The New Interface War: Why ByteDance Had to Launch an Agent No Platform Would Approve

When APIs are closed, only forbidden paths remain. ByteDance chose one.

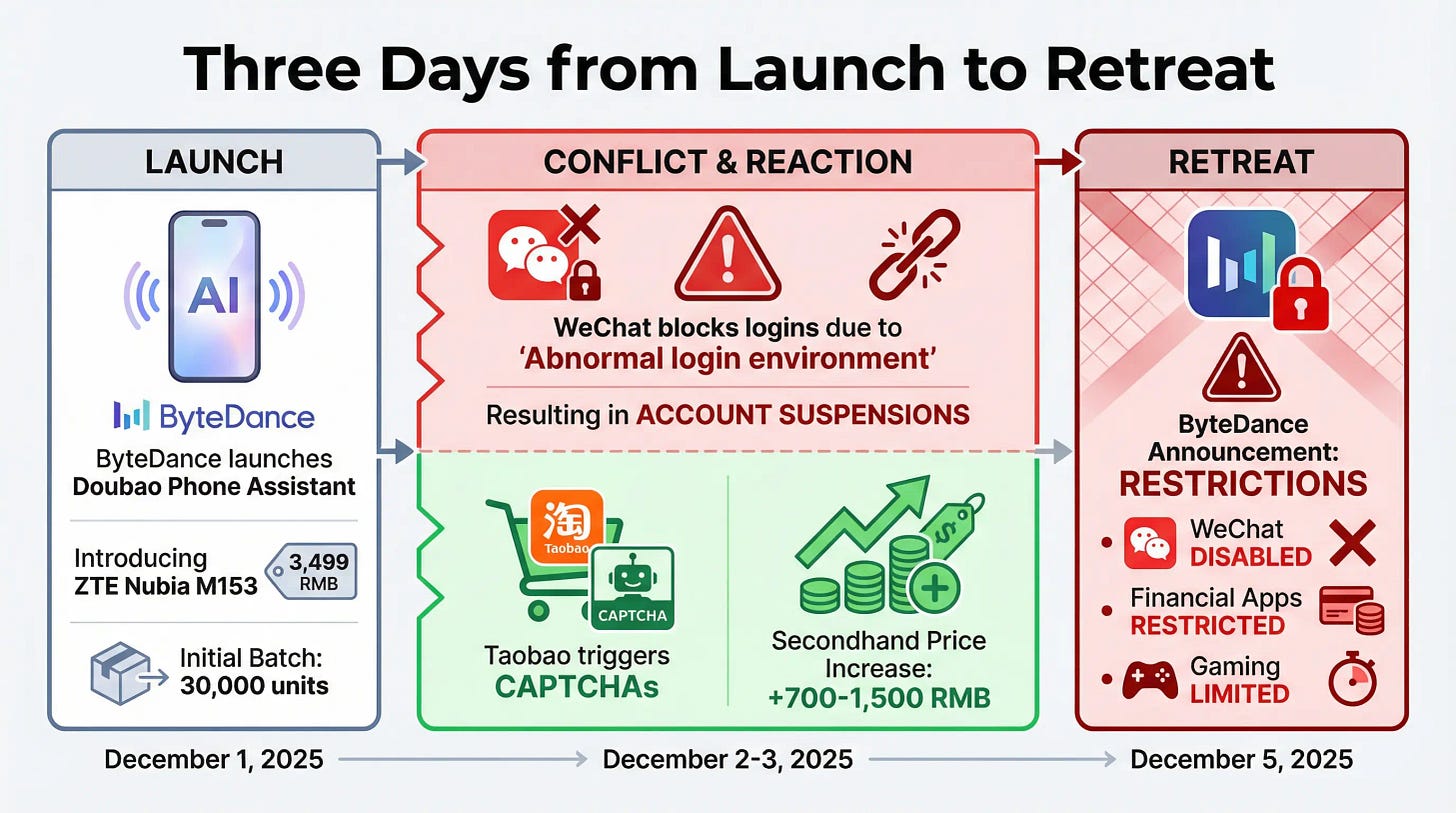

On December 1, ByteDance launched Doubao Phone Assistant, an AI agent embedded in ZTE’s Nubia M153 smartphone. The product lets users issue voice commands to accomplish tasks across multiple apps. Tell it to find the cheapest latte across three delivery platforms, and it will open each app, search for coffee, compare prices, and place an order.

