While Nvidia Celebrated, Huawei Built an Empire

How $4.5 billion in export restrictions accidentally accelerated China's quest for AI independence.

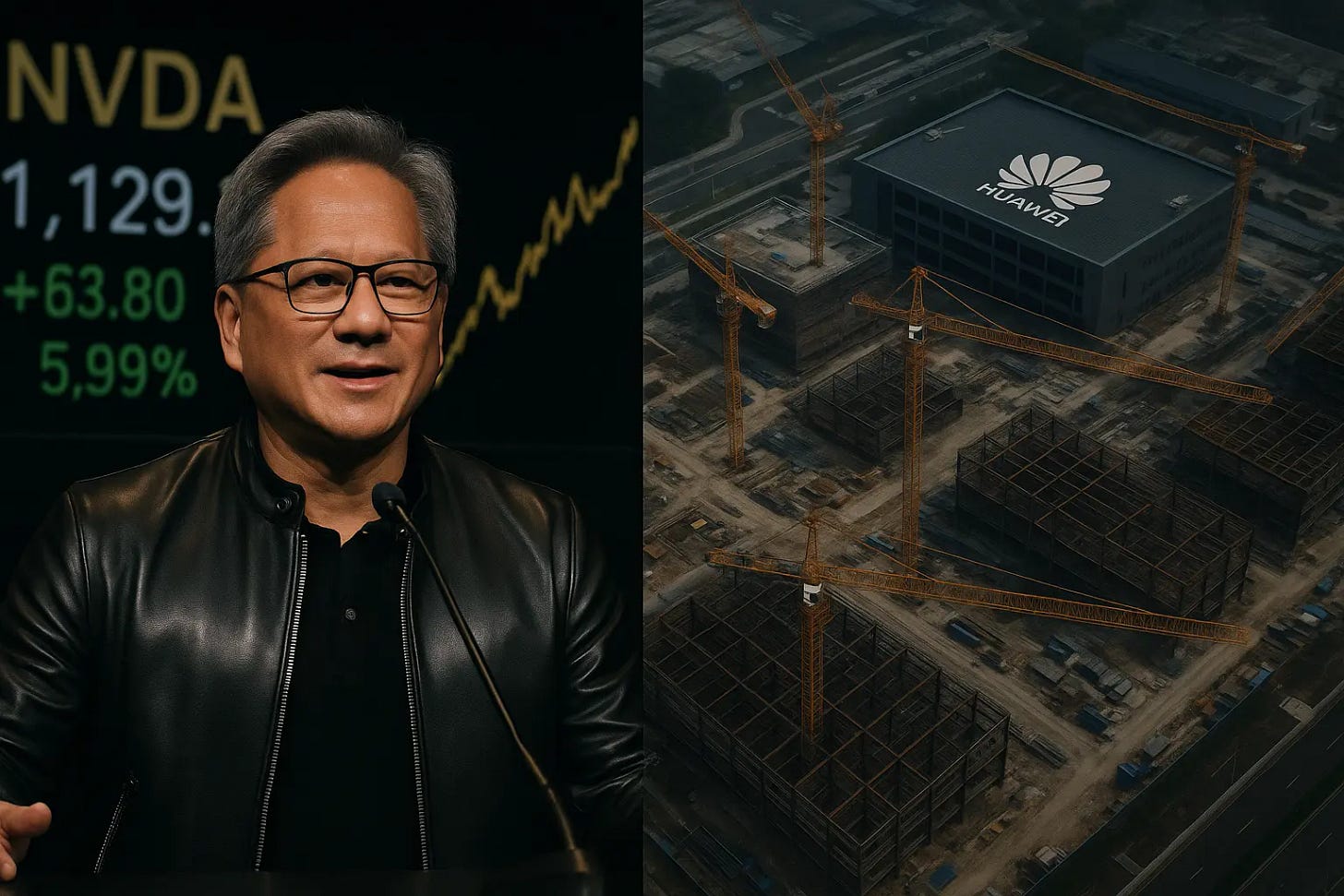

At 4:30 PM Pacific Time on May 28, Jensen Huang was fielding congratulatory questions from Wall Street analysts. Nvidia’s stock had just jumped 6% on record earnings. But 8,000 miles away in Shenzhen, satellite cameras were capturing a different story—construction cranes working around the clock on what may become the most consequential challenge to American technological dominance in decades.

