The Embedding Playbook: China’s Tech Expansion Reveals a New Globalization Model

From transactional sales to ecosystem integration–what the Middle East teaches us about technology partnerships in a multipolar world.

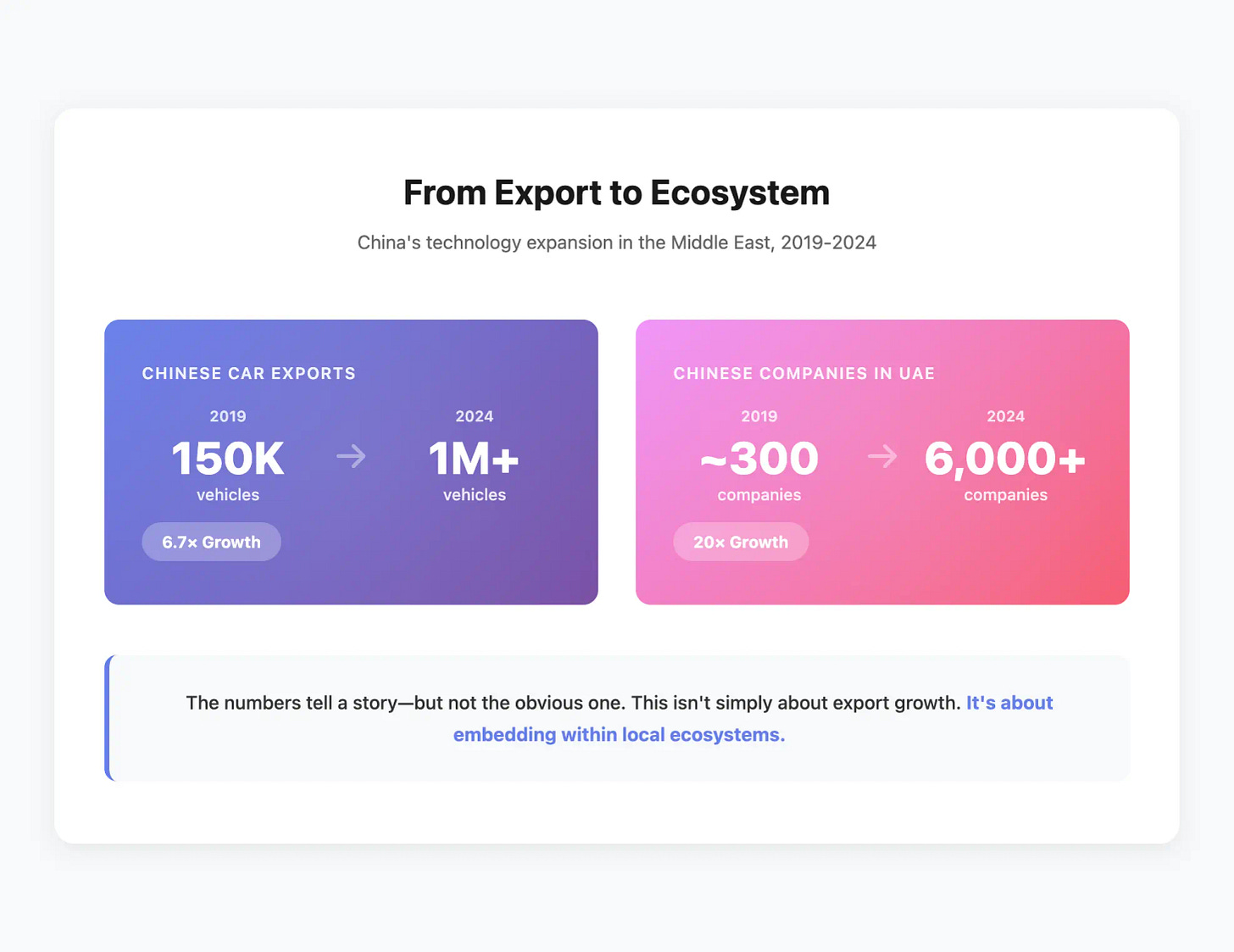

In 2019, China exported 150,000 cars to the Middle East. By 2024: over one million. Chinese companies in the UAE grew from a few hundred to more than 6,000.

