What Changed in China Tech | Issue 1

China’s EV Industry: From Price War to Price Control.

Introducing a new series:

Most China tech newsletters try to keep up with the news.

This one asks a different question: What actually changed over the past week, in a way that will still matter months from now?

Each issue of What Changed highlights concrete signals, surfaces one hidden variable that explains why they matter, and points to what deserves attention next.

Published most Thursdays when genuine directional shifts emerge. Read more about this series →

This Question

Is China’s EV industry shifting from “price war” to “price control”–and what does that mean for the overcapacity cycle?

On December 12, eight of China’s largest EV makers issued near-identical statements within 24 hours. BYD, Leapmotor, Xpeng, Changan, Chery, BAIC, Great Wall, and JAC all pledged to “oppose price fraud and unfair competition.” The trigger: China’s State Administration for Market Regulation had just released draft guidelines explicitly banning automakers from selling vehicles below cost–except for inventory clearance.

This isn’t routine anti-dumping regulation. It signals that China’s EV industry, after two years of brutal price competition, is entering a new phase of the “policy-driven boom to overcapacity” cycle. The government is stepping in not as a referee, but as the largest player reshaping the game’s rules. We tracked five developments that reveal why this intervention is happening now–and what constraints it imposes on the “trial-and-error advantage” that has defined Chinese EV competitiveness.

Five Signals

Signal 1: Industry profitability has hit a crisis point

China’s auto industry operating margin fell to 4.4% in the first ten months of 2025, near a five-year low and below the 6% average for downstream industrial enterprises. In October alone, margins collapsed to 3.9%. Average profit per vehicle dropped to just RMB 14,000 ($1,940)–about half of what a single iPhone generates in profit. For dealers, the pain is sharper: 52.6% reported losses in H1 2025, and 74.4% faced negative margins on certain models.

But the most dangerous signal isn’t industry pain–it’s consumer backlash. The share of buyers delaying purchases in anticipation of further discounts jumped from 28% in 2023 to 45% in 2025. Price wars didn’t stimulate demand; they trained consumers to wait. When waiting becomes the rational choice, pricing becomes a death spiral. Consumers increasingly associate “cheap” with “low quality”: the “one price, one quality” mindset rose from 13% in 2023 to 34% in 2025.

Signal 2: The “no selling below cost” rule gets teeth

The draft Compliance Guidelines for Pricing Behavior in the Automotive Industry doesn’t just ban below-cost sales–it defines cost comprehensively (manufacturing costs + R&D, finance, sales expenses), prohibits nine forms of disguised price cuts (including “upgrading configurations to mask lower pricing”), and mandates clear separation of vehicle price from service fees. Dealers face the same restrictions, with an added ban on “bulk discounts” that large dealer groups use for predatory pricing. The requirement for transparent pricing and fixed delivery dates in contracts closes loopholes that let manufacturers and dealers play pricing games. Critically, the rule applies to both OEMs and dealers, creating enforcement accountability across the distribution chain.

Signal 3: Eight major OEMs responded with coordinated speed

The speed of industry response matters more than the content. In China’s auto industry, coordinated action at this pace only happens when companies see the government’s hand–or when they’re desperate for a coordinated exit from a prisoner’s dilemma. The statements’ identical framing signals both. No major player publicly opposed the guidelines, revealing that the industry collectively welcomes government intervention to end the race to the bottom. BYD’s instant compliance signals something deeper: understanding that this isn’t just rule-following, but aligning with the government’s consolidation preferences.

Signal 4: The MPV market reveals the “tier-skipping” trap

China’s MPV segment accounts for just 3.8% of total vehicle sales–one-eighth of Indonesia’s 30%+ share. But this isn’t market underdevelopment; it’s tier-skipping. China’s auto market, with 353 million vehicles and 3x the per-capita ownership rate of Indonesia, jumped directly from basic mobility needs to premium segments. The “affordable multi-purpose vehicle” tier that dominates Southeast Asia barely exists in China–consumers went straight to premium MPVs like the Denza D9.

