The Platform Power Problem: AI Agents in China’s Mobile Internet

ByteDance proved AI agents can work across apps. WeChat proved it controls whether they’re allowed to. The difference explains everything about platform power.

On December 1, ByteDance launched Doubao Phone Assistant on ZTE’s Nubia M153 smartphone. The product demonstrated genuine technical capability. Users could issue voice commands to accomplish tasks across multiple applications. Tell it to find the cheapest coffee across three delivery platforms, and it would open each app, search, compare prices, and place an order.

Within three days, WeChat blocked it. The super app flagged logins as suspicious and forced users to log out. Taobao triggered CAPTCHA verifications. ByteDance disabled WeChat functionality within a week and announced restrictions on financial apps and gaming scenarios. According to Chinese business outlet YiCai, the company had prepared just 30,000 units for what it called a technical verification run.

This sequence reveals something fundamental about platform competition. ByteDance achieved a technical breakthrough. It built system-level AI that can operate across applications without requiring API access. Yet that innovation immediately hit the wall of ecosystem power. WeChat’s mini-program platform serves 949 million monthly users who average 70 interactions per month, according to QuestMobile data cited in the Chinese tech press. Douyin’s mini-programs reach 283 million users. The scale gap is 3:1. But the strategic gap is wider.

The question isn’t simply who will win. It’s how platform power operates to constrain even successful technical innovation–and whether that power ultimately proves decisive. In a previous analysis, I examined ByteDance’s strategic calculations and why it chose this forbidden path despite formidable obstacles. This piece examines the other side: how WeChat’s ecosystem creates structural barriers that technical capability alone cannot overcome.

The Ecosystem Advantage

WeChat’s power stems from a decade of platform building. The app functions as self-contained infrastructure. In Western terms, imagine if iMessage, Venmo, Amazon, and the entire App Store existed within a single application. That approximates WeChat’s role in Chinese digital life.

Mini-programs are the foundation. These are lightweight applications that live entirely within WeChat. Users don’t download them from an app store. They access them through WeChat’s search function, QR codes, or friend recommendations. The format is unique to China’s internet ecosystem. Unlike Western web apps or mobile apps, mini-programs integrate deeply with WeChat’s payment system, user identity, social graph, and messaging infrastructure. All of this happens without leaving WeChat.

QuestMobile data shows over 9.49 billion monthly active users across WeChat’s mini-program ecosystem as of October 2024. Monthly per-user engagement reaches approximately 70 interactions. Mini-programs with over one million users account for 14.1% of the total. Life services, mobile shopping, and financial services mini-programs each serve over 800 million users.

