Xiaomi’s EV Edge: When Platform Cash Fuels Manufacturing

Why losing 6,000 yuan per car isn't a bug, but a feature of a powerful ecosystem strategy.

Hello China Tech by Poe Zhao – Weekly insights into China’s tech revolution. I analyze how developments in Chinese AI, electric vehicles, robotics, and semiconductors are reshaping global technology landscapes. Each piece contextualizes China’s innovations within worldwide market dynamics and strategic implications.

Limited-time offer: Upgrade to premium for 3x weekly strategic insights and market analysis. Regular pricing is $15/month, but subscribe before September 1st to lock in permanent discount pricing at just $10/month or $100/year.

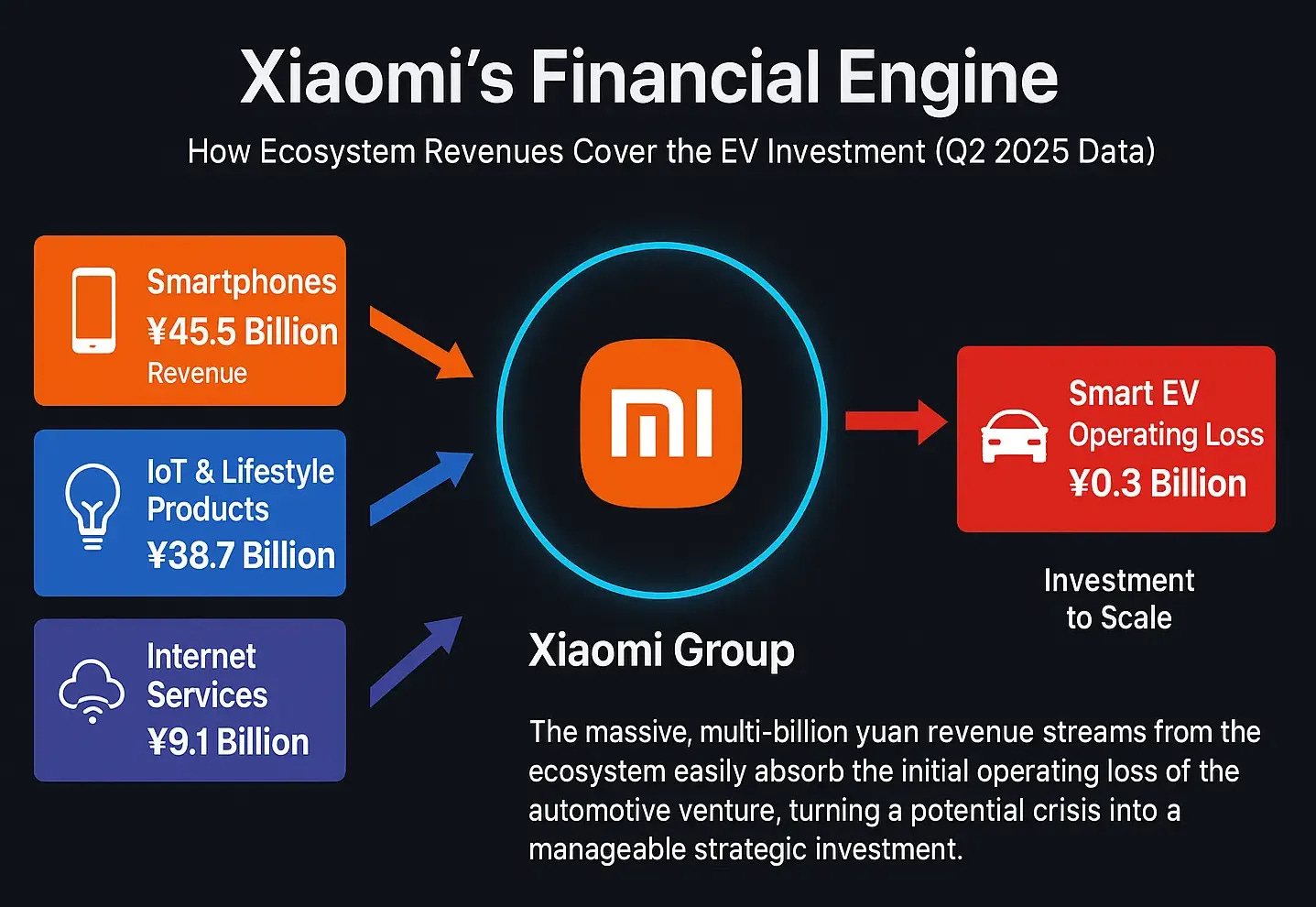

In the brutal landscape of China’s electric vehicle market, where established players burn billions chasing profitability and startups collapse under the weight of capital demands, one company stands tantalizingly close to an achievement that has eluded most of its peers: breaking even. Xiaomi, the smartphone giant turned automotive newcomer, reported a mere 300 million yuan operating loss in Q2 2025—a figure that translates to just 6,000 yuan per vehicle sold. For context, that’s less than what most consumers spend on a high-end smartphone.

This proximity to profitability after barely 18 months in the market represents more than just efficient execution; it signals the emergence of a fundamentally different approach to automotive competition. While traditional automakers and even Tesla built their businesses around the assumption that cars must eventually pay for themselves, Xiaomi has pioneered what might be called “platform-subsidized manufacturing”—using the cash flows from IoT devices and internet services to underwrite its automotive ambitions.

The implications extend far beyond one company’s financial engineering. Xiaomi’s model offers a compelling framework for understanding how platform companies might successfully enter capital-intensive industries, how ecosystem thinking can reshape competitive dynamics, and why the next wave of automotive innovation might come not from traditional car companies, but from technology platforms with diversified revenue streams.

The Economics of Ecosystem Leverage