Nvidia’s first quarter fiscal 2026 earnings report read like another triumphant chapter in the AI gold rush. Revenue surged to $44.06 billion—a staggering 69% increasefrom the previous year, according to the company’s official earnings release. The data center division, which powers the world’s AI infrastructure, generated $39.1 billion, accounting for 88% of total revenue and growing 73% year-over-year, CNBC reported.

Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s leather-jacket-clad CEO, painted a picture of unstoppable global demand. AI inference token generation has increased tenfold in just one year, he noted during the earnings call, describing his company’s Blackwell processors as advanced systems designed for the next wave of AI reasoning.

Yet beneath these gleaming numbers lies a story that reveals the true battle shaping AI’s future—one that threatens to split the global technology landscape in two.

The $4.5 Billion Warning Signal

Hidden within Nvidia’s earnings celebration was a jarring disclosure: a $4.5 billion inventory writedown. The culprit? New U.S. export restrictions on Nvidia’s H20 chip, specifically designed for the Chinese market. This wasn’t just a one-time hit—the company projected an additional $8 billion in lost revenue for the current quarter.

To understand the magnitude of this disruption, Reuters reported that China generated $17 billion in revenue for Nvidia in its previous fiscal year, representing 13% of total sales. According to sources familiar with the matter who spoke to Reuters, the H20 chip alone had secured $18 billion in orders since the start of 2025. In one regulatory stroke, America’s most valuable chip company lost access to what Huang characterized as a $50 billion market in China that is now effectively closed to U.S. industry, according to CNBC’s coverage of the earnings call.

The restrictions have effectively ended Nvidia’s Hopper data center business in China, Huang acknowledged to investors, his usual optimism replaced by stark recognition of a transformed competitive landscape.

This wasn’t merely a business setback—it was a strategic retreat that could reshape the global AI landscape in ways Nvidia’s soaring stock price failed to capture.