The numbers tell a story, but not the obvious one.

Walk through Dubai’s GITEX halls in October 2025. Flying cars, AI office tools, delivery robots–all Chinese. This isn’t simply about export growth or aggressive market expansion. It’s about something more fundamental: a shift from selling products to embedding within local ecosystems.

Why does this matter? Because it reveals a distinct pattern in how Chinese tech globalizes in emerging markets–one that looks nothing like expansion strategies in developed economies. The Middle East, with its sovereign wealth, ambitious digitalization mandates, and regulatory pragmatism, has become the laboratory for a different playbook.

Strategic Alignment Creates the Opening

This isn’t about finding willing customers. It’s about structural convergence between two sets of needs.

Gulf states have made AI and digital infrastructure national priorities. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 positions AI at the center of economic diversification. The UAE has articulated comprehensive strategies linking political leadership, education, infrastructure, and global partnerships. When G42 partnered with OpenAI and Oracle on computing infrastructure, the commitment exceeded $70 billion across the region over five years.

These aren’t experimental pilots. They’re presidential-level commitments backed by sovereign wealth. Middle Eastern states view technology as a development accelerator that can compress timelines, not as gradual modernization.

Meanwhile, Chinese policy frameworks cleared the path. Throughout early 2025, coordinated actions from multiple government agencies systematically removed barriers to tech internationalization. The timing and coordination suggest deliberate strategy rather than scattered initiatives.

Here’s what creates the opening: Both sides actively need this partnership. Middle Eastern nations want rapid technological capability building. Chinese tech firms face domestic market saturation and need growth markets with welcoming regulatory environments. This creates convergent timing–both sides seeking partnership simultaneously, rather than one chasing reluctant prospects.

This alignment shapes everything that follows. It explains why Chinese firms can pursue deep integration instead of arms-length transactions. It clarifies why Middle Eastern governments welcome involvement that might seem intrusive in other contexts. When both sides see strategic value, the relationship dynamics fundamentally change.