To understand Xiaomi’s approach, consider the traditional economics of automotive manufacturing. Most EV startups follow a familiar pattern: raise capital, develop technology, build manufacturing capacity, then pray that vehicle sales eventually cover the enormous fixed costs of R&D, manufacturing, and operations. This linear path to profitability has claimed casualties from Fisker to countless Chinese startups.

Xiaomi’s path looks different. In Q2 2025, while the automotive division lost 300 million yuan, the company’s IoT business generated approximately 8.7 billion yuan in gross profit, and internet services contributed another 6.9 billion yuan. The smartphone business, despite facing headwinds, still produced 5.2 billion yuan in gross profit. In essence, Xiaomi’s automotive business operates within an ecosystem that generates over 20 billion yuan in quarterly gross profit from other activities.

This “family-feeding” model—where established business lines subsidize new ventures—isn’t entirely novel. Amazon famously used its retail profits to fund AWS development, and Google leveraged search advertising revenue to explore everything from autonomous vehicles to quantum computing. But Xiaomi’s application to automotive manufacturing represents perhaps the most systematic and transparent example of cross-business subsidization in a capital-intensive industry.

The model’s power lies in its risk distribution. Traditional automakers must bet their entire enterprise on automotive success. EV startups face an even starker binary outcome: achieve scale and profitability, or cease to exist. Xiaomi, by contrast, can afford to lose money on cars for years while its ecosystem businesses provide the financial buffer needed to achieve manufacturing scale and operational efficiency.

Consider the unit economics. With gross profit of 67,000 yuan per vehicle and allocated operating expenses of approximately 73,000 yuan per unit, Xiaomi needs to either reduce per-unit costs by 6,000 yuan or increase per-unit profits by the same amount to reach break-even. For a company manufacturing complex consumer electronics at scale, this represents an engineering challenge rather than an existential crisis.

The Hidden Architecture of Platform Advantage

The financial subsidization is only the most visible layer of Xiaomi’s platform advantage. Deeper structural benefits emerge from what might be called “capability arbitrage”—the ability to apply skills and resources developed in one domain to adjacent markets.