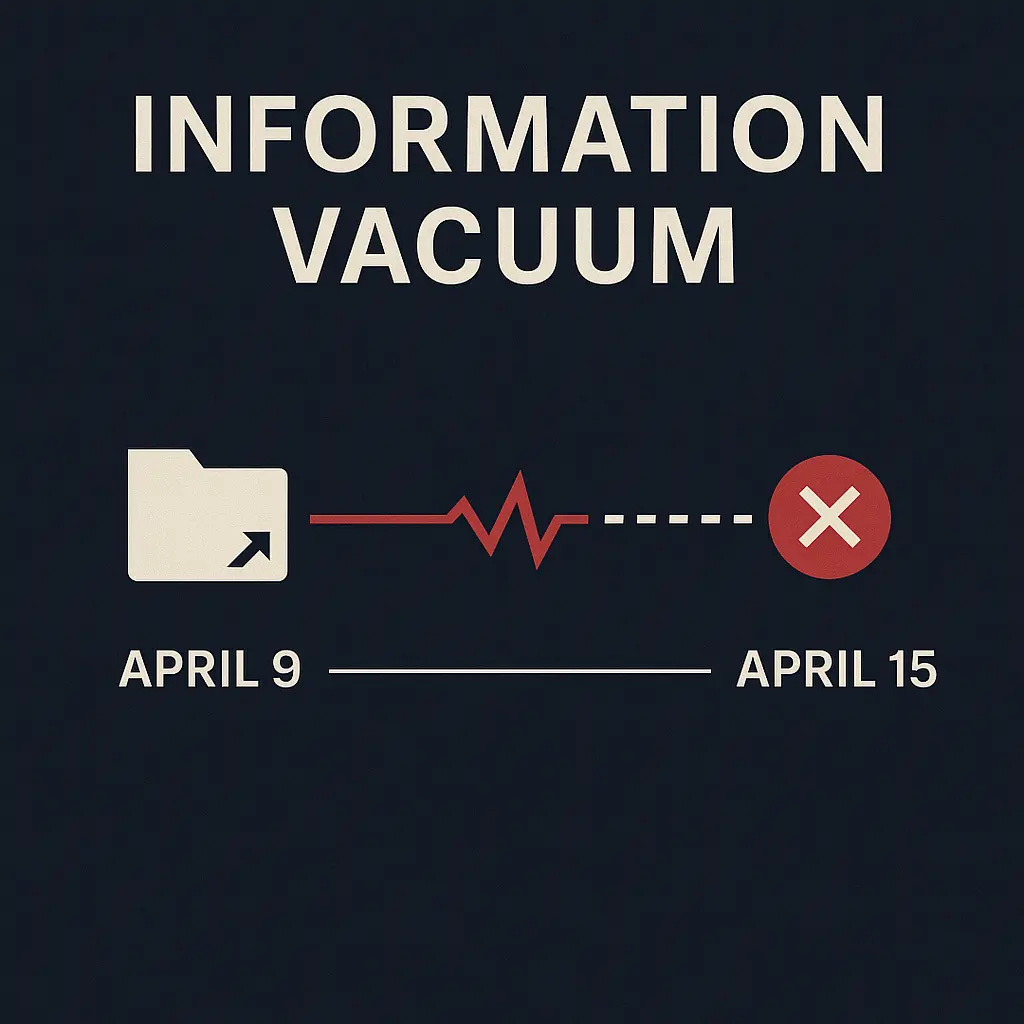

Six Days in the Information Void

The chaos surrounding the H20 restriction reveals something more troubling than immediate financial losses: the breakdown of information flows in an increasingly weaponized technology supply chain.

According to Reuters’ investigation, U.S. government officials informed Nvidia on April 9 that its H20 processor would require an export license for Chinese sales. Yet the company didn’t make this development public until April 15—a six-day information vacuum that left major stakeholders operating on false assumptions.

During this critical period, Reuters reported that major Chinese cloud companies continued anticipating H20 deliveries by year-end, unaware that their multi-billion-dollar AI infrastructure plans had just evaporated. Even more remarkably, sources familiar with the matter told Reuters that Nvidia’s own China sales team appeared uninformed about the impending restrictions.

The information asymmetry wasn’t just a communication failure—it highlighted how geopolitical risks now operate beyond traditional business risk management frameworks. In an interconnected global technology ecosystem, regulatory decisions made in Washington can instantly obsolete supply chains spanning continents, with implications cascading through markets in real-time.

Reuters had previously reported that Chinese tech giants including Tencent, Alibaba, and ByteDance had ramped up H20 orders throughout early 2025, driven by surging demand for affordable AI models from companies like DeepSeek. Within hours of Nvidia’s disclosure, Alibaba shares fell 4.1% and Tencent dropped 1.8% in Hong Kong trading.

