Platform Capitalism’s Civil War: A Tale of Two Asias

As the world sours on the Silicon Valley model, two challengers in China and India are pioneering starkly different futures for the gig economy. One is a reformation; the other, a revolution.

For the better part of a decade, the narrative surrounding the platform economy has been one of predictable conflict. In courtrooms from London to California and in the halls of parliament in Brussels, regulators have grappled with the disruptive force of Silicon Valley’s gig economy titans. The battle lines were clearly drawn: disruptive, capital-flush platforms on one side; unions, taxi guilds, and governments on the other. The central question seemed to be how to tame, tax, and regulate a model that often grew faster than the laws designed to contain it.

Yet, while the West has been mired in a slow, attritional war of legal challenges and legislative tweaks, the true future of the platform economy is being forged elsewhere. The most radical and potentially consequential challenges to the Uber-Didi paradigm are not emerging from Western regulators, but from the bustling streets of Asia’s two largest economies.

In China and India, two deceptively similar ride-hailing applications are mounting a quiet insurrection. Both have adopted a subscription-based model for drivers, slashing the punitive commissions that have long been the industry standard. But to see them as mere low-cost copycats is to miss the profound divergence in their philosophies. China’s Xiaola Chuxing (小拉出行, or “Lala Ride”), a service born from logistics giant Lalamove, represents a pragmatic reformation—a capitalist fix for capitalism’s own excesses. India’s Namma Yatri, meanwhile, is waging an ideological revolution, attempting to replace the very foundations of platform capitalism with a community-owned, open-source alternative.

The competition between these two models is more than a regional business story. It is a live-fire experiment testing two fundamentally different futures for the digital economy. For global investors, policymakers, and executives, the question is no longer just how to regulate Silicon Valley’s model, but which of these emerging Asian paradigms will define the next decade of digital commerce.