Xiaomi’s automotive R&D spending of 7.8 billion yuan in Q2 doesn’t represent purely incremental investment. Much of this research serves dual purposes. The company’s AI algorithms improve both smartphone cameras and automotive driver assistance systems. Its supply chain relationships with battery manufacturers support both smartphones and EVs. Its software development capabilities enhance user experiences across devices and vehicles simultaneously.

图/生态(An automotive assembly line, one half with physical robotic arms and car parts, the other half is made of flowing digital code and UI elements, seamlessly merging in the middle to form a complete car, futuristic, software-defined manufacturing concept.)

This shared infrastructure creates a fundamental cost advantage over pure-play automotive companies. When NIO or XPeng invest in AI development, those costs must be absorbed entirely by automotive revenues. When Xiaomi makes similar investments, the costs are distributed across multiple revenue streams while the benefits compound across multiple product categories.

The ecosystem effects extend to market positioning as well. Xiaomi’s brand promise of “premium technology at accessible prices” translates seamlessly from smartphones to automobiles. The company’s retail infrastructure—nearly 15,000 offline stores in mainland China as of Dec 31, 2024, with management targeting ~20,000 by end-2025 and roughly 1,700 net adds in Q2 2025—provides automotive showroom capacity without significant incremental real-estate costs. Its customer base of loyal smartphone and IoT device users represents a pre-qualified automotive prospect pool.

Perhaps most importantly, Xiaomi’s ecosystem approach allows for patient capital deployment. While automotive startups face quarterly investor scrutiny focused solely on vehicle metrics, Xiaomi’s investors evaluate the company’s performance across its entire business portfolio. This creates breathing room for longer-term strategic investments in automotive technology and market development.

The Limits and Risks of Cross-Subsidization

The platform advantage, however powerful, is not without constraints and risks. The most obvious limitation is scale dependency. Xiaomi’s ability to subsidize automotive losses depends on maintaining profitable growth in its core businesses. The company’s smartphone revenue declined 2.1% year-over-year in Q2 2025, while average selling prices dropped 11.3% quarter-over-quarter. If these trends continue, the financial foundation supporting automotive expansion could weaken.

The IoT business, while currently growing at 44.7% annually, faces intensifying competition from traditional appliance manufacturers like Gree and Midea, who are responding aggressively to Xiaomi’s incursion into their territories. Success in automotive markets cannot come at the expense of competitiveness in core businesses—a balancing act that requires sophisticated resource allocation.

There are also strategic risks inherent in cross-business subsidization. The automotive industry’s capital intensity could eventually overwhelm even a diversified platform. If Xiaomi’s automotive ambitions expand beyond its current two-model strategy to compete across multiple vehicle categories, the financial demands could strain the entire ecosystem. The company’s announcement of European market entry by 2027 suggests exactly this kind of ambitious expansion.

Regulatory risks add another layer of complexity. Xiaomi’s automotive business benefits from China’s supportive EV policies, but international expansion will expose the company to different regulatory environments. The 48% tariff burden in Europemeans Xiaomi’s cost advantages may not translate to competitive pricing in international markets, potentially requiring even greater subsidization to achieve market penetration.

The Template for Platform-Manufacturing Convergence

Xiaomi’s early success illuminates something more profound than one company’s clever financial engineering—it reveals how the boundaries between platform businesses and manufacturing industries are dissolving in the digital age. This convergence is not accidental but reflects fundamental changes in how value is created in technology-intensive industries.

The traditional separation between “asset-light” platform businesses and “asset-heavy” manufacturing assumed that these models required fundamentally different capabilities, risk profiles, and investor expectations. Xiaomi’s automotive venture demonstrates that this separation may be increasingly artificial. When manufacturing becomes software-defined—as it has in electric vehicles—the distinction between platform operations and physical production blurs significantly.

Consider how Xiaomi’s automotive factory reflects this convergence. According to a company video and press materials, the Beijing facility can produce a car roughly every 76 seconds under optimized conditions, with extensive automation across key processes.The factory’s operations are software-controlled, data-optimized, and designed for the kind of rapid iteration cycles familiar in consumer electronics. This isn’t just automotive manufacturing with some digital tools—it’s platform thinking applied to physical production.