The Shadow Empire Emerges

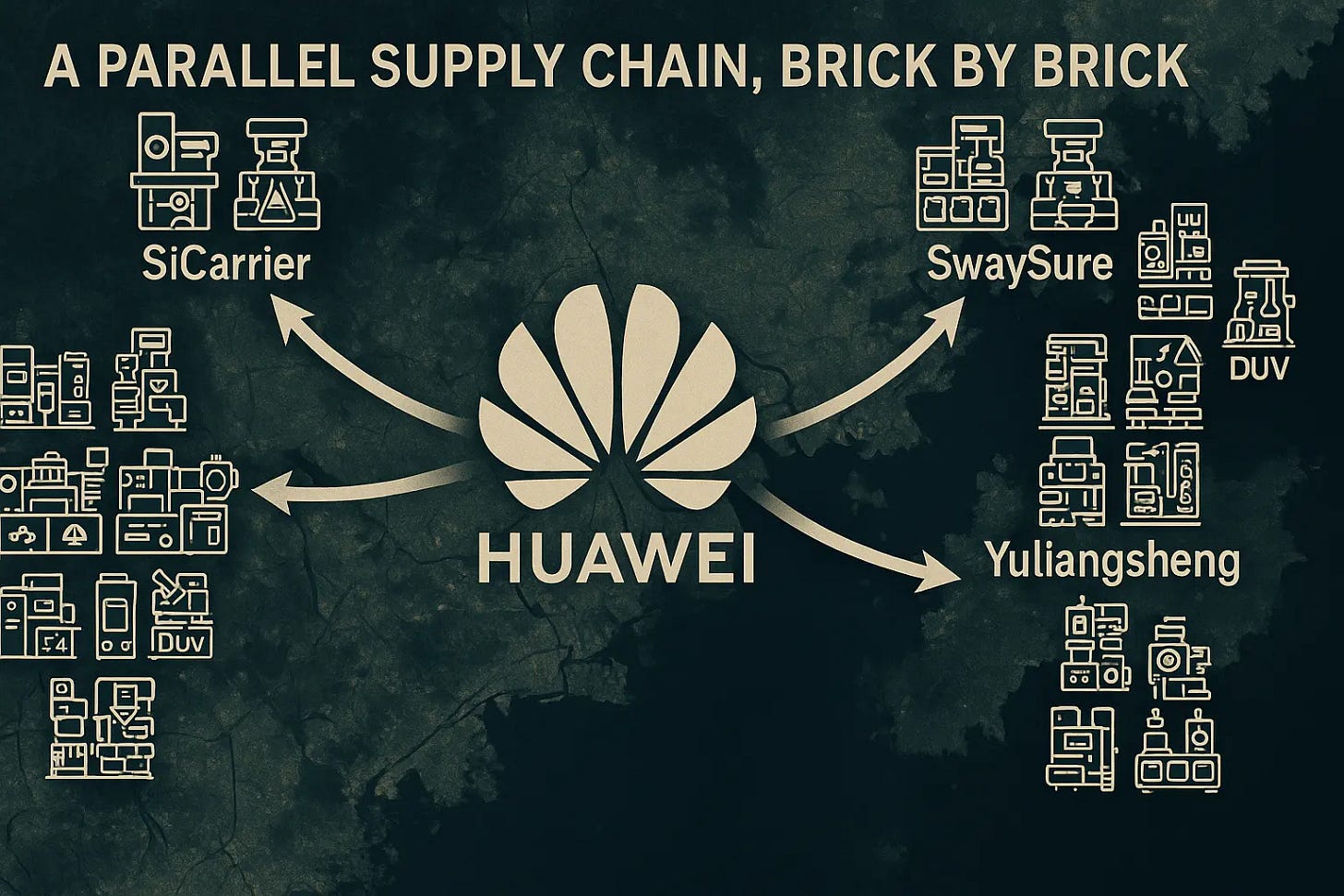

While Nvidia executives fielded analyst questions about China market losses during their earnings call, satellite imagery was revealing a parallel story unfolding 30 kilometers outside Shenzhen. In the Guanlan district, Huawei was constructing what may become the most significant challenge to American semiconductor dominance—a network of advanced chip manufacturing facilities that could redefine the global AI supply chain.

The Financial Times obtained satellite images showing three manufacturing sites built in Huawei’s distinctive architectural style, rapidly developed since construction began in 2022. According to the newspaper’s investigation, these facilities represent something unprecedented: a single company’s attempt to recreate the entire AI supply chain domestically, from wafer fabrication equipment to model building.

Dylan Patel, founder of chip consultancy SemiAnalysis, told the Financial Times that Huawei has embarked on an unprecedented effort to develop every part of the AI supply chain domestically, noting that they had never seen one company attempt to do everything before.

The first site is operated by SiCarrier, a company that the Financial Times reported emerged from a Huawei laboratory with backing from Shenzhen state funds. While Huawei officially denies connections to these “independent” startups, industry insiders described to the newspaper a sophisticated network where the tech giant provides early support through management teams, technical expertise, fundraising assistance, and technology transfers.