The First Path: A Pragmatic Reformation in China

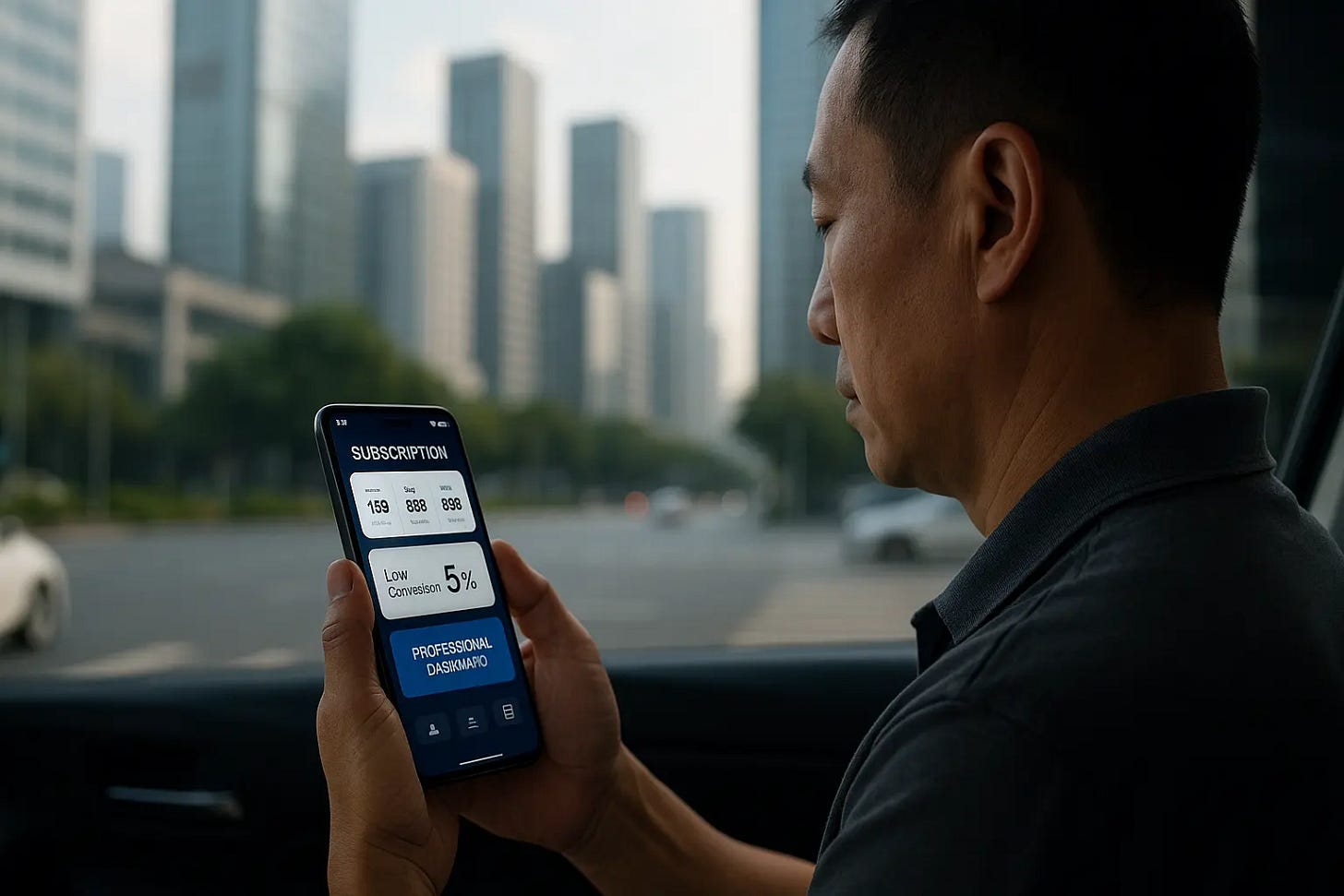

On the surface, Xiaola Chuxing’s proposition is simple and compelling. While dominant players like Didi Chuxing typically extract a commission of 20–30% from each fare, Xiaola Chuxing offers its drivers a different deal. Pay a modest monthly subscription fee, and you can operate on the platform with a commission rate as low as 5%, sometimes even less. For drivers, whose margins are perpetually squeezed, the appeal is immediate and tangible: a predictable cost structure and a significantly larger share of their earnings.

This is not charity; it is shrewd business strategy. To understand Xiaola Chuxing’s model, one must understand the hyper-competitive, almost Darwinian, ecosystem of Chinese technology. In a market defined by brutal price wars and monolithic incumbents, survival depends on radical efficiency and novel approaches to unit economics. Xiaola Chuxing’s innovation is not technological, but structural. It has performed a kind of cost-structure arbitrage.