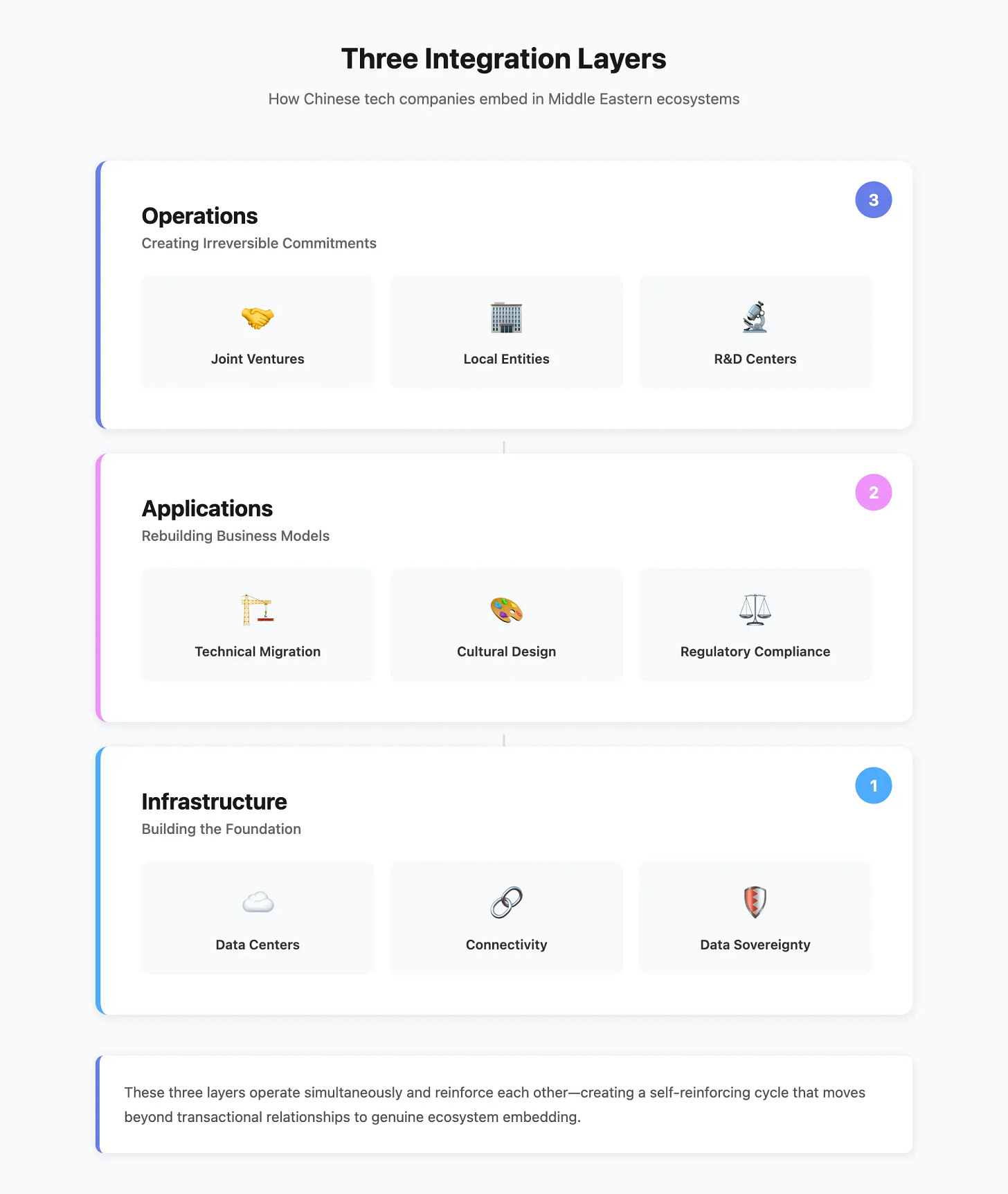

Three Integration Layers Operating Simultaneously

Earlier Chinese tech expansion typically focused on a single competitive layer. What’s emerging now is different–companies operating across three complementary positions at once.

Infrastructure: Building the Foundation

Major Chinese cloud providers are establishing regional data centers and connectivity infrastructure. This serves multiple strategic purposes beyond immediate revenue. It demonstrates long-term commitment through irreversible investment. It creates technical dependencies that make future partnerships more natural. Most critically, it signals acceptance of data sovereignty requirements that have proven non-negotiable.

The strategic logic: Infrastructure players aren’t competing for end-user revenue directly. They’re positioning to enable–and benefit from–all subsequent development in the ecosystem.

Applications: Rebuilding Business Models

This layer reveals the real innovation in globalization strategy.

Consider architectural AI firm Xkool’s approach. They could have pursued straightforward software licensing. Instead, when competing for Dubai Future Foundation selection in 2023 against 600+ global applicants, they committed to comprehensive technical migration. Within months, they had reconstructed their entire platform to conform with UAE construction codes and architectural standards. This wasn’t surface-level localization–it required fundamental re-architecture of core systems.

The investment paid off in a way licensing never could. By August 2025, Xkool’s leadership had formalized an equity partnership with Abu Dhabi Capital Group, establishing a joint holding entity. This made them the first Chinese AI firm to achieve capital-level partnership with emirate-backed wealth. The relationship transcended vendor-client dynamics entirely.

Why this strategy works: Rebuilding core technology for local standards demonstrates serious commitment through irreversible investment. You can’t fake this level of adaptation. It signals you’re building for the long term, which changes how potential partners evaluate you.

WeRide faced different integration challenges when deploying robotaxis in Abu Dhabi. They discovered female passengers had specific concerns about privacy and comfort in autonomous vehicles. Their response went beyond cosmetic changes: electrochromic glass with passenger-controlled transparency, segregated climate control zones, culturally appropriate interface design. These modifications reflected genuine engagement with social norms around gender and public space rather than superficial accommodations.

The results validated the approach: Saudi Arabia’s first autonomous driving license and and substantial revenue growth in the Middle East.

The emerging pattern: Successful companies don’t just adapt products–they rebuild business models from the ground up for local contexts. This level of investment naturally filters out opportunistic players who lack commitment or resources for fundamental re-engineering.

