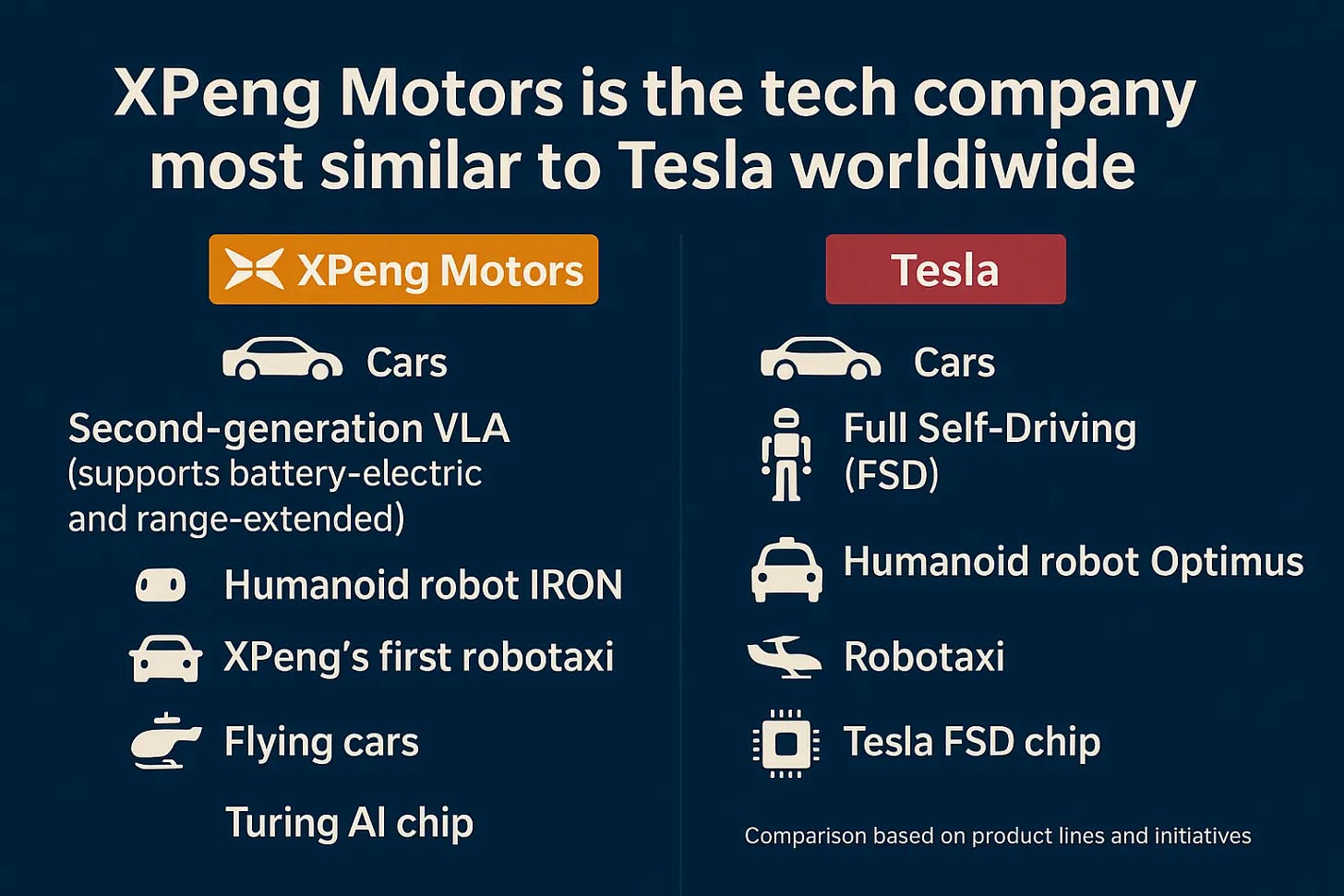

This deep dive explores why XPeng is betting the company on “Physical AI,” how its technological roadmap mirrors Tesla’s while its execution diverges radically, and whether its strategy of building an open “federation” can compete with Elon Musk’s closed empire.

China’s EV Bloodbath

To understand why a company still losing hundreds of millions of dollars a quarter would pour vast resources into humanoid robots and flying cars, one must first appreciate the crushing gravity of the Chinese automotive market in middle 2025.

The market has entered a phase of merciless consolidation. The “price war” is no longer a temporary tactic. It is the permanent state of play. In this environment, pure-play EV manufacturers face a daunting landscape defined by two superpowers:

BYD (The Scale Monster): With its total vertical integration (from lithium mines to batteries to semiconductor manufacturing), BYD has achieved a cost structure that no competitor can match. It can profitably sell EVs at price points that bleed rivals dry.

