China Turns IPOs Into Industrial Policy: The Commercial Space Case

Orbital insertion is now a listing requirement. China is turning IPOs into space infrastructure funding.

The commercial space sector in China is experiencing an unusual surge in IPO activity. Companies losing billions of yuan annually are preparing to list at multi-billion yuan valuations. Investors who spent years in obscurity are now fielding nonstop calls from local government funds and securities analysts. Capital is flooding into the sector faster than viable projects can emerge.

Something fundamental has shifted. But this is not the familiar story of venture-backed startups reaching commercial maturity and going public. The pattern here points to something different.

Why Unprofitable Rocket Companies Trade at Billion-Yuan Valuations

First paradox: Money chases unprofitable companies at billion-yuan valuations.

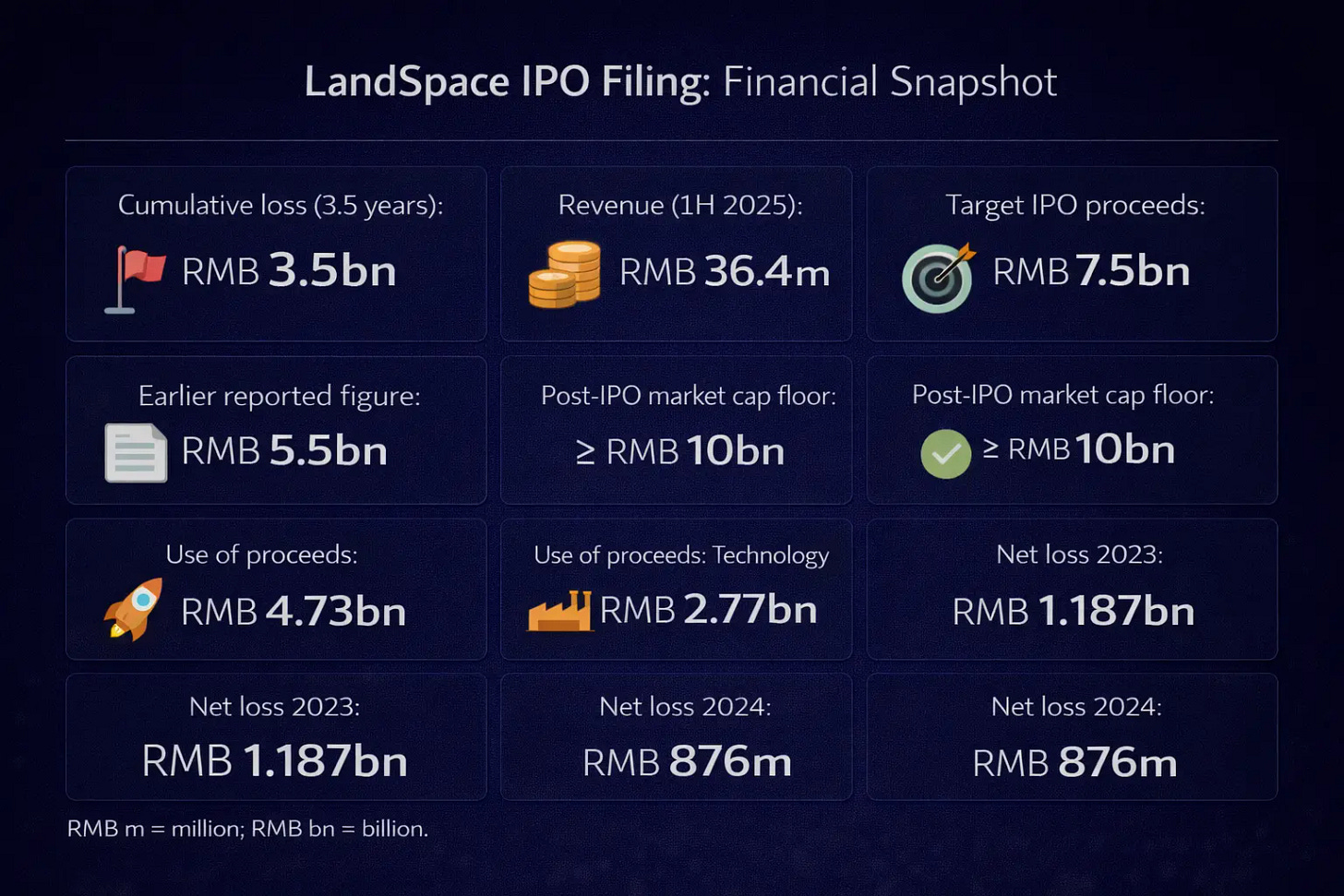

LandSpace, one of the leading private rocket companies, lost nearly RMB 3.5 billion over three and a half years. In the first half of 2025, the company generated just RMB 36.4 million in revenue. Yet the filing targets RMB 7.5 billion in proceeds, up from earlier RMB 5.5 billion figures reported before the prospectus was published. The prospectus implies a post-IPO market cap of no less than RMB 10 billion.

This is not an isolated case. At least 10 commercial space companies have entered the IPO pipeline, including five launch-vehicle specialists. Many remain loss-making, with annual losses reaching billions of yuan rather than hundreds of millions. LandSpace posted net losses ranging from RMB 876 million to RMB 1.187 billion in 2023–24. Yet their valuations keep climbing.

Second paradox: Technical milestones replace financial metrics as the gating factor.

On December 26, 2025, the Shanghai Stock Exchange published new guidelines for commercial rocket companies seeking to list under the fifth set of listing criteria on the STAR Market. The key requirement: companies must achieve at least one payload successfully inserted into orbit by a medium-to-large launch vehicle using reusable technology before filing.

This is highly unusual. Capital markets typically screen companies using revenue thresholds, profit margins, or cash flow metrics. Here, the exchange is explicitly using technical achievement as the prerequisite. Financial performance becomes secondary.

One investor with seven years of experience in commercial space put it bluntly in an interview: “The state opened capital markets to provide blood transfusions for companies building infrastructure.”

Third paradox: More capital than investable projects.