The success of this model depends on several conditions that are becoming increasingly common across manufacturing industries. First, the product must be sufficiently software-defined that traditional manufacturing expertise becomes less critical than system integration and user experience design. Second, the supply chain must be modular enough that platform companies can leverage existing supplier relationships rather than building entirely new procurement capabilities. Third, the market must value system-level innovation over incremental improvements in traditional manufacturing metrics.

These conditions now exist across numerous manufacturing sectors beyond automotive. Consumer appliances, industrial equipment, and even aerospace are becoming increasingly software-defined. Supply chains have modularized as component manufacturers serve multiple industries. Customers increasingly value connectivity, intelligence, and ecosystem integration over purely physical product attributes.

This suggests that Xiaomi’s model might represent the leading edge of a broader transformation in manufacturing competition. Platform companies with strong positions in adjacent technology markets—semiconductor design, artificial intelligence, battery technology, or industrial automation—may find manufacturing expansion increasingly attractive as a way to capture more value from their technological capabilities.

The implications extend beyond individual company strategies to the structure of entire industries. If platform-based manufacturers can successfully compete with traditional manufacturing companies, we might expect to see industry consolidation around technology platforms rather than manufacturing assets. The competitive advantage might shift from optimizing physical production processes to optimizing the integration of physical and digital capabilities across entire ecosystems.

What to Watch: The Observable Framework

Xiaomi’s journey provides a real-time case study in platform-based market entry, but the final verdict on this model’s viability requires continued observation across several key dimensions.

Financial sustainability: Monitor whether Xiaomi’s core businesses can maintain the profitability needed to support automotive expansion. Key metrics include smartphone ASP trends, IoT market share in competitive segments, and overall ecosystem profit margins.

Scale economics: Track whether automotive unit economics improve as production volumes increase. The critical threshold appears to be around 30,000–35,000 monthly deliveries—the level needed to spread fixed costs sufficiently to achieve profitability.

Ecosystem integration: Observe how effectively Xiaomi integrates automotive products into its broader ecosystem. Success metrics include cross-selling rates between automotive and other product categories, customer lifetime value across the ecosystem, and brand coherence maintenance.

Competitive response: Watch how traditional automakers and other technology companies respond to Xiaomi’s model. Automotive companies might seek technology partnerships or ecosystem expansion, while technology companies might accelerate their own automotive ambitions.

International scalability: Xiaomi’s planned 2027 European launch will test whether the platform model works in markets without supportive industrial policy and with higher regulatory barriers.

The stakes extend beyond one company’s success or failure. Xiaomi’s experiment in platform-subsidized manufacturing could establish a new paradigm for how technology companies enter capital-intensive industries. If successful, it might encourage broader platform-based competition across manufacturing sectors. If unsuccessful, it would reinforce traditional boundaries between platform businesses and capital-intensive manufacturing.

For observers of China’s technology ecosystem, Xiaomi’s automotive venture represents something larger than corporate diversification—it’s a test of whether platform-based business models can overcome the traditional constraints of industrial capitalism. The answer will likely determine not just Xiaomi’s future, but the trajectory of technology-industry convergence in the global economy.

The proximity to profitability is compelling, but the more important question is whether Xiaomi is pioneering a sustainable model for platform companies to compete in manufacturing industries, or simply demonstrating the limitations of financial engineering in capital-intensive markets. The next twelve months should provide the answer.

This analysis provides the strategic framework. It’s the 'what' and the 'why,' and I deliver it for free every week.

But for investors and strategists, that's only half the equation. True competitive advantage comes from the 'how' and 'when'—the actionable insights that drive decisions. That’s what Premium is for.

As a Premium subscriber, you get everything else: two additional investment-focused analyses each week, quarterly deep-dive industry reports, and direct access to me for your specific questions.

To thank my founding members, I'm offering a 33% lifetime discount for a limited time. Lock in this launch pricing forever before it's gone.

This special founder's rate expires permanently on September 1st.