Healthcare robotics firm HuiXin(慧新智能) encountered cultural barriers when hospital demonstrations revealed robot gestures that violated local norms. Rather than tweaking animations, they launched systematic cultural integration: engaging advisors from established cultural research institutions, incorporating religious considerations into core system design, adding recognition capabilities for religious attire, refining sanitation algorithms for religious spaces.

What this demonstrates: Cultural embedding can’t be retrofitted as an afterthought. It requires integration from initial design phases. Companies that understand this principle win contracts. Those attempting superficial adaptation typically fail compliance reviews or lose out in competitive selection.

Operations: Creating Irreversible Commitments

Long-term operational presence represents the deepest form of market commitment. Chengdu-based Bolein(博雷恩科技) has maintained Dubai operations for over a decade with mixed local teams generating steady revenue serving the construction sector. Their work–building electrical systems for new developments–may lack technological novelty, but it demonstrates sustainable presence built on relationships and reliability.

iFlytek illustrates how consumer success can enable enterprise expansion. They sold thousands of intelligent workspace devices in Saudi Arabia based on Arabic language processing capabilities and battery performance that competitors couldn’t match at equivalent price points. But they didn’t stop at consumer sales. They established local entities, recruited regional teams, and deployed enterprise solutions for government agencies and corporations–all with data processing architectures meeting stringent local compliance requirements.

The underlying logic: Long-term operational presence creates substantial switching costs for both parties. Local employees build careers and institutional knowledge. Physical infrastructure can’t be easily relocated. Business relationships compound in value over time. This creates natural barriers to exit that make the relationship more stable.

Multiple Chinese automakers are establishing manufacturing facilities–at least ten announced projects in the past year spanning Egypt, Turkey, Algeria, and the UAE. These represent more than assembly operations. They’re multi-year commitments involving technology transfer and local industrial capacity building.

Why manufacturing matters strategically: It creates employment, transfers technical knowledge, and generates political constituencies who benefit from your continued operation. Host governments evolve from commercial counterparties into stakeholders in your success. This fundamentally transforms the relationship from transactional to strategic.

When Incomplete Commitment Fails

Failure cases illuminate the integration requirements as clearly as successes do.

A Chinese AI security firm collapsed in Saudi Arabia in late 2024 despite winning a substantial smart city contract worth over $20 million. The breakdown stemmed from data sovereignty violations–biometric information flowed back to Chinese data centers rather than remaining fully localized as Saudi data protection statutes required. Company leadership later acknowledged that compliance infrastructure consumed 28% of project budgets, compressing margins from projected 35% to actual 7%. The penalty: permanent loss of all Saudi market access.

Another firm seeking access to Saudi Arabia’s NEOM developmentaccepted terms that ultimately proved unsustainable: joint venture structure giving local partners 49% equity, commitments to train hundreds of Saudi engineers in core algorithmic competencies, contingent buyback obligations if the venture failed to achieve liquidity within specified timeframes. After initial project delivery, the Saudi partner declared autonomous technical capability and excluded the Chinese firm from subsequent procurement opportunities.

What failed cases reveal: Compliance costs function as filters rather than obstacles. They separate firms with genuine long-term commitment from those seeking quick returns. The 25–30% overhead becomes investment in sustainable presence rather than profit drag. In effect, markets use regulatory requirements to screen for serious partners willing to make irreversible commitments.

Industry guidelines now emphasize three non-negotiable requirements: absolute data localization with independent regional infrastructure, dual certification meeting both Chinese and regional standards, and cultural adaptation embedded in system architecture from initial design rather than retrofit.

The deeper pattern: You can’t cut corners on any integration dimension without eventual failure. Data sovereignty shortcuts kill deals or result in contract termination. Technology transfer without retention mechanisms creates competitors who displace you. Cultural insensitivity blocks initial contract awards. Success appears to require systematic progress across all integration dimensions, even when this substantially increases complexity and costs.

