China’s Bet on Brain Implants: Can Policy Outrun Science?

China is racing ahead in clinical trials, but the talent math still breaks.

A paralyzed patient in Shanghai played computer games in May 2025 using only his thoughts. The procedure happened at Fudan University’s Huashan Hospital, performed by Shanghai StairMed Technology. A coin-sized wireless implant in his brain translated neural signals into commands. The technology looked similar to Neuralink’s. The timeline was remarkable. StairMed completed this first Chinese trial just 14 months after Elon Musk’s company performed its first human implant in the United States.

The speed impressed observers. The fundamentals did not. Gao Xiaorong, a Tsinghua University professor who has tracked the field for two decades, revealed a stark number. China has produced 168 doctoral graduates in brain-computer interfaces over 22 years. That’s roughly eight PhDs per year. Beijing’s target is two to three world-leading companies by 2030.

The numbers don’t add up. But Beijing is betting they don’t need to. Chinese BCI companies raised over RMB 5 billion ($700 million) in 28 funding rounds from January through November 2025. StairMed’s RMB 350 million ($49 million) round in February set a domestic record. In March, China’s national medical insurance administration created a reimbursement category for brain implant surgeries. Most countries wait until a technology proves itself before offering insurance coverage. China moved preemptively.

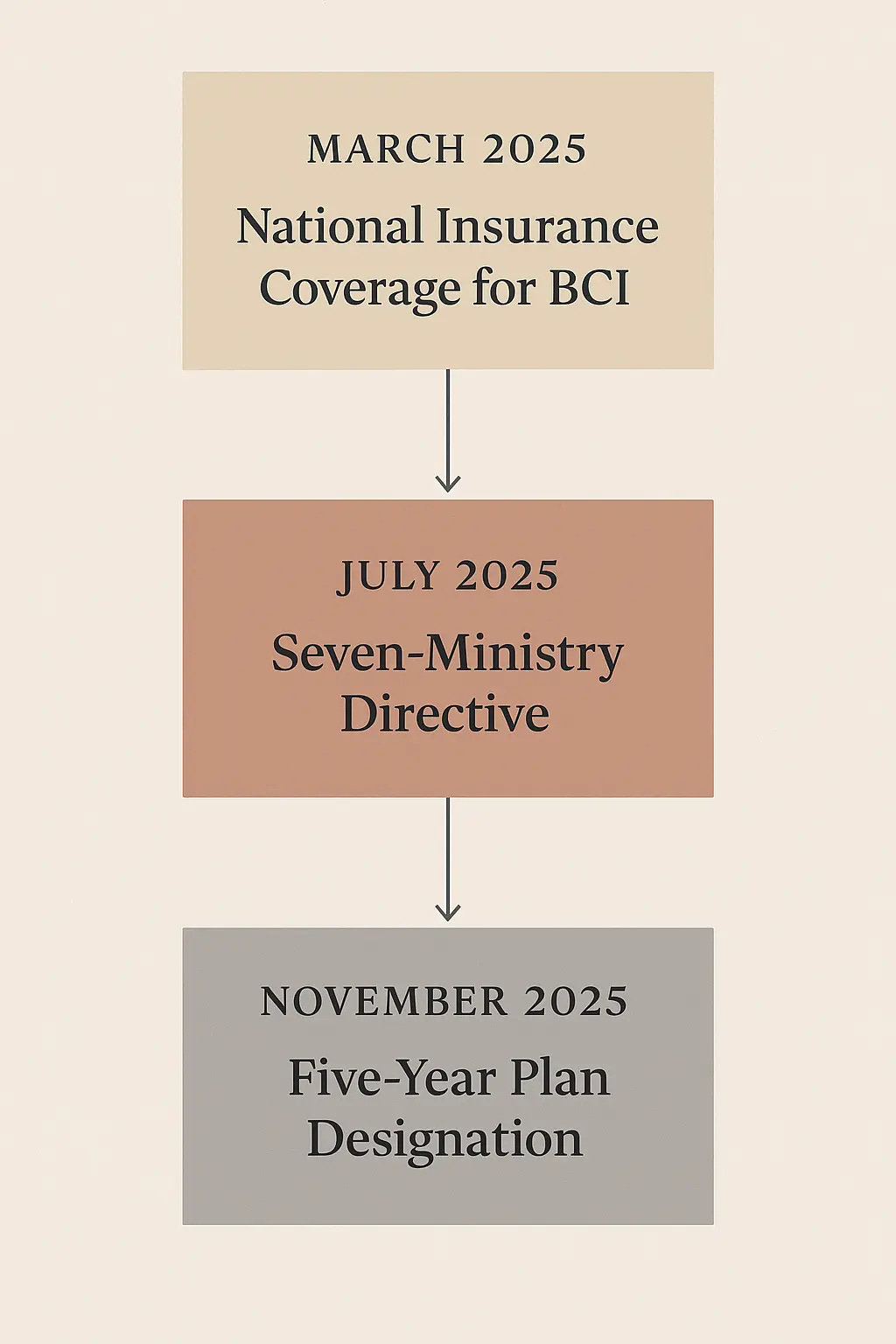

In July, seven government ministries issued a rare joint directive elevating brain-computer interfaces to national strategic priority. In November, the government’s five-year economic blueprint designated BCI as one of six “future industries” warranting major state support.

Here is the core bet: State coordination can substitute for scientific depth, at least temporarily. Insurance coverage, regulatory fast-tracking, and industrial clustering can compress development timelines enough to build the talent base China currently lacks. Whether this works will determine more than who leads in brain implants. It will test whether some types of scientific expertise can be accelerated through policy, or whether certain capabilities simply require time that cannot be compressed.

Speed Over Depth: Redefining the Game

The investment community saw the shift first. Jiang Donghui manages investments at Legend Capital, one of China’s largest venture firms. Two years ago, he evaluated BCI startups primarily on technical sophistication. Did they have novel electrode designs? Superior signal processing algorithms? Breakthrough materials?

By 2025, those questions mattered less. As Jiang put it:

We now look for clinical feasibility, clear commercialization pathways, strong execution teams, and demonstrable market traction.

Technical excellence alone does not drive funding decisions anymore.

This reflects a strategic pivot. The traditional moats in brain-computer interfaces were clear: decades of NIH-funded research, deep talent pools, technical accumulation in electrode fabrication and neural decoding. The United States built these advantages through sustained funding that began in the 1990s and accelerated with the $6 billion BRAIN Initiative launched in 2013.

China is redefining competitive advantage. The new dimensions are clinical trial velocity, regulatory efficiency, insurance integration, and industrial coordination. Consider the sequence. March 2025 brought insurance coverage for BCI procedures before any product received approval. This signals the state will absorb commercial risk. July brought the seven-ministry directive. In China’s system, joint ministerial action means top-level political backing. Resources will flow. November brought inclusion in the five-year plan, guaranteeing sustained funding through 2030.

Local governments are competing aggressively. Shanghai’s Minhang District offers up to RMB 20 million ($2.8 million) for leading BCI firms, plus subsidies for R&D, facilities, and talent recruitment. Rent is subsidized at 100 percent for the first year, declining over three years.

Liu Bing founded Mingshi Brain-Computer, a Suzhou-based company working on visual reconstruction for blind patients. He described 2025 as a turning point for the industry:

2025 was the year when Chinese BCI shifted from technical exploration to proving clinical value.

The phrasing sounds technical. The meaning is commercial. Companies no longer need the most advanced technology. They need technology that can navigate trials, gain approval, and achieve reimbursement faster than competitors.

The physical infrastructure reinforces this logic. Brain-Smart World(脑智天地), an industrial park in Shanghai, houses over 16 BCI companies in one building complex. Mingshi Brain-Computer, Lingxi Cloud, and Boda Medical occupy different floors. Huashan Hospital established an on-site consulting clinic. Companies access regulatory expertise, ethics approval guidance, and clinical trial design support without leaving the building. The setup eliminates coordination friction entirely.

The DeepSeek parallel appears compelling. The Chinese AI lab demonstrated in early 2025 that sophisticated language models could be built at a fraction of Silicon Valley’s costs through optimized training and different assumptions about computational requirements. China is attempting something similar in BCI: execution speed and coordinated support offsetting talent deficits.