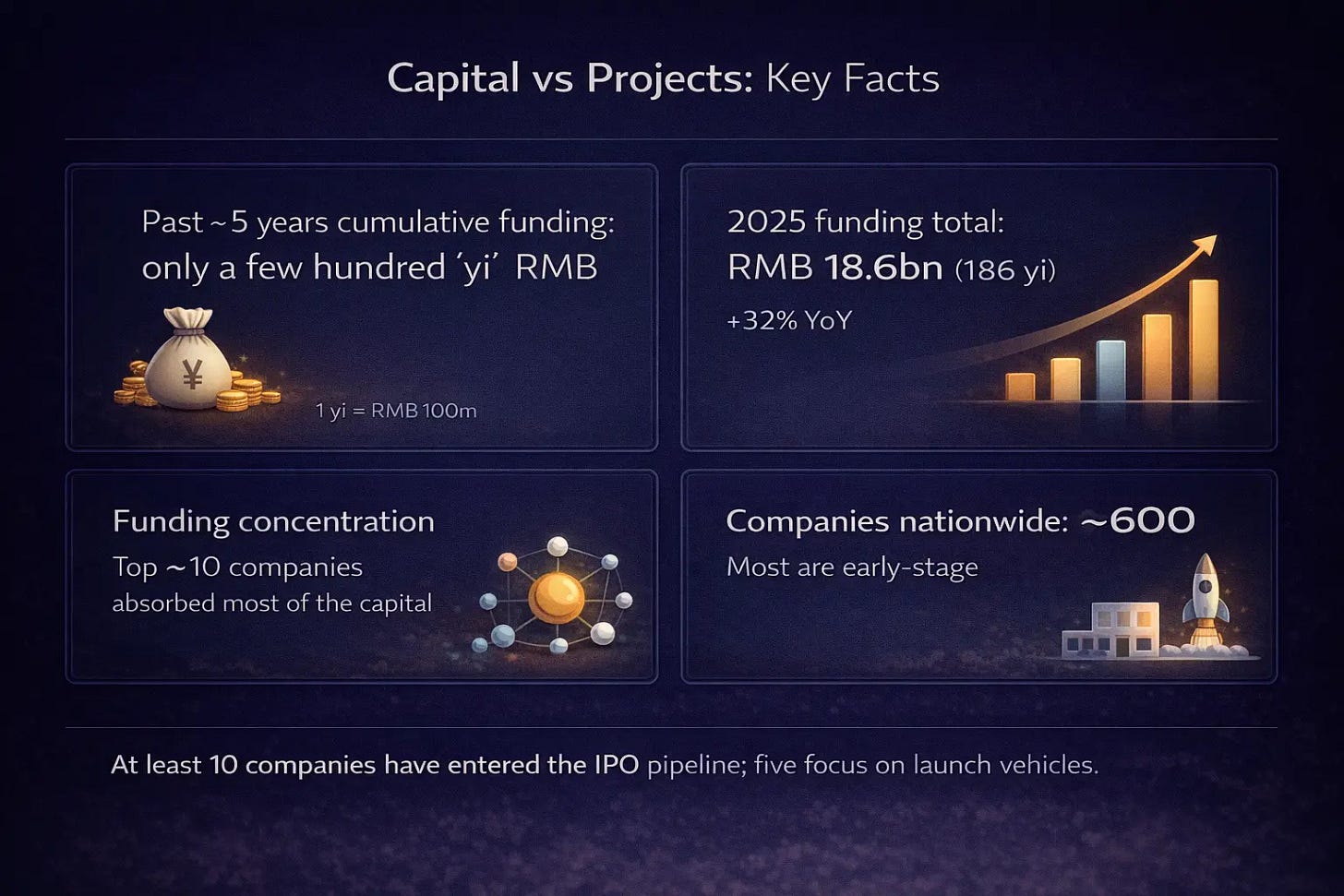

The same investor described a striking reversal. For years, commercial space was a neglected corner of the venture ecosystem. Total fundraising across the sector over five years amounted to just tens of billions of yuan, a fraction of what artificial intelligence companies were raising in single rounds.

Now capital is arriving faster than companies can absorb it. Multiple local government funds are setting up dedicated vehicles for commercial space. But the total number of viable companies in China remains small, around 600, with most still in early development stages. Investors openly acknowledge that good projects are scarce.

These three paradoxes cannot be explained by standard market dynamics. They point instead to a coordinated effort.

The Three-Part Mechanism: Risk Distribution, Technical Discipline, and Exit Paths

Strip away the language of “commercial space” and what emerges is clearer. China is using public equity markets to fund the construction of space infrastructure. This is not about helping mature companies access growth capital. This is about channeling public market money into a sector that private capital alone would not build at the required scale and speed.

The mechanism has three components working together.

Risk distribution through public markets. By enabling IPOs for pre-revenue companies, China spreads the financial burden of infrastructure construction across millions of retail and institutional investors. This is more politically sustainable than concentrating the cost in state budgets. When a rocket company loses money, the loss is shared across a diffuse investor base rather than appearing as a line item in government accounts.

Technical verification as market discipline. The requirement for successful orbital launch before IPO filing serves a specific function. It filters out purely speculative ventures while allowing technically credible but commercially immature companies to access capital. This creates a gate that demands engineering progress without requiring profitability.

Consider the timeline and what counts as success. The Shanghai Stock Exchange published its rocket company guidelines on December 26. Just five days later, LandSpace’s IPO application was accepted. The company’s Zhuque-3 rocket had achieved China’s first successful orbital insertion using a reusable design on December 3, though the recovery test failed. The timing is hard to miss, and the technical bar was set at orbital insertion rather than full reusability.