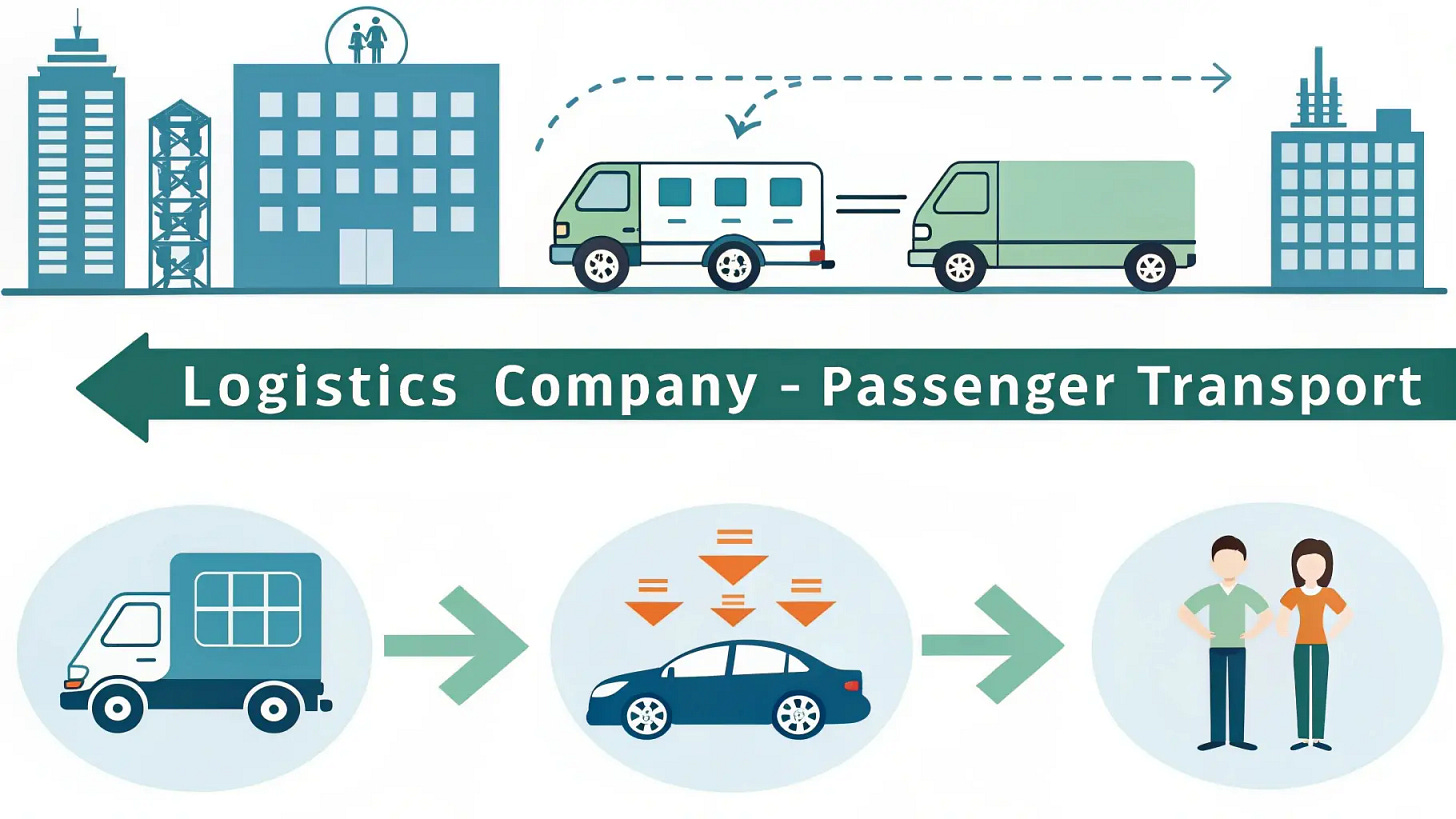

The key to its model lies in two areas. First is its genesis. Xiaola Chuxing is not a venture-backed startup burning cash to acquire users, but a strategic extension of an existing, profitable business. As the passenger-ride offshoot of the logistics giant Lalamove (known as Huolala in China), it leverages an established network of drivers, brand recognition, and operational infrastructure. This vertical integration dramatically lowers the two most significant costs in ride-hailing: driver and customer acquisition. It doesn’t need to spend billions on marketing to build a brand from scratch; it can cross-sell to an existing user base.

Second, the model represents a fundamental shift in the platform-provider relationship, what could be termed the “SaaS-ification” of the gig economy. Instead of treating drivers as transactional counterparties from whom value must be extracted on every ride, the subscription model reframes them as B2B clients. The platform becomes a Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) provider, selling a tool (access to passengers) for a recurring fee. This aligns incentives in a way the commission model never could. The platform’s success is no longer tied to maximizing its take from each fare—a zero-sum game with the driver—but to retaining its paying subscriber base by providing a steady stream of valuable leads. This transforms a volatile, transaction-based revenue stream into a more predictable, recurring one, a holy grail for any modern business.

This is a reformation, not a revolution, because it never questions the fundamental tenets of platform capitalism. It still relies on network effects, seeks scale, and is ultimately driven by a profit motive. It doesn’t seek to dismantle the centralized platform; it seeks to run it more efficiently. It tacitly accepts that a central authority is necessary to manage matching, payments, and trust, but argues that this authority can be sustained with a much lower economic rent. It is a lean, cost-conscious, and arguably more sustainable iteration of the model it seeks to displace. It is a solution born of intense market pressure, a testament to the idea that sometimes the most effective critique of capitalism comes from a smarter, more disciplined form of capitalism itself.

The Second Path: An Ideological Revolution in India

Travel southwest to India, and you find Namma Yatri, a platform that appears, at first glance, to be a kindred spirit. Launched in Bengaluru, it too offers drivers a way out of the high-commission trap, initially operating on a zero-commission basis before introducing a nominal daily subscription fee. Uber and its local rival Ola have been so rattled by its growth that they have been forced to launch their own subscription plans in response.

But to equate Namma Yatri with Xiaola Chuxing is to mistake the symptom for the cause. Its low fees are not the product of a superior business model, but the expression of a radical political and social ideology. If Xiaola Chuxing is a reformation, Namma Yatri is a full-blown revolution aimed at the governance structure of the platform itself.