According to the Financial Times’ reporting, SiCarrier unveiled approximately 30 semiconductor manufacturing tools at Shanghai’s Semicon conference in March 2025, including etch, testing, and deposition equipment—direct challenges to Western suppliers. Through its subsidiary Yuliangsheng, backed by Shanghai government funds, the company is developing deep ultraviolet lithography machines that could eventually compete with Dutch giant ASML’s monopolistic position.

The second facility houses SwaySure, which the Financial Times noted supplies Huawei with memory chips for automotive and consumer electronics, targeting the market dominance of South Korea’s SK Hynix.

Most significantly, the third site is Huawei’s self-operated facility, designed to manufacture 7-nanometer smartphone processors and Ascend AI chips—the company’s first attempt at producing its own high-end semiconductors at scale, according to people familiar with the matter who spoke to the Financial Times. Construction is scheduled for completion in the coming months, though operations won’t begin for at least a year as Huawei seeks to use predominantly domestic equipment still undergoing testing.

The Performance Gap and Market Opportunity

The conventional wisdom suggests that American technological superiority provides an insurmountable moat. Current assessments indicate that Nvidia’s previous generation chips perform approximately 40% better than Huawei’s best AI processors, according to Gregory Allen, director of the Wadhwani AI Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, who spoke to The New York Times.

However, this analysis may fundamentally misunderstand how technological ecosystems evolve. The New York Times reported that Nvidia was expected to make more than $16 billion in annual H20 sales before the restrictions—revenue that doesn’t simply vanish but represents market opportunity that flows directly to domestic alternatives.

For Huawei, this revenue transfer provides something potentially more valuable than advanced chip designs: scale and customer relationships. The New York Times noted that working with leading Chinese AI companies like DeepSeek gives Huawei crucial feedback for improving both hardware performance and the software tools that have been one of Nvidia’s core competitive advantages.

Gregory Allen told The New York Times that Huawei is a ferocious competitor that brings a mixture of very high-quality talent, intensely driven work culture and the deep backing of the Chinese government.

This combination of technical ambition, market access, and state support has already produced results in other sectors. According to The New York Times’ analysis, Huawei previously surpassed European rivals Ericsson and Nokia in telecommunications equipment, and challenged Apple’s smartphone dominance before U.S. sanctions disrupted its global market access.

