DeepSeek V3.2 And The Sanctions Paradox

How Compute Scarcity Forced China To Rewrite The AI Stack.

Washington has treated advanced GPUs as the master switch for Chinese AI. Control the flow of Nvidia class accelerators, the thinking goes, and you determine how far Chinese models can climb. That theory assumes a direct line from hardware volume to model capability.

DeepSeek V3.2 quietly breaks that line.

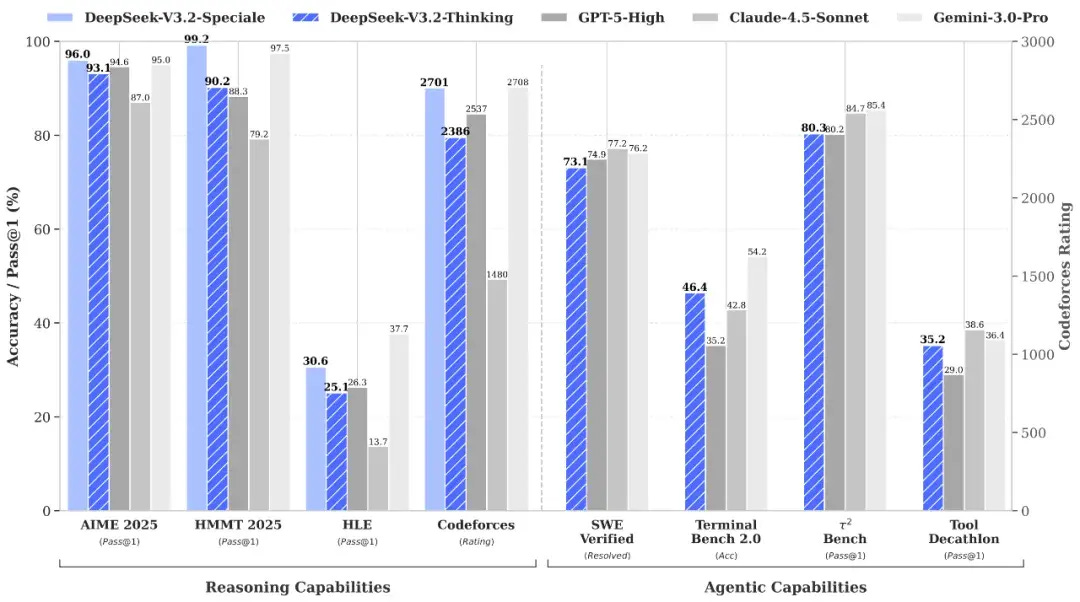

On December 1, 2025, the company released two new open models, DeepSeek-V3.2 and DeepSeek-V3.2-Speciale. The standard model reaches GPT-5 level on public reasoning benchmarks and competes with leading proprietary systems in code and math. The long-thinking Speciale variant pushes into Gemini 3 Pro territory, including gold medal level performance on IMO 2025, CMO 2025, IOI 2025 and a second place finish at the ICPC World Finals 2025.

None of this came from outspending American labs on GPUs. DeepSeek’s technical report concedes that its total training FLOPs are lower and that its world knowledge is narrower than frontier closed models. What changed is where the company put its compute and how it restructured the model to survive in a world where hardware is a constraint, not a commodity.

The result is a kind of sanctions boomerang. Export controls were meant to slow Chinese progress by limiting access to H-class chips. Instead, at least for one team, they accelerated work on architectures and training schemes that reduce dependence on brute force. The contest is no longer only about who has more GPUs. It is about who can create more intelligence per unit of compute.

This is the real significance of DeepSeek V3.2: it turns hardware scarcity into an architectural pressure, and that pressure is now visible in the design of the model.

From Hardware Containment To Architectural Competition

To understand why V3.2 matters, you have to start from the baseline the DeepSeek team itself describes. In their technical introduction they note that in recent months, open models have not been closing the gap with closed ones. The opposite was happening. Proprietary systems were improving faster, especially on complex reasoning and agent tasks.