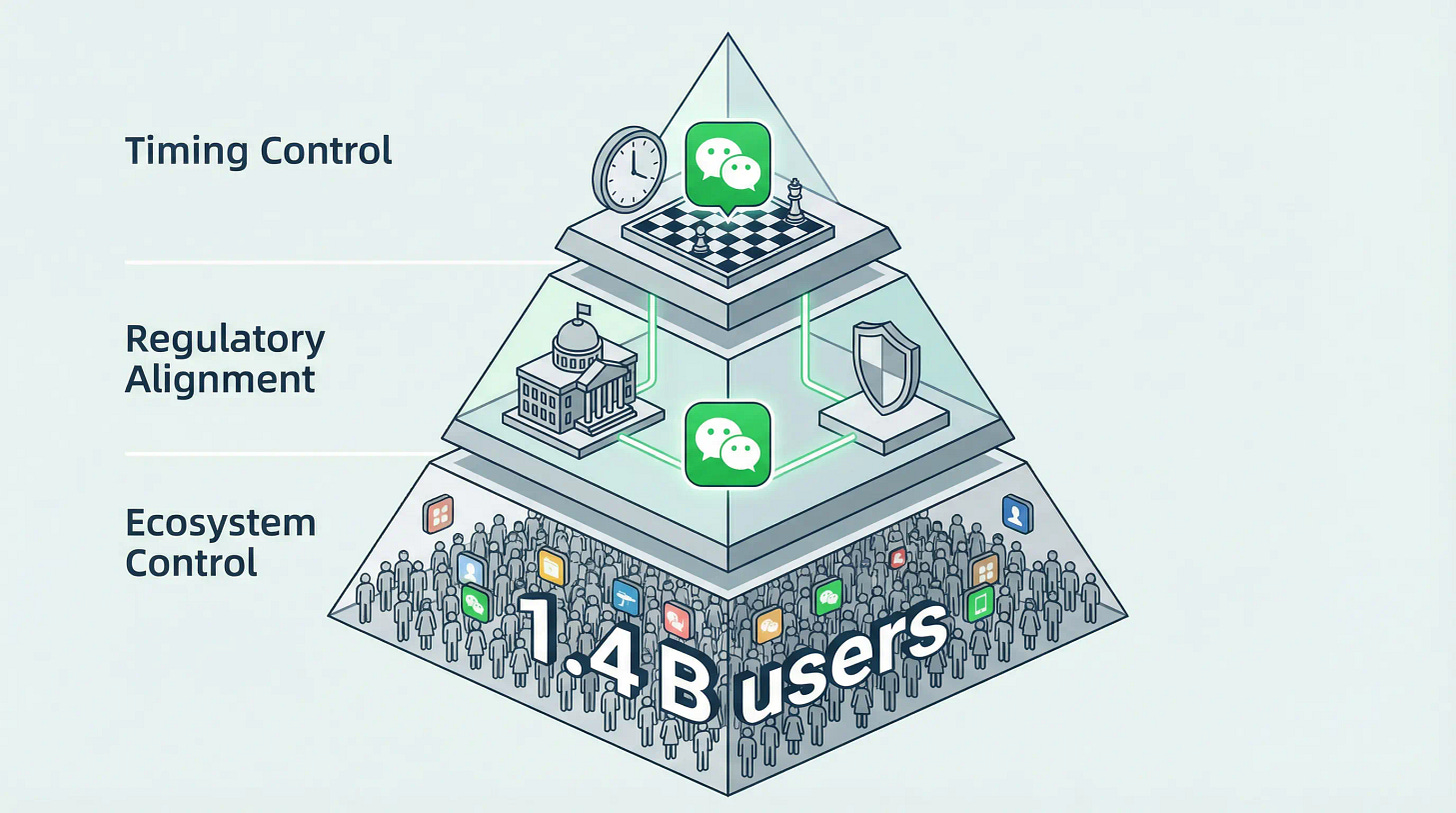

This creates what platform economists call voluntary lock-in. Mini-program developers choose to build within WeChat’s boundaries because the alternative means starting from zero users and zero payment infrastructure. The trade is explicit. Access to 1.4 billion users in exchange for platform dependency.

The structure aligns incentives. Developers aren’t being controlled. They’re accepting a bargain. WeChat provides instant distribution, user identity, payment rails, and social graph. Developers provide services. Both sides benefit. But WeChat controls the on/off switch.

This matters for AI agents because the agent doesn’t need cross-platform access. A WeChat agent can complete the coffee order example entirely within WeChat’s universe. Search through mini-programs. Compare prices from multiple delivery services. Place the order through WeChat Pay. The entire transaction flow stays inside one ecosystem.

Chinese business reports describe this as win-win cooperation. The phrase appears constantly in corporate communications. But here it describes actual commercial structure. Mini-program developers gain revenue. WeChat gains service depth without operational responsibility. The model works because all participants opted in.