The Technical Infrastructure Race

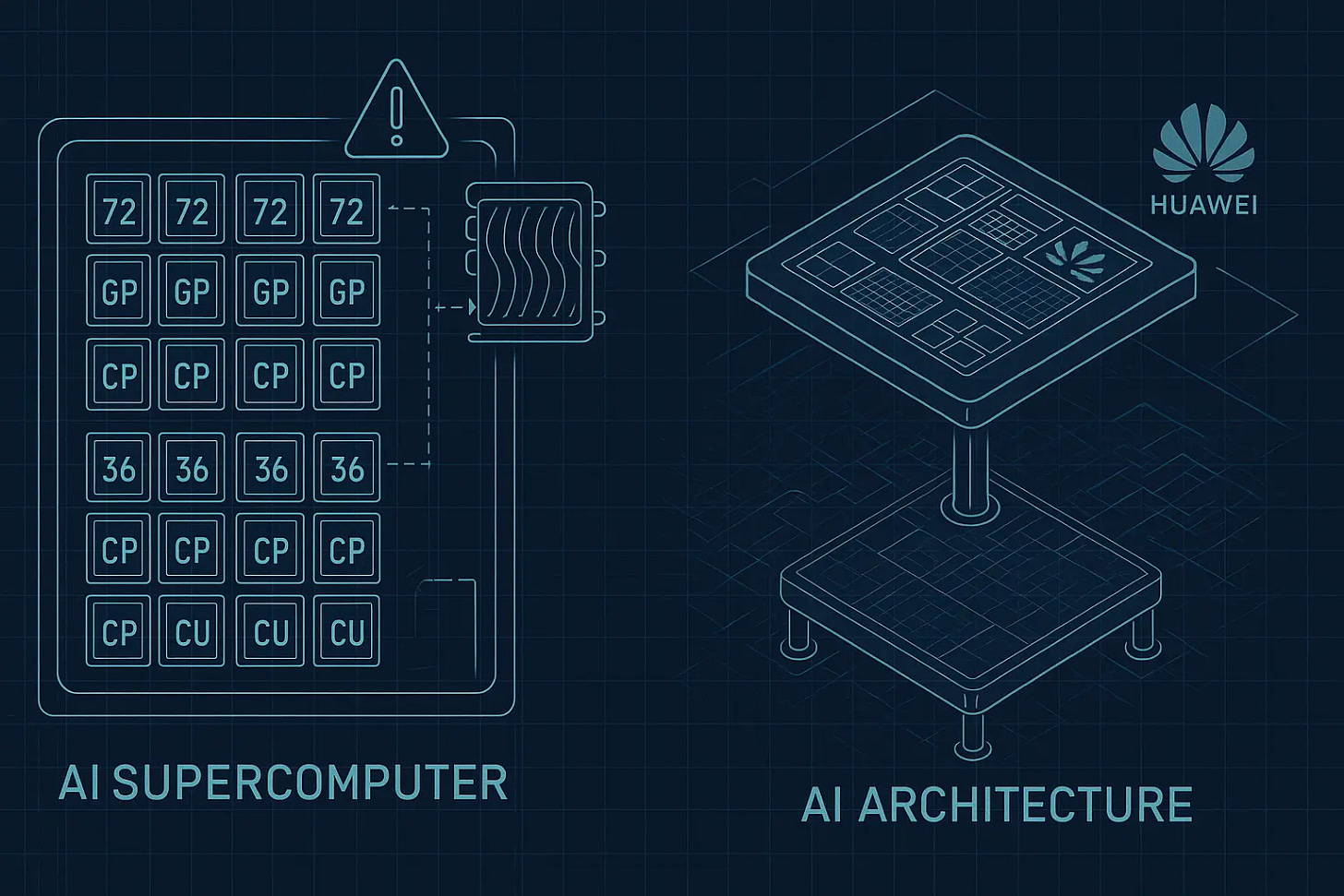

Beyond individual chip performance lies a more complex competition over AI infrastructure systems. Nvidia’s earnings report highlighted the resolution of technical problems that had plagued its flagship GB200 AI racks—complex systems containing 36 central processing units and 72 Blackwell graphics processing units connected through the company’s NVLink communication system, according to the Financial Times’ reporting.

These “AI supercomputers” had faced months of technical challenges, the Financial Times reported, including overheating from 72 high-performance GPUs, liquid cooling system leaks, software bugs, and inter-chip connectivity problems. Supply chain partners including Foxconn, Inventec, and Wistron worked intensively to resolve these issues, with the Financial Times noting that shipments finally began at the end of the first quarter.

Chu Wei-Chia, a Taipei-based analyst at consultancy SemiAnalysis, told the Financial Times that the complexity of synchronizing such large numbers of processors represented unprecedented engineering that no company had previously attempted at this scale and timeframe. VentureBeat reported that Microsoft has deployed tens of thousands of Blackwell GPUs and expects to scale to hundreds of thousands of the GB200 systems, primarily supporting its partnership with OpenAI.

This technical leadership has enabled Nvidia to maintain premium pricing, with VentureBeat noting that gross margins are expected to reach the mid-70% range by late 2025. However, the same technical complexity that creates competitive moats also creates opportunities for alternative approaches.

The Emerging Parallel Ecosystem

While American companies perfect high-margin, cutting-edge solutions, Chinese competitors are building a parallel ecosystem optimized for different priorities: self-sufficiency, cost-effectiveness, and integration with domestic AI development workflows.