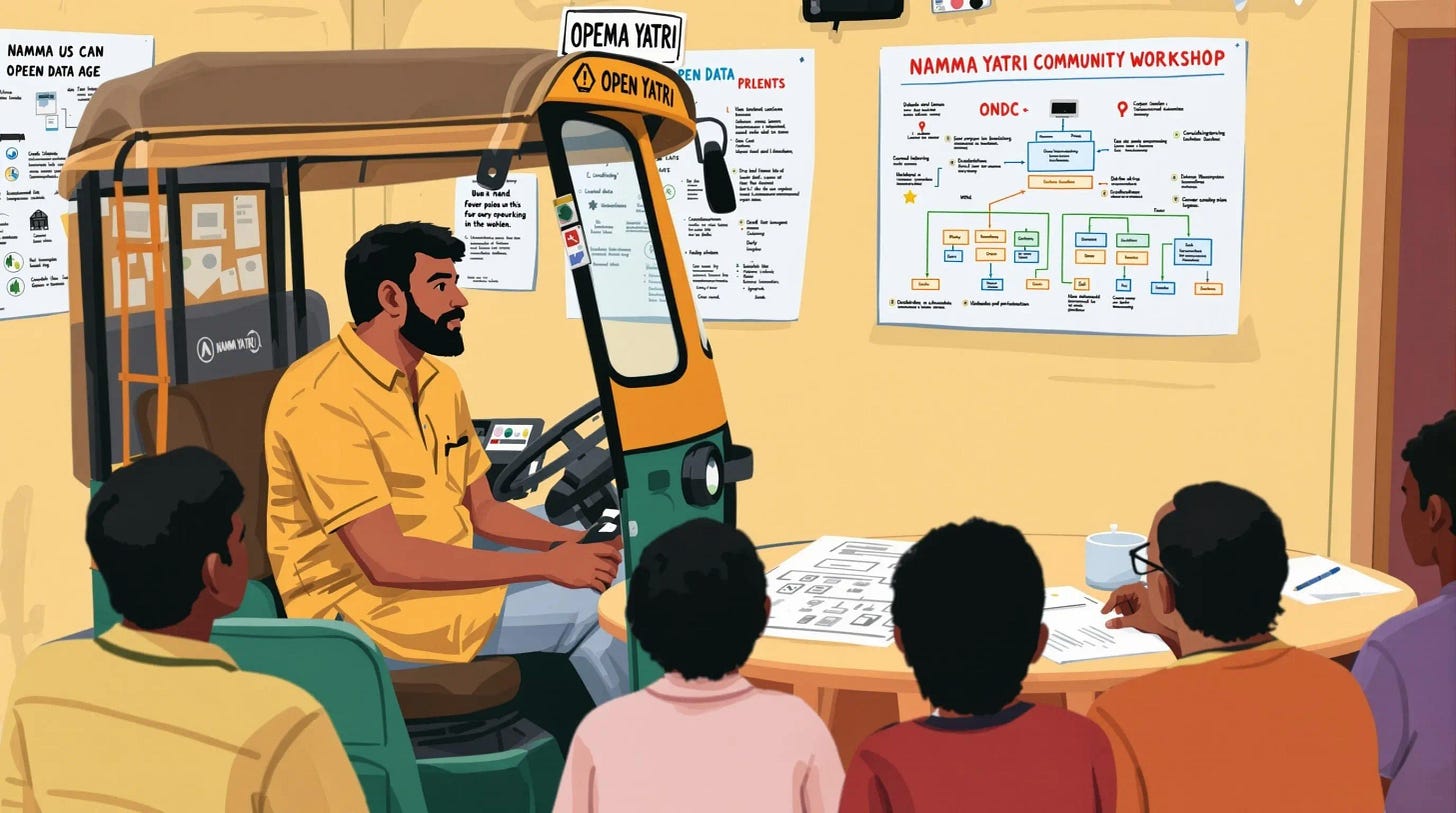

Its origins tell the story. Namma Yatri was not incubated within a corporate giant. It was co-created by a fintech firm (Juspay), a non-profit foundation promoting open protocols (FIDE), and, crucially, the Bengaluru Auto Rickshaw Drivers’ Union. From day one, its purpose was not simply to lower costs, but to decentralize power. It was designed as an antidote to the opaque, exploitative practices of the incumbent platforms.

This philosophy is embedded in its architecture. Namma Yatri is built on an open protocol and operates with a startling degree of transparency. It is the only major ride-hailing app in India that makes its key operational metrics—such as driver earnings, trips completed, and search trends—publicly accessible on its website. This is not a marketing gimmick; it is a foundational principle. By making data open, it dismantles the information asymmetry that gives centralized platforms their immense power over drivers.

Furthermore, Namma Yatri is deeply integrated with a grander national project: the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC). ONDC is a government-backed initiative to unbundle e-commerce, creating a common, open-source digital infrastructure that prevents any single platform, whether Amazon or Uber, from becoming a monopolistic gatekeeper. In this context, Namma Yatri is less a standalone company and more an application layer built atop a piece of digital public infrastructure. It is a proof-of-concept for a new kind of platform economy, one based on interoperable protocols rather than proprietary, walled-garden ecosystems.