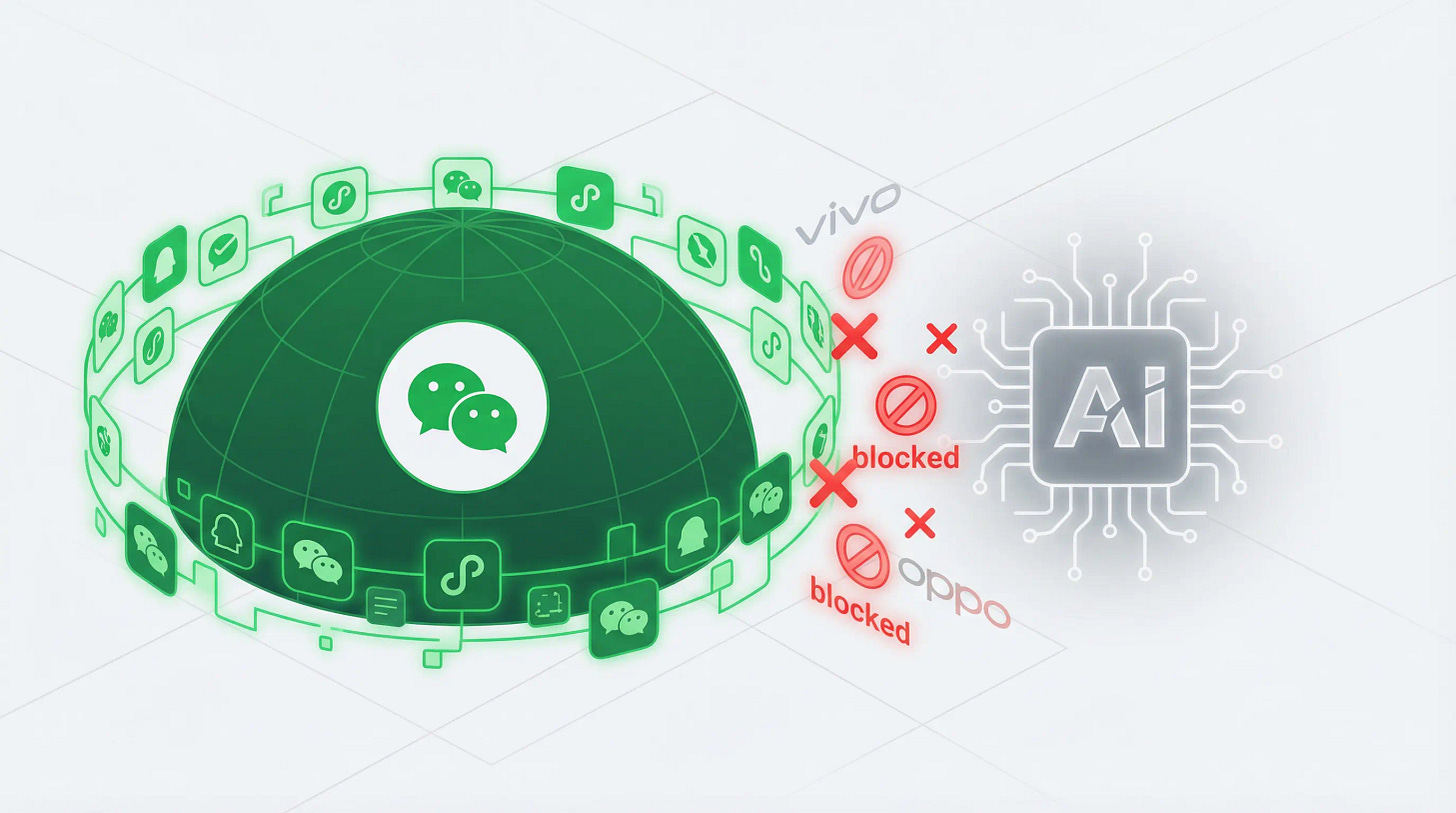

Platform blocking power reinforces this advantage. When Vivo and OPPO attempted similar AI assistant features in their phone operating systems, WeChat removed itself from support lists. Users reported that automatic expense tracking from WeChat transactions and timeline generation from WeChat videos both disappeared. OPPO’s official response stated that WeChat application restrictions prevented the feature. The message was clear. WeChat decides what’s permitted within its ecosystem.