Huawei (The Ecosystem Giant): Huawei does not make cars, but its “Harmony Intelligent Mobility Alliance” (HIMA) is rapidly conquering the premium segment. By offering a turnkey solution encompassing the cockpit OS, autonomous driving stack, and electric powertrain, Huawei has become the de facto “brain” for numerous automaker partners, squeezing independent players who insist on developing their own tech.

XPeng sits uncomfortably between these two forces. It lacks BYD’s massive scale to win on price, and it lacks Huawei’s diversified balance sheet to weather a prolonged war of attrition. Historically, XPeng differentiated itself through superior autonomous driving technology. However, as advanced ADAS (Advanced Driver Assistance Systems) becomes commoditized by suppliers like Huawei and Momenta, that moat is narrowing.

For XPeng, remaining solely a car company is a slow path to irrelevance. It needs an escape velocity. It needs a technological differentiator so profound that it reclassifies the company entirely in the eyes of both consumers and investors.

The Turing Chip Bet

XPeng’s answer to this trap is what Chairman He calls “Physical AI.” This is a unified technological architecture designed to power any machine that moves, whether it has four wheels, two legs, or eight propellers.

Superficially, this roadmap looks identical to Tesla’s. Both companies are developing proprietary silicon, end-to-end AI models, and varied hardware endpoints. However, a closer look at XPeng’s recent disclosures reveals a strategy doubling down on brute-force compute to achieve a breakthrough.

The Silicon: Brute Force at the Edge

The cornerstone of this new strategy is the “Turing” chip. While most competitors are content using standard NVIDIA Drive Orin-X chips (delivering 254 TOPS, or trillions of operations per second), XPeng has designed its own silicon specifically optimized for the massive transformer models used in modern AI.

XPeng claims a single Turing chip delivers 750 TOPS. But they aren’t just using one. Their new P7 sedan uses three (2,250 TOPS), and their planned Robotaxi uses four (3,000 TOPS). This is a staggering amount of edge compute power.

Why such overkill? Because XPeng is betting that the only way to solve the “long tail” of autonomous operation is through massive, uncompressed AI models running locally on the machine. The long tail includes the freak occurrences, complex human interactions, and chaotic edge cases that standard autonomous systems struggle with. XPeng is trading higher hardware BOM (Bill of Materials) costs now for the potential of true Level 4 autonomy later.

The Ghost in the Machine: VLA and Emergence

This massive compute infrastructure exists to serve one master: the second-generation VLA (Vision-Language-Action) model.

Traditional autonomous driving stacks are modular. One system perceives the world (“that is a red light”), another plans the path (“I should stop”), and a third executes the control (“apply brakes”). The industry is moving toward “end-to-end” models, where a single neural network takes raw sensor data in and outputs control commands.

XPeng claims its new VLA model has achieved “emergence.” In AI terms, this refers to a model becoming large and complex enough to develop capabilities it was never explicitly trained for. XPeng showed examples of its vehicles correctly interpreting complex, non-standard hand gestures from traffic police. This is a scenario notoriously difficult to hard-code.

If this “emergence” is genuine and scalable, it validates XPeng’s entire thesis: that a single, powerful “AI brain” can intuitively understand the physical world, regardless of the body it currently inhabits.

Why XPeng Cannot Copy Tesla

While the architectural diagrams align with Tesla’s, XPeng’s execution is uniquely shaped by China’s industrial environment.

Hardware: The “Soft” Advantage

The IRON robot provides the clearest example of this divergence. Tesla’s Optimus is a marvel of traditional “hard” robotic engineering, relying on expensive, custom-designed electromechanical actuators. It’s a very Silicon Valley approach: solve the problem through rigorous first-principles engineering.

XPeng took a different path. Operating out of Guangzhou (the heart of the Pearl River Delta manufacturing hub), the company leveraged local supply chain strengths. Industry observers noted that IRON’s remarkably fluid gait is likely achieved through novel hardware choices, including advanced 3D-printed elastomer materials that act as artificial “muscles” and a flexible, biomimetic spine.

This “softer” hardware approach allows for rapid iteration and more naturalistic movement without the extreme mechanical complexity (and cost) of Tesla’s rigid designs. It is a pragmatic shortcut that allowed them to reach a visually impressive prototype faster.

Business Model: The Federation vs. The Empire

The most critical differentiator, however, is strategic posture. Tesla operates as a closed empire. It wants to own everything: the chip, the software, the car, the robot, and the eventual Robotaxi network. It shares nothing.