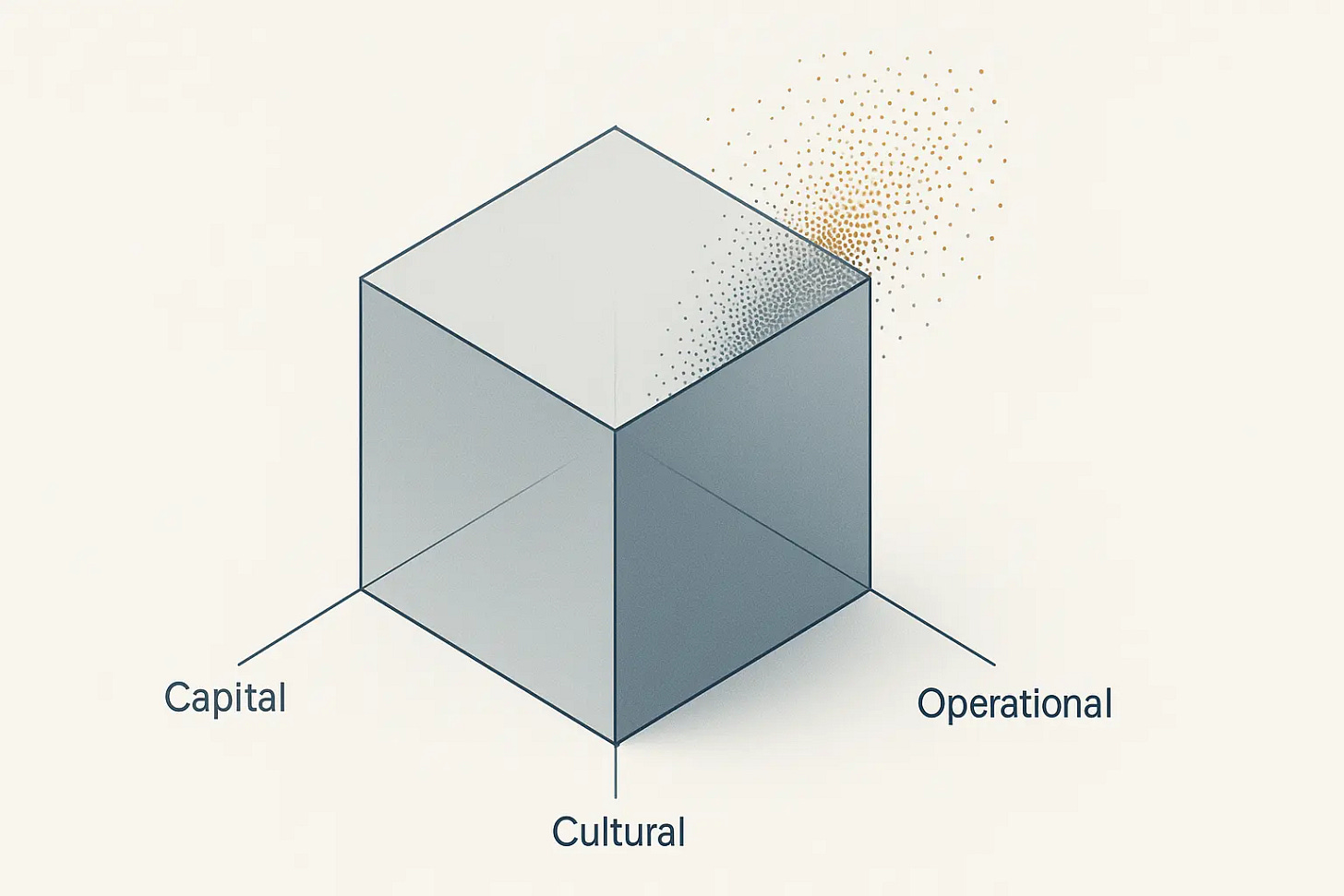

The Three-Dimensional Integration Framework

Synthesizing these patterns reveals how successful embedding advances across three dimensions–often simultaneously but sometimes sequentially.

Capital Integration: Aligning Incentives Structurally

Xiaoку’s joint venture with Abu Dhabi Capital Group exemplifies this deepest integration level. Shared ownership creates aligned incentives that transcend contractual obligations. When local capital takes equity positions in Chinese operations–or Chinese firms acquire stakes in regional entities–both sides gain structural interest in mutual success beyond what contracts can achieve.