Chinese regulators have also taken notice. According to business media reports, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has been monitoring AI assistants that use screen-capture and automation capabilities. In December 2025, the Cloud Computing Standards and Open Source Promotion Committee released security guidelines requiring dual authorization from both applications and users before AI agents can access third-party apps. These rules don’t force platforms to grant access. They just specify what must happen if access is granted.

This regulatory attention shapes platform behavior. WeChat’s blocking of Doubao reflects both competitive defense and regulatory caution. The company must balance innovation with its role in China’s digital infrastructure. That responsibility actually strengthens its position. Competitors face the same scrutiny but without the established government relationships.

Two Paths, Different Constraints

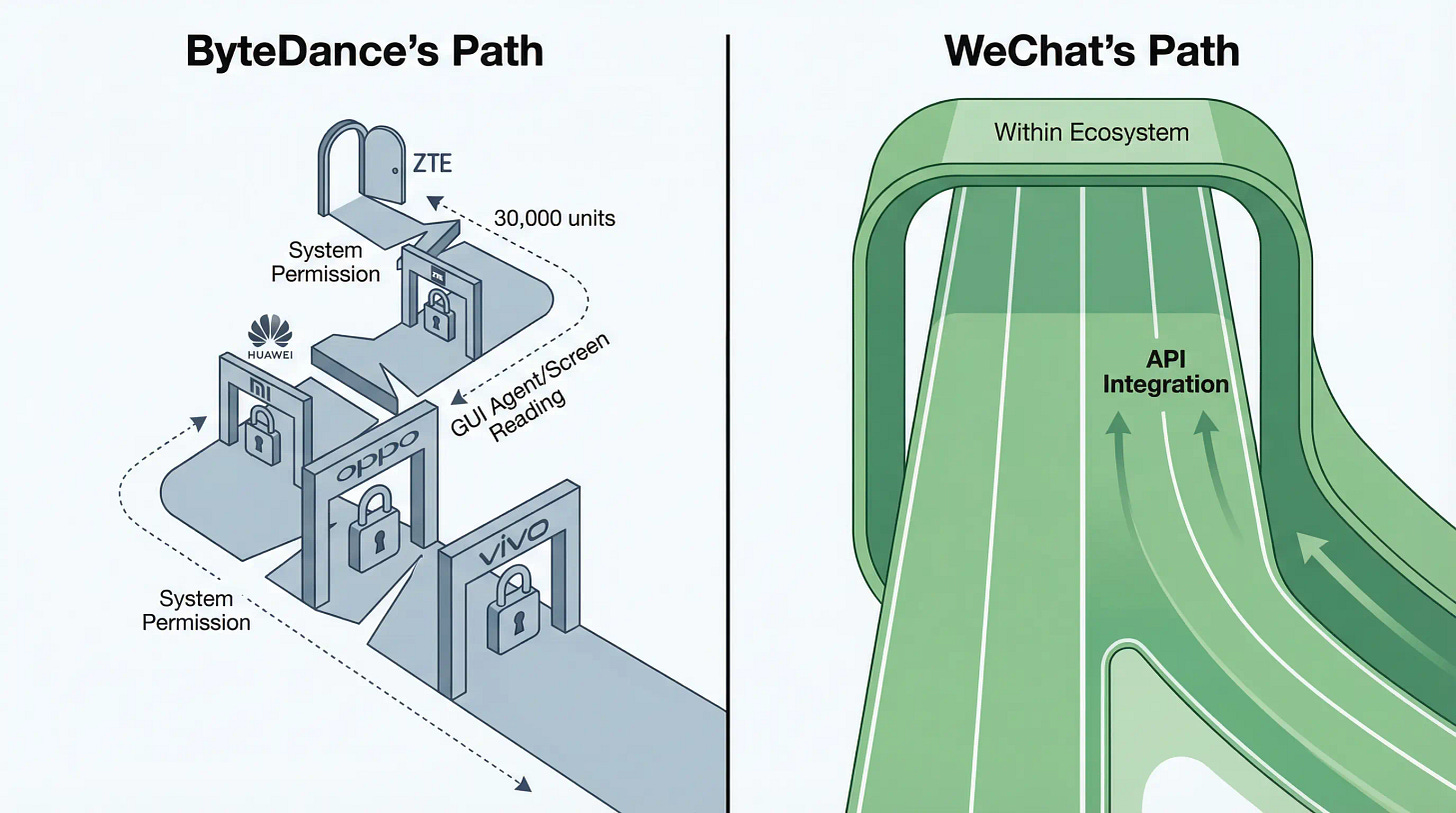

ByteDance faces fundamentally different constraints. The company chose OS-level integration. This approach requires system permissions that mainstream phone makers won’t grant. Huawei, Xiaomi, Vivo, and OPPO are all building AI capabilities into their own operating systems. They see the AI layer as the next battleground for user control. They won’t hand that control to ByteDance.

This explains the ZTE partnership. Nubia occupies a marginal position in China’s smartphone market. According to Chinese business outlet Yicai, industry insiders say the phone is essentially developed by ByteDance itself, with ZTE acting as contract manufacturer. The first batch totaled 30,000 units. Compare this to mainstream flagship launches, which typically prepare 2 to 3 million units. ByteDance clearly isn’t competing in smartphones. It’s testing whether the GUI Agent approach can work at all.