This parallel development isn’t merely about catching up to American capabilities—it’s about creating alternative pathways that could eventually challenge Western technological assumptions. Chinese AI models like DeepSeek have demonstrated that innovative algorithms can sometimes achieve comparable results with less computational power, potentially reducing the performance gap that hardware limitations create.

The broader implications extend beyond chip manufacturing. According to the Financial Times’ investigation, Huawei’s facilities in Shenzhen are part of a network that includes semiconductor manufacturing investments in Shanghai, Ningbo, and Qingdao. The newspaper reported that the company has also recruited engineering teams from China’s domestic champion SMIC and equipment maker Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment (SMEE), leveraging political influence to access critical expertise even from competitors.

Global Market Realignment

The bifurcation of AI supply chains is already reshaping global market dynamics beyond the U.S.-China relationship. The Financial Times reported that Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates announced plans to acquire thousands of Blackwell chips during President Trump’s Gulf tour, as Nvidia seeks to diversify its customer base beyond Big Tech “hyperscaler” companies.

These sovereign AI purchases represent a new category of technology buyer: nation-states treating AI infrastructure as strategic assets comparable to energy or telecommunications networks. The trend toward “AI factories”—large-scale computing facilities designed for national AI development—suggests that geopolitical considerations will increasingly influence technology procurement decisions globally.

For countries caught between American and Chinese technological spheres, these developments create complex strategic choices. Aligning with U.S. technology ecosystems provides access to cutting-edge capabilities but also exposure to American export control policies. Chinese alternatives may offer more predictable access and potentially lower costs, but with questions about performance and international compatibility.

The Innovation Paradox

Perhaps the most profound long-term consequence of this technological bifurcation involves its impact on innovation itself. The global technology sector has long benefited from interconnected research, shared standards, and competitive cooperation that accelerated progress across all participants.

The emergence of parallel AI ecosystems threatens to fragment this collaborative foundation. Different technical standards, incompatible software frameworks, and restricted information sharing could slow the pace of AI advancement globally, even as competition intensifies within each sphere.

Nvidia’s latest earnings report, for all its impressive growth metrics, may represent the high-water mark of American AI companies’ global market dominance. The company’s success has been built on selling the world’s most advanced AI infrastructure to customers regardless of their nationality or political alignment.

As this model becomes increasingly untenable due to security concerns and strategic competition, American technology companies face a fundamental question: Can they maintain technological leadership while serving a smaller, more fragmented global market?

Conclusion: The Real Battle Begins

Behind Nvidia’s $44 billion quarter lies a story that transcends corporate earnings and quarterly guidance. The company’s financial success illuminates the early stages of what may become the defining technological competition of the 21st century: the race to control the infrastructure that powers artificial intelligence.

The immediate numbers tell one story—American companies maintaining commanding technological and market positions. The deeper trends reveal another: the systematic construction of alternative technological ecosystems that could eventually challenge Western dominance across multiple domains.

For Jensen Huang, who built Nvidia from a graphics chip company into the world’s most valuable semiconductor firm, the China restrictions represent both vindication and existential threat. His long-standing warnings about the consequences of technological decoupling are proving prescient, even as they become reality.

The true measure of this quarter’s significance won’t be found in stock prices or revenue growth, but in whether it marked the peak of the globally integrated AI ecosystem—or the beginning of its transformation into something entirely different.

As satellite images reveal construction cranes working around the clock in Shenzhen, and earnings calls discuss lost billions in Chinese revenue, one thing becomes clear: the battle for AI’s future is being fought with balance sheets and fabrication facilities, export licenses and software stacks. Nvidia’s impressive quarter may have been the last chapter in one era’s story, and the first page of another’s.

Premium Note

While mainstream media focused on Nvidia's stock price, you got the real story—complete with satellite intelligence, supply chain analysis, and geopolitical context that won't hit Bloomberg for weeks.

This is exactly why smart money pays for premium analysis: you're seeing around corners while others are still looking at earnings charts.

Share this with your network if you found it valuable. The best strategic insights lose their edge when everyone has them—but right now, you're ahead of the curve.