This pattern recurs across sectors: sovereign wealth investments in Chinese EV manufacturers, G42 partnerships with Chinese AI infrastructure providers extending beyond procurement into co-development arrangements.

Why this represents the deepest integration: Exit becomes nearly impossible without substantial losses for both parties. This creates powerful commitment mechanisms that contracts alone can’t replicate. When both sides lose significantly if the relationship fails, they invest much more heavily in making it work.

Operational Integration: Building Exit Barriers

iFlytek’s regional offices and teams, automotive manufacturers’ planned production facilities, Bolein’s decade-long operational history–these demonstrate operational integration that creates substantial switching costs. This means local hiring under local jurisdiction, establishing legal entities subject to host country law, and making fixed investments that can’t be withdrawn without substantial losses.

Automotive manufacturers establishing production across Egypt, Turkey, Algeria, and the UAE are making multi-year commitments involving technology transfer and local capacity development–investments that can’t be easily reversed or relocated.

The strategic logic: Operational integration creates bilateral switching costs. You can’t easily relocate manufacturing infrastructure. Local employees have career investments and institutional knowledge that would be lost. Physical presence generates political constituencies–employees, suppliers, local partners–who benefit from your continued operation and may resist your exit or displacement.

Cultural Integration: Earning Social License to Operate

WeRide’s privacy-adaptive vehicle design and HuiXin’s systematic cultural consultation represent the subtlest but potentially most powerful integration dimension. This isn’t just about understanding what users want–it’s about comprehending why they want it, the cultural contexts and value systems that shape preferences and expectations.

Cultural integration can’t be simulated or artificially accelerated. It requires sustained immersion, genuine local partnerships, and willingness to fundamentally reconsider product assumptions that may work elsewhere but fail in new contexts.

Why this dimension may matter most: You can achieve capital and operational integration but still fail without cultural acceptance. Technology that violates social norms gets blocked regardless of economic logic or contractual agreements. Cultural fit often determines whether local stakeholders actively support or passively resist your presence–a difference that proves decisive in competitive situations.

How these dimensions interact: Capital integration without operational presence proves fragile and vulnerable to policy shifts or political changes. Operational presence without cultural sensitivity breeds local resentment that eventually manifests in regulatory obstacles or contract losses. Cultural adaptation without capital or operational commitment may win goodwill but fails to establish defensible market position.

The most successful integration trajectories appear to advance progressively: establishing operational presence first to demonstrate commitment, developing cultural sensitivity through genuine adaptation over time, and ultimately achieving capital integration through joint ventures or equity partnerships as trust builds. Each dimension reinforces the others, creating compounding advantages.

Three Questions That Shape What Comes Next

Rather than enumerating metrics to track, three fundamental questions better frame how this pattern might evolve and what it means beyond immediate context.

Can This Model Transfer to Other Markets?

The Middle East presents unusual enabling conditions: massive sovereign wealth seeking deployment opportunities, ambitious state-led development programs, and regulatory systems offering flexibility to strategically valuable partners. The critical question: Which embedding elements depend specifically on these characteristics, and which might transfer to other emerging markets?

Southeast Asia lacks comparable sovereign capital concentration but shares rapid digitalization imperatives and growth trajectories. Latin America presents different regulatory environments but similar infrastructure development needs. Sub-Saharan Africa offers distinct institutional challenges around state capacity and capital availability.

What matters for transferability: Understanding which integration dimensions prove universal versus context-dependent will determine whether we’re observing a Middle East-specific phenomenon or a generalizable model for emerging market expansion.

A testable hypothesis: Capital integration may require sovereign wealth concentration or large-scale capital availability, but operational and cultural integration could work in any growth market with welcoming policy environments. Observing Chinese tech expansion patterns in other regions for similar integration approaches would test this hypothesis.

When Does Partnership Become Unwelcome Dependency?

Middle Eastern nations explicitly aren’t seeking permanent technological dependency. They want accelerated capability building. National strategies across the region articulate goals of developing indigenous tech sectors through knowledge transfer and local talent development.

This raises a critical question: At what point does “embedding” transition from welcome partnership to unwelcome entrenchment that host governments actively resist?

The transition point likely varies by sector, national strategy, and perceived success in achieving technology transfer goals. Some Gulf states may prefer maintaining long-term partnerships with established providers even as local capabilities grow. Others appear to view current collaborations as transitional phases toward eventual full autonomy.

The critical variable appears to be: Whether Chinese firms actively help partners achieve stated technological sovereignty goals, or whether they attempt to maintain permanent dependency relationships. Successful firms likely will be those enabling local capability development even when this creates future competitors. Failed firms will be those trying to preserve dependency, which host governments will eventually recognize and resist.

Does This Pattern Redefine Globalization Itself?

For decades, technology globalization followed a standardization model: develop products for home markets, then extend globally with minimal adaptation to capture economies of scale. This approach worked when technological leadership concentrated in a few developed markets and emerging economies primarily functioned as technology importers accepting products on suppliers’ terms.

The embedding model suggests something qualitatively different: deep integration within local ecosystems, fundamental adaptation to specific contexts, and genuine partnership rather than unilateral expansion. This approach acknowledges that emerging markets aren’t simply technology recipients–they’re active participants who increasingly shape how innovation develops and deploys in their contexts.

If this model proves successful and replicable, the implications extend well beyond Chinese companies and Middle Eastern markets. European firms expanding in Asia, American companies entering African markets, or any technology provider operating across diverse institutional contexts may need to reconsider fundamental assumptions about how globalization works.

What appears to be changing: The balance of power in technology adoption relationships. When emerging markets had limited alternatives, they often accepted standardized products on suppliers’ terms. As options proliferate and local capabilities grow, they can demand deeper adaptation and partnership. Chinese firms offering more comprehensive integration gain advantages over competitors offering standardized global products.

This isn’t necessarily about Chinese companies being inherently smarter or more capable. It may reflect structural conditions–intense domestic competition forcing international diversification, state support enabling patient capital deployment, operational experience across diverse domestic regional contexts–that create specific capabilities for this embedding approach. Other companies from other origins might develop similar capabilities under similar conditions.

What This Signals

Those million vehicles and 6,000 companies represent more than impressive market penetration statistics. They demonstrate an emerging model where both sides function as active architects of the relationship rather than one side simply supplying and the other consuming.

The Middle East’s distinctive combination of available capital, developmental ambition, and policy openness made it an ideal laboratory for testing this approach. Whether the experiment ultimately succeeds–and whether its lessons prove transferable to other contexts–will likely shape technology globalization patterns for years to come.

For practitioners: In emerging markets with strong state capacity and clear development priorities, success increasingly appears to require moving beyond transactional relationships toward structural integration. This means embedding capabilities, capital, and cultural understanding within local ecosystems–not just selling products across borders.

For observers: The Chinese tech industry’s Middle Eastern experience offers more than a regional case study. It provides insights into how innovation diffuses across different institutional contexts and how globalization itself may be evolving in response to shifting global power distributions.

The broader pattern that may be emerging: Technology globalization is fragmenting into multiple models rather than following a single dominant pattern. Success increasingly requires matching strategy to specific contexts. The embedding approach appears to work in emerging markets with welcoming governments and strong growth imperatives. It likely wouldn’t work in mature markets with entrenched competitors and restrictive regulatory environments.

Understanding when to apply which model–standardization versus embedding, transaction versus integration–may become a core competency for technology companies seeking global reach in an increasingly multipolar world where one-size-fits-all approaches prove less effective.

Continue the Analysis

This framework launches a multi-part examination of Chinese tech globalization. I’ll explore sector variations, geographic limits, and competitive responses through paid subscriber deep-dives over coming months.

Paid subscribers receive:

2–3 long-form strategic analyses weekly across China’s tech sector

FlashPoint: Rapid analysis of breaking developments

Complete access to 50+ archived insights

Independent analysis. No PR influence.

It's interesting how you framed this, a reall deep dive into the embedding part. Do you think data sovereignty becomes an even bigger challenge with this model?