The technical approach reveals these constraints. Doubao doesn’t integrate with apps through official APIs. It uses system-level permissions to simulate human finger taps. The agent reads the screen, interprets what it sees, and clicks buttons like a person would. According to user tests reported by Chinese tech media, Doubao takes about 30 seconds to complete a simple check-in task on JD.com that a human could finish in 10 seconds.

This method is slower and less reliable than API integration. So why choose it? Because API access requires permission from the platforms you’re trying to disrupt. Huawei and Xiaomi both attempted WeChat integration features in their AI assistants. These capabilities were quietly removed. Zhipu AI demonstrated its AutoGLM agent sending WeChat red packets on stage in 2024. By mid-2025, WeChat was no longer supported.

ByteDance’s approach sidesteps this permission requirement. The agent operates at the operating system level without asking apps for cooperation. From the phone’s perspective, it’s just another user tapping and swiping. But platforms can still resist. WeChat’s terms explicitly prohibit third-party software from operating accounts or controlling components. The company acted within 48 hours of Doubao’s launch.

This creates a cooperation paradox. AI agents need cross-application operation to deliver value. But that breadth requires permission from competing platform owners. Platforms won’t grant permission for their own disruption. ByteDance chose the forbidden path. Every seemingly irrational choice becomes rational under this constraint. Partner with a marginal phone maker because mainstream brands refuse. Use inferior screen-reading technology because APIs are closed. Launch early despite limitations because the timing window is closing as phone makers integrate their own AI systems.