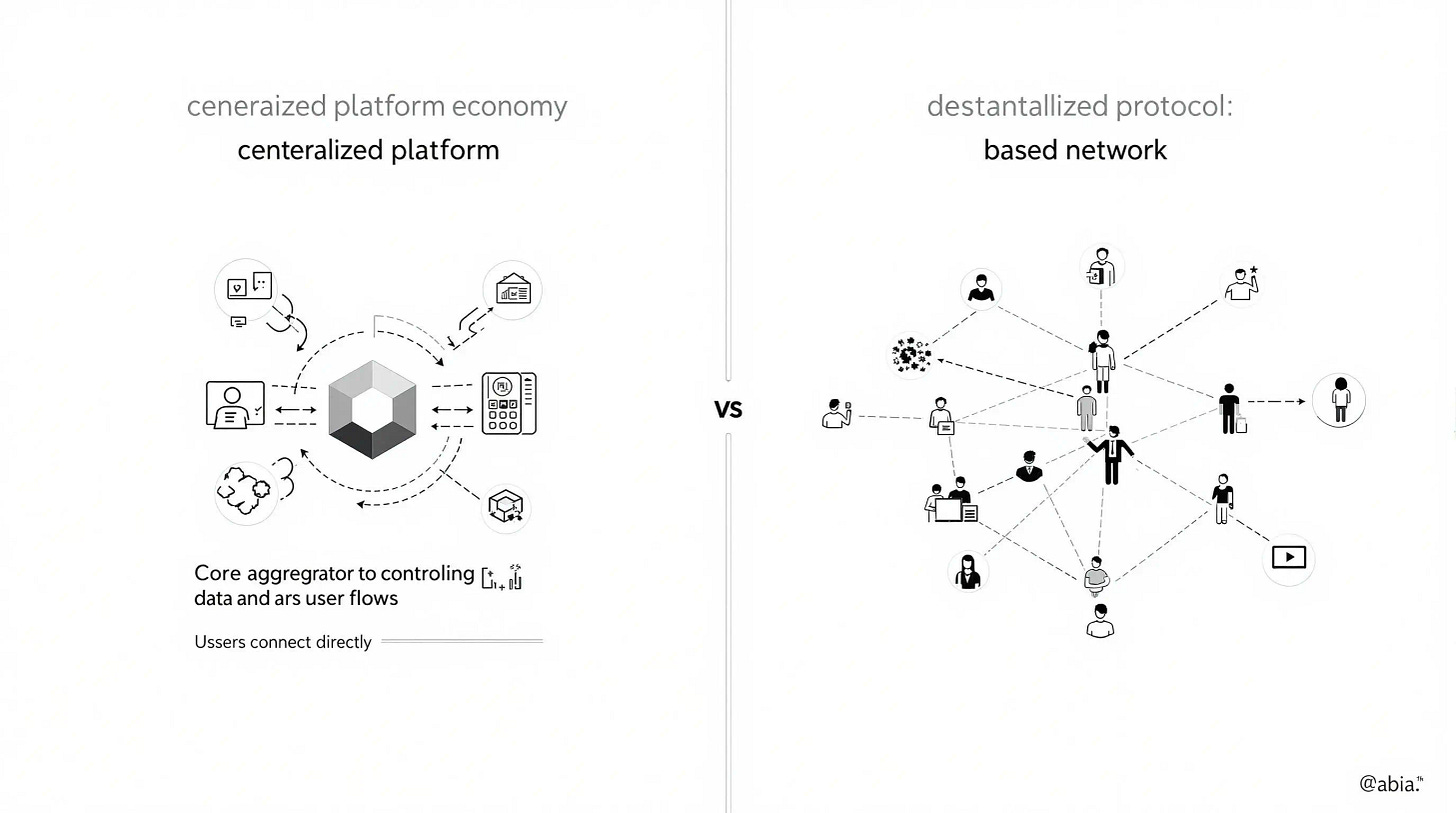

This is the core of the revolution: the shift from a platform economy to a protocol economy. In the old model, Uber owns the platform, the data, the algorithm, and the customer relationship. It is a central aggregator of value. In the Namma Yatri model, the protocol is open. The platform is merely a thin layer that facilitates a connection, with passengers paying drivers directly. Value is retained at the edges of the network—