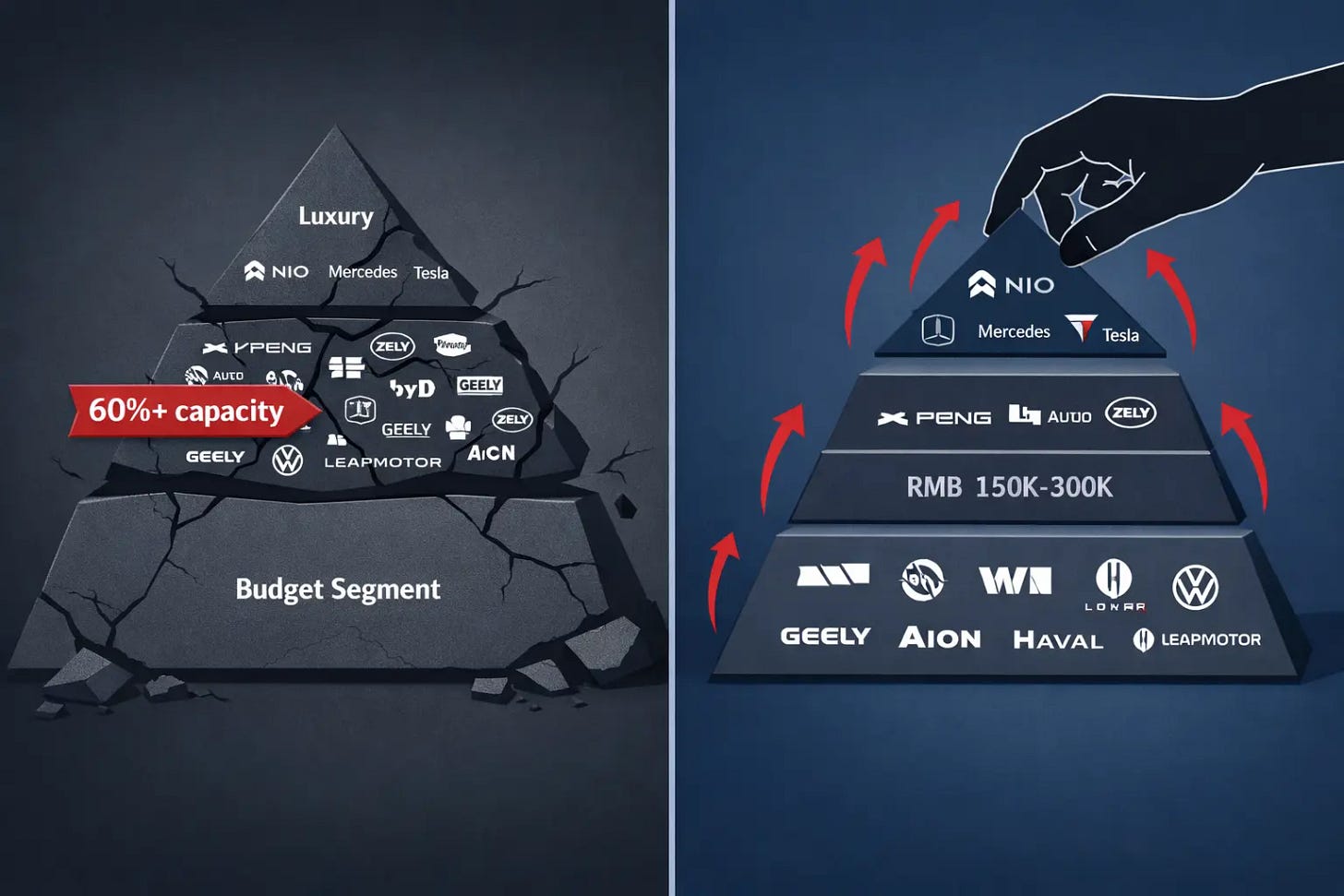

This pattern appears across categories: Chinese buyers skip “good enough” tiers and concentrate in premium segments, intensifying competition at the top. The price war reflects this structural reality: too many players competing in too few viable tiers. When 60%+ of production capacity targets the RMB 150,000–300,000 “mass premium” segment, small demand shocks trigger cascading discounts across the entire tier.

Signal 5: VC/PE investment structure is shifting away from volume plays

China’s VC/PE market saw investment volume surge 30.33% year-over-year in the first 11 months of 2025, but the LP structure shifted: corporate investors’ share rose from 31.3% to 34%, while government platforms declined. More telling, VC-stage investment now accounts for 78% of deal count and 57% of capital–up from prior years–with average deal size dropping to RMB 88 million. Capital is moving earlier and smaller, away from late-stage growth bets on scaling production. While this data covers all sectors, the shift aligns with signs of overcapacity across capital-intensive industries. The message: the era of funding aggressive capacity expansion may be cooling.