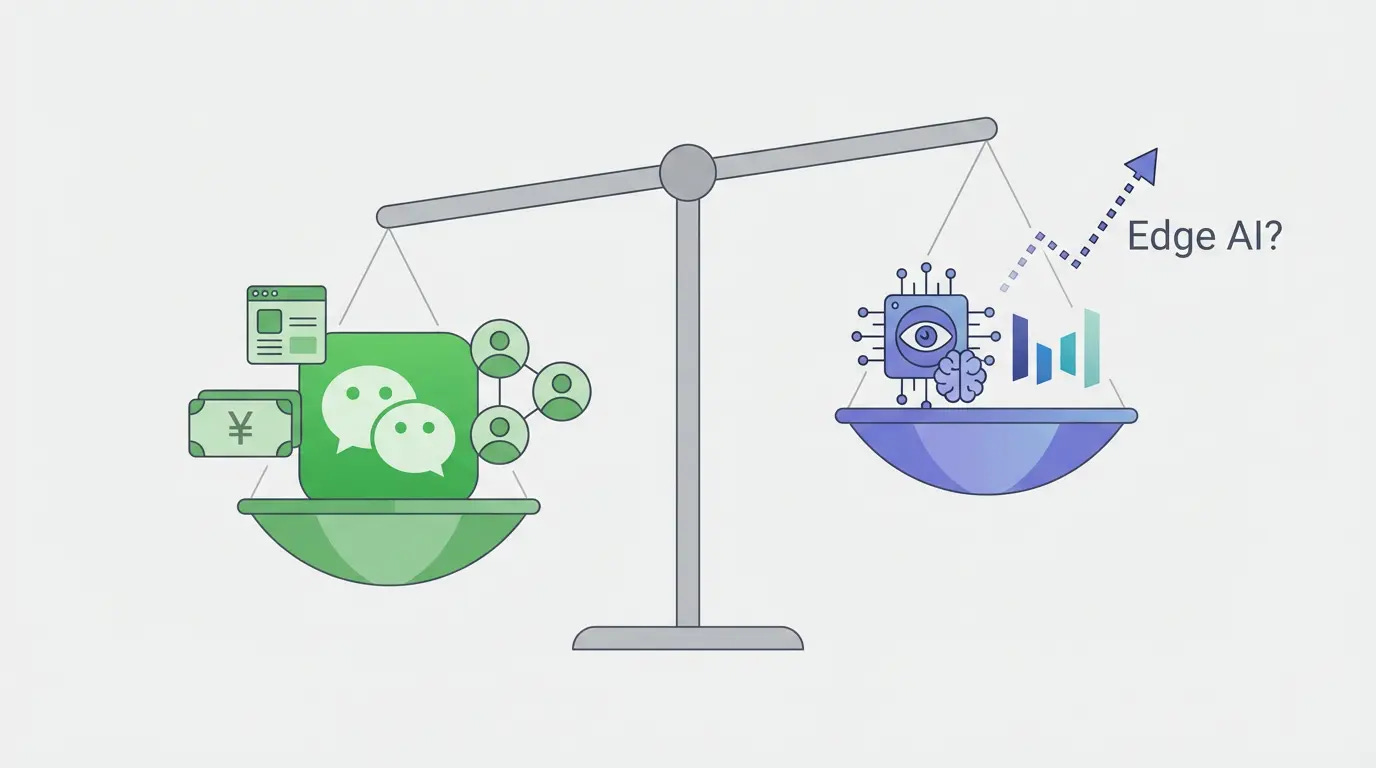

The company is betting that establishing presence now–even with technical limitations and platform resistance–positions it for a future where edge-side AI development or regulatory shifts might redistribute power. Whether that bet proves rational depends on factors still unfolding: the pace of edge-AI maturation, user adoption patterns, and regulatory evolution. I examined the specific tradeoffs behind these choices and ByteDance’s strategic calculations in detail here.

WeChat doesn’t face this paradox. The mini-program ecosystem already provides cross-service operation within controlled boundaries. An agent within WeChat can access millions of services and 949 million users without needing OS-level permissions. This isn’t innovation. It’s integration of existing infrastructure.

Tencent President Martin Lau confirmed this direction in the company’s third quarter 2025 earnings call. He stated that WeChat would eventually launch an AI agent within its ecosystem. But he emphasized the company remains in early development stages. That patience reflects strategic positioning. WeChat holds terrain advantages–though it also faces timing pressures as phone makers integrate AI into operating systems and edge-side AI development potentially bypasses centralized platforms entirely.

What Platform Power Actually Means

This competition demonstrates broader principles about platform economics in China’s internet sector. Three patterns matter.

First, ecosystem control compounds over time. WeChat doesn’t just have users. It has a decade of relationship-building with mini-program developers, payment infrastructure integration, and regulatory understanding about its role in digital infrastructure. Each successful defense against outside agents strengthens this position. ByteDance must prove agents work despite platform resistance. WeChat can observe, wait, and integrate proven approaches without bearing discovery costs.