They identify three structural weaknesses in most open models:

Full attention over long sequences makes long context expensive and slow.

Post-training receives very little compute compared with pre-training.

Agent behavior and tool-using generalization lag far behind closed models.

DeepSeek’s answer is not “train a bigger base model later when we can.” Instead, they deliberately optimize exactly those three weak points. The architectural work happens where sanctions hurt most: in long context, in how compute is allocated, and in the agent layer that will matter most for production use.

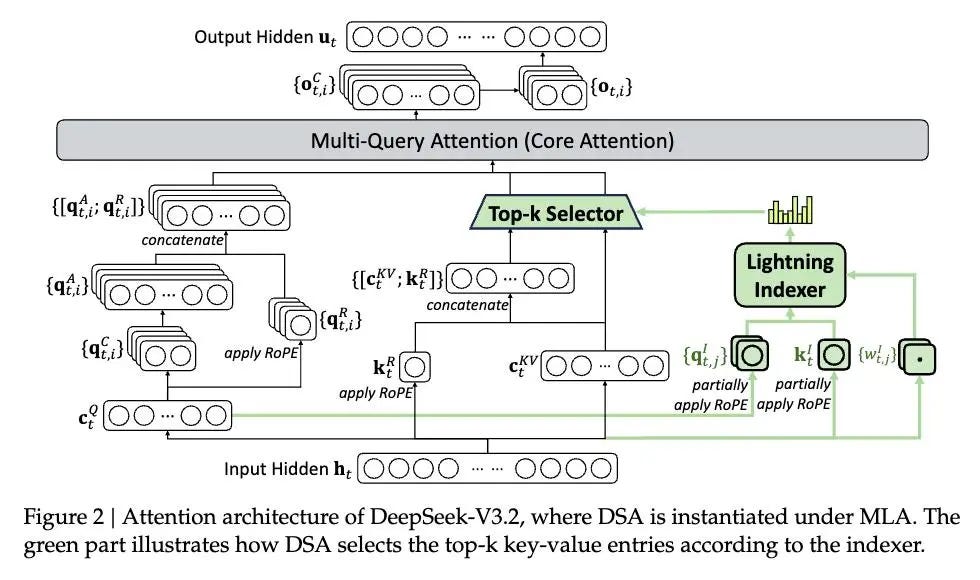

The first pillar is DeepSeek Sparse Attention.

DSA: Turning Long Context Into A Cheap Resource

Traditional attention treats every new token as a potential interaction with every earlier token. Complexity grows with the square of sequence length. That is manageable for 4K or 8K contexts on large clusters; it becomes toxic at 128K context lengths when you are counting GPUs.

DeepSeek’s answer is DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA). Instead of asking the model to attend to everything, they insert a “lightning indexer” that scores the past and selects only a small subset of tokens that matter. These indexer heads are few in number and can run in FP8, so they add little overhead. The heavy attention operation is then run only on the chosen tokens.

The training procedure is conservative. V3.2 starts from DeepSeek-V3.1-Terminus, which already supports 128K context. In a first “dense warmup” phase, the full attention structure is preserved and only the indexer is trained to imitate the old attention distribution. In a second phase, sparsity is gradually introduced and the entire model is optimized.

The result is a model that keeps or slightly improves benchmark quality compared to V3.1, while cutting long-context cost to near linear in sequence length. In long-context benchmarks like Fiction.liveBench and AA-LCR, V3.2 performs at least as well as the dense baseline while being significantly more efficient.

For a hardware constrained team, that is not just an optimization. It is a redefinition of what “context” means economically. If context becomes cheap, you can afford to spend compute somewhere else.

That ‘somewhere else’ turns out to be the most consequential shift in DeepSeek’s strategy — and potentially the most overlooked by Western competitors. Understanding where DeepSeek redirected its compute budget reveals not just how they closed the performance gap, but why this approach might be harder to counter than hardware restrictions alone.