Within three days, the product hit resistance. WeChat flagged logins as suspicious and forced users to log out. Users who tried alternative accounts got logged out again mid-session. Taobao triggered CAPTCHA verifications. ByteDance quickly disabled WeChat functionality and announced restrictions on financial apps and certain gaming scenarios. The company said it needed to make adjustments so that “technology development, industry acceptance, and user experience could better align.”

The rapid retreat raises a question. Why would ByteDance launch a product that immediately threatens the super apps it needs to work with? The technical approach offers a clue. Doubao Phone Assistant doesn’t integrate with apps through official APIs. Instead, it uses system-level permissions to simulate human finger taps. It reads the screen, interprets what it sees, and clicks buttons like a person would. This method is slower and clumsier than API integration. According to user tests reported by Chinese tech media outlet Chaoping, Doubao takes about 30 seconds to complete a simple check-in task on JD.com that a human could finish in 10 seconds.

The choice seems puzzling. API integration is cleaner, faster, and more reliable. So why choose the harder path?

The API Path Is Closed

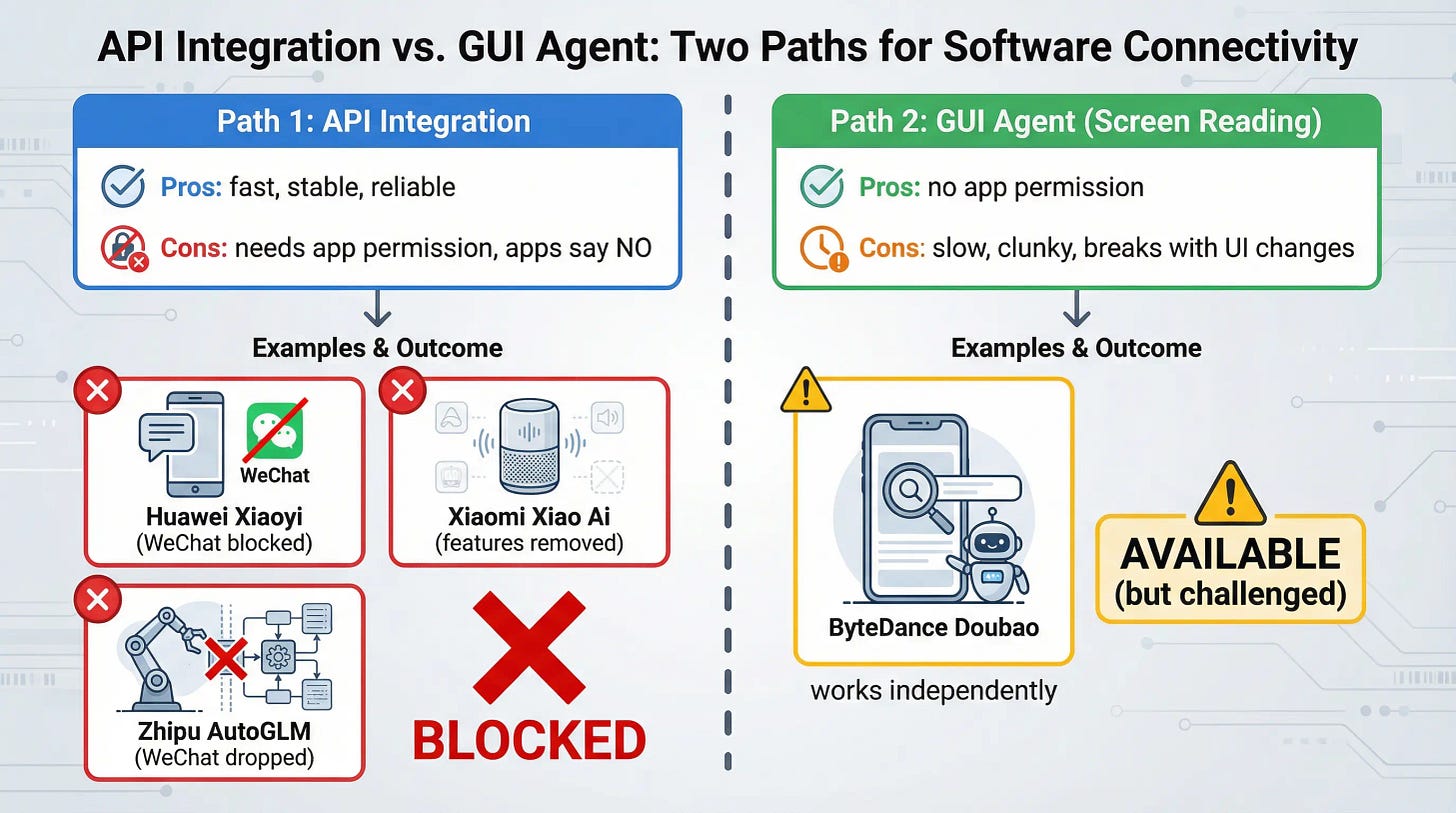

ByteDance faces a strategic choice that every AI agent builder confronts. There are two ways to make an agent operate across multiple apps.

The first path is API cooperation. The agent maker partners with app developers. Each app exposes specific functions through official interfaces. The agent calls these interfaces to complete tasks. This approach is technically superior. It’s fast, stable, and doesn’t require screen reading. But it has one fatal flaw. It requires the app owner’s permission.

Recent examples show how limited this path is. Huawei and Xiaomi both integrated AI assistants into their operating systems and attempted WeChat interaction features. Users reported these capabilities were quietly removed. Zhipu AI demonstrated AutoGLM sending WeChat red packets on stage in 2024, but by mid-2025 WeChat was no longer supported. Companies simply could not secure authorization.

WeChat’s terms make the stance explicit: it prohibits third-party software from operating accounts, controlling components, or accessing local data. In April 2025, its security team warned against tools that read chat records. Other super apps maintain similar boundaries. Their business models depend on controlling how users interact with services. Allowing an AI layer to redirect that interaction threatens their core value proposition.