Ecosystem sustainability through exit paths. Early investors in commercial space endured years of skepticism. One venture partner recounted being labeled “unreliable” when he decided to focus on the sector in 2018. The question then was not whether the technology would work but whether anyone would use it.

These early backers provided patient capital when the sector had no clear commercial model. The IPO pathway offers them a credible exit, which in turn makes it possible to attract the next wave of investment. Without this, the ecosystem would stall.

System Resilience Over Single-Company Efficiency

The logic becomes clearer when comparing China’s model with the dominant alternative. In the United States, SpaceX has effectively become the national launch provider. It handles cargo and crew transport to the International Space Station, deploys national security satellites, and operates the world’s largest satellite constellation. The company’s success is undeniable. But it also creates concentration risk.

American space policy now hinges on a single private entity. When SpaceX encounters technical issues or capacity constraints, the entire system feels the impact. There is no redundancy. The company’s founder holds enormous leverage over national priorities.

China is pursuing a different architecture. Rather than betting on one dominant player, the state is enabling multiple companies to develop parallel capabilities. This has costs. It means accepting some duplication and inefficiency. But it also creates system resilience. No single company failure can derail the broader program.

The current IPO wave fits directly into this strategy. By providing public market access to technically credible but commercially immature companies, China ensures that multiple teams can continue developing rocket technology even as they burn through capital. The state sets technical thresholds to maintain standards. The market provides the funding. Companies compete on execution.

This is industrial policy operating through financial markets rather than direct subsidies. It allows the state to maintain strategic direction while distributing financial risk.