XPeng, lacking Tesla’s trillion-dollar market cap, knows it cannot conquer the world alone. It is building a federation.

We see this in two key strategic moves:

The Volkswagen Alliance: XPeng is actively monetizing its tech stack. Its deal to license its electrical architecture (EEA) to Volkswagen is more than just a revenue stream. It is a vital endorsement. It proves that legacy automakers, struggling with software, see genuine value in XPeng’s architecture. XPeng is now pushing to license its newer VLA capabilities, effectively trying to become a Tier 1 supplier of intelligence.

The Open Robotaxi Network: Unlike Tesla’s plan for a proprietary ride-hailing app, XPeng is opening its Robotaxi SDK to partners, starting with Amap (Gaode Maps, owned by Alibaba). XPeng realizes that to gather the oceanic volumes of data needed to compete with Tesla’s global fleet, it needs partners who already have massive user bases.

The Cash Burn Question

XPeng’s just-released Q2 2025 financials provide a brutally clear picture of its strategic bet. The company is burning cash it can barely afford to secure a future it cannot guarantee.

The headline numbers look strong. Revenue hit a record RMB 18.3 billion ($2.5 billion), up 125% year-over-year. More importantly, gross margin climbed to 17.3%, a staggering turnaround from the razor-thin margins of previous years. Vehicle margin specifically hit 14.3%, proving XPeng can finally make real money on the hardware it sells.

Yet, this newfound hardware profitability is being immediately funneled into the AI furnace.

Despite record revenue, XPeng still posted a net loss of RMB 480 million ($66 million). While this is a 63% improvement over last year, it highlights a critical reality. XPeng is not using its profits to build a safety cushion. It is using them to accelerate R&D. Research spending surged 50% year-over-year to RMB 2.2 billion ($303 million) in a single quarter.

This is the crux of the gamble. XPeng is now a company with two distinct operational modes: a stabilizing, increasingly profitable car business, and a voracious, cash-burning AI research lab.

With RMB 47.6 billion ($6.6 billion) in cash reserves, XPeng has a runway. The runway is not infinite. Sustaining concurrent revolutionary R&D programs (custom silicon, end-to-end models, humanoid robotics, and eVTOL aircraft) is a staggering financial burden.

If the VLA model fails to deliver a decisive, revenue-generating advantage in its cars within the next 12 to 18 months, investor patience for the “robotics” narrative may wear thin as those cash reserves dwindle. XPeng is betting that its escape velocity will kick in before its fuel runs out.

What We Still Don’t Know

XPeng has successfully demonstrated technological ambition. The IRON robot walks with startling confidence. The Turing chip delivers massive compute power. The VLA model shows signs of genuine intelligence.

But the commercial questions remain unanswered.

Can XPeng’s Robotaxi economics work in Chinese cities where regulatory approval remains uncertain? The company has deployed pilot fleets in Guangzhou and other cities, but the path to profitable operations at scale is unclear. Chinese regulators have been cautious about fully autonomous vehicles. Timeline uncertainty creates revenue uncertainty.

Will legacy automakers pay meaningful licensing fees for the VLA platform? The Volkswagen partnership validates the technology, but we do not yet know the economic terms. Is this a high-margin software licensing business, or a low-margin component supply relationship? XPeng’s ability to achieve “tech company” valuations depends entirely on this answer.

How long can XPeng’s RMB 47.6 billion cash reserve sustain this level of R&D spending? At the current burn rate of roughly RMB 2 billion per quarter on R&D alone, plus ongoing capital expenditures for manufacturing expansion, the company has roughly five years of runway before external financing becomes necessary. Five years sounds comfortable. In the hyperspeed world of Chinese EVs and AI, it is not.

These questions cannot be answered with product demos or impressive prototypes. They require tracking XPeng’s partnerships, regulatory approvals, cost structures, and competitive positioning quarter by quarter.

XPeng has built an impressive technology platform. Whether that platform translates into a sustainable, profitable business model is the trillion-yuan question that will determine the company’s fate.

📊 What’s Next: We’re tracking the metrics that matter: partnership economics, BOM cost trajectories, Robotaxi pilot performance data, and regulatory developments. Premium subscribers get bi-weekly deep dives analyzing whether XPeng’s AI pivot can generate real cash flow.

That was really informative. As an Xpeng car owner, I follow their progress with great interest.

This whole strategy and bet can be doomed by single U.S. decision - putting XPeng on blacklist and cutting them off from TSMC. With ban in place , there will be no Turing chips.