Second, regulatory frameworks reinforce incumbent advantages. In Western markets, antitrust regulation sometimes forces platforms to open APIs or allow competitive access. Epic Games sued Apple over App Store policies and won partial concessions. The EU’s Digital Markets Act requires platform interoperability. China’s regulatory approach differs. The government has pushed tech giants on monopolistic behavior. Alibaba paid a record $2.8 billion fine in 2021. But the focus is platform responsibility and data security, not necessarily API openness. This gives incumbents like WeChat regulatory cover to maintain ecosystem boundaries.

Third, timing creates asymmetric pressures. Challengers must move early to test new models before phone makers or incumbents lock down the AI layer. Platforms can afford to observe and wait–but only to a point. If edge-side AI matures faster than expected, or if phone OS manufacturers successfully integrate AI below the app layer, even super apps could find themselves bypassed. The window is not infinite for anyone. Still, the timing advantage currently favors those who control existing distribution.

Who benefits from this structure? Mini-program developers maintain their existing distribution advantages. WeChat strengthens its position as infrastructure. Users gain AI capabilities without switching platforms. The model preserves existing relationships while adding new features.

Who faces pressure? Phone makers attempting their own AI integration face the same resistance from super apps. ByteDance and other challengers must either negotiate access terms or accept limited functionality. Hardware manufacturers trying to differentiate through AI capabilities discover that software platforms still control the chokepoints.

The pattern extends beyond AI agents. This dynamic explains persistent features of China’s internet competition. Douyin couldn’t displace WeChat in social networking despite massive user growth. Alipay couldn’t overtake WeChat Pay in social payments despite superior financial technology. Platform power in China operates through ecosystem lock-in combined with regulatory relationships. Technical innovation alone rarely shifts these structures.

One question remains unresolved. Can edge-side AI eventually bypass platform control entirely? If AI runs locally on devices with sufficient capability, users might not need super apps to mediate their intent. But that future requires both technical maturation and regulatory acceptance. Neither is guaranteed.

Where Structural Advantages Meet Uncertain Futures

ByteDance kicked open the door to mobile AI agents with genuine technical achievement. But doors matter less when someone else owns the building. The company demonstrated what’s possible at the OS level. It also revealed the harsh reality of platform power.

This sequence teaches fundamental lessons. First-mover advantage means little without ecosystem access. Technical breakthroughs can be neutralized by platform control. Innovation that requires competitor cooperation faces structural barriers that cannot be solved through engineering alone.

WeChat faces real constraints around safety, compliance, and timing. These are choices the company must navigate carefully. But they represent strategic considerations, not fundamental weaknesses. The platform already serves 1.4 billion users across payments, government services, healthcare, and public infrastructure. Adding AI capabilities means accepting additional responsibility. That burden is manageable for an incumbent. It’s nearly impossible for a challenger.

Martin Lau’s statement captures this positioning. WeChat will launch an agent. The company just hasn’t decided when. That patience reflects control over current terrain–but not immunity to future disruption.

The question isn’t whether WeChat’s ecosystem advantages are real. They clearly are. The question is whether those advantages prove decisive as the AI paradigm matures, or whether alternative approaches can establish footholds before existing boundaries fully harden.

Platform power creates formidable barriers. ByteDance’s experiment demonstrated how quickly those barriers assert themselves. But it also forced the question into the open. The agent race in China will be shaped by ecosystem control, regulatory frameworks, and technical maturation. Which factor ultimately proves determinative remains to be seen.

For now, in China’s platform economy, the company with the ecosystem writes the rules. The open question is how long that remains true. For readers interested in the strategic calculations behind ByteDance’s approach, the specific technical tradeoffs, and the dynamics that will determine whether this gambit can succeed, I’ve examined these questions in depth here.