This leaves the second path. The GUI Agent approach. Instead of asking for API access, the agent operates at the operating system level. It gains permission to read whatever appears on screen and simulate touch inputs. From the phone’s perspective, the agent is just another user tapping and swiping. No app-specific integration required.

ByteDance chose this path. To make it work, the company needed deep cooperation from a phone manufacturer. The key enabler is a system permission called INJECT_EVENTS. This is a signature-level permission in Android’s hierarchy. Only apps signed with the phone manufacturer’s private key can obtain it. According to technical experts cited in Chinese business media, this permission allows an app to become part of the operating system itself. It can inject simulated touch events that other apps cannot distinguish from real user input.

Mainstream phone brands won’t grant this permission to outside parties. They want to control the AI operating system layer themselves. Xiaomi has its “Super Xiao Ai.” Huawei has built its “Xiaoyi” into HarmonyOS, including an Agent-to-Agent framework that lets multiple AI agents collaborate on screen simultaneously. Vivo has its “Blue Heart Intelligence.” These companies see the AI layer as the next battleground for user control. They’re not about to hand that control to ByteDance.

This explains why ByteDance partnered with ZTE. ZTE’s Nubia brand occupies a marginal position in China’s smartphone market. The company isn’t in a position to dictate terms. For ByteDance, this partnership represents the only available path to system-level access. According to reporting by Chinese business outlet Yicai, industry insiders say “the phone is basically developed by ByteDance itself, with ZTE essentially acting as a contract manufacturer.”

The first batch included only 30,000 units. Compare this to mainstream flagships, which typically prepare 2 to 3 million units for launch. ByteDance clearly isn’t trying to compete in the smartphone market. It’s testing whether the GUI Agent approach can work at all.

The Real Battle

The super apps’ rapid response reveals what this fight is really about. This isn’t a technical dispute about APIs versus screen reading. It’s a power struggle over who controls the mobile internet’s architecture.