From Infrastructure Build-Out to Revenue Generation

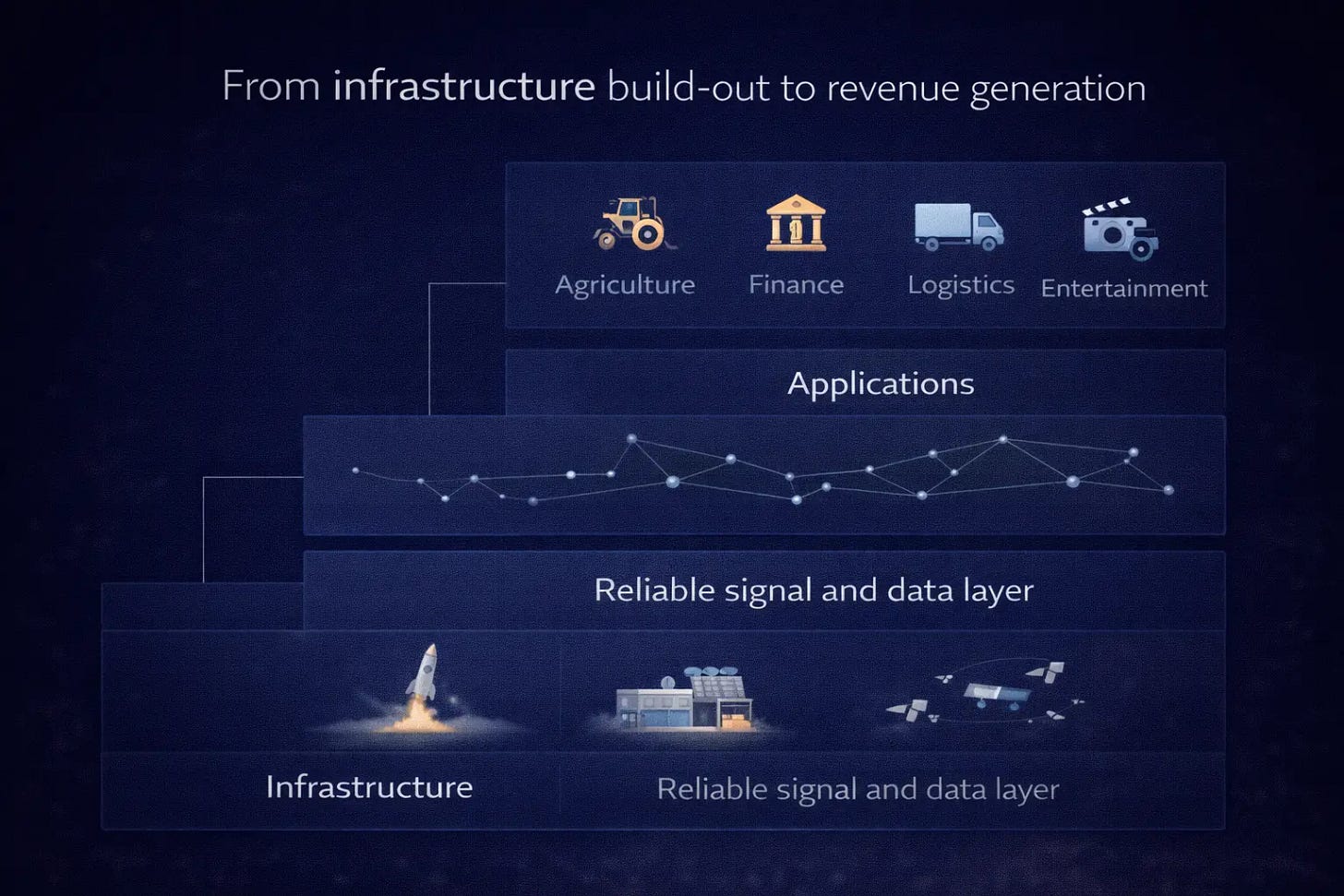

The current phase is what one investor described as “adding space” rather than “space plus.” Companies are focused on building core capabilities: rocket launches, satellite manufacturing, constellation deployment. This is the infrastructure layer.

The model works well for this phase. Public markets can fund expensive, long-cycle engineering projects if investors believe the infrastructure will eventually generate returns. The question is what happens next.

For this approach to succeed over the long term, the infrastructure must enable applications that generate sustainable revenue. The “space plus” phase must materialize. Think space-enabled precision agriculture, logistics tracking, financial data services, or other use cases that justify the massive capital expenditure.

If those applications emerge and scale, the companies that built the infrastructure can transition from capital-intensive construction to asset-light service provision. Cash flow improves. Valuations stabilize. The IPO wave looks prescient.

But if demand fails to materialize at the expected scale, China will have created expensive infrastructure with limited utilization. The risk is not that individual companies fail. The risk is that the entire model proves to have been premature.

The capital allocation data suggests awareness of this challenge. Of LandSpace’s RMB 7.5 billion fundraising plan, RMB 4.73 billion is earmarked for technology development and only RMB 2.77 billion for capacity expansion. The priority remains technical advancement rather than scaling production. This makes sense if the company believes it needs further breakthroughs before commercialization becomes viable.

China’s commercial space sector is entering a critical transition. The IPO wave is not a sign that companies have reached maturity. It is a mechanism for funding the next stage of development. Whether that mechanism proves effective depends on factors that remain uncertain: the true cost structure of reusable rockets, the pace of satellite constellation deployment, and most importantly, whether space-enabled services find product-market fit at commercial scale.

What is already clear is that China has found a novel way to use capital markets as industrial policy tools. Success will not be measured by individual company profitability in the near term. It will be measured by whether the infrastructure gets built and whether it eventually enables the economic activity that justifies its cost. That outcome is still years away from being determined.

An IPO as a way to fund development is pretty similar to what a lot of Western “space companies” (and other emerging-tech plays) have done. In that sense, China looks less like it’s doing something novel and more like it’s catching up to an established Western-market pattern.

Enjoy reading your articles!

Don't know if it will look right, but over on X, posted this with Epoch Times article from yesterday providing insight on Zhang Youxia's removal and probably cracking in their military.

In game of multi level chess, it is important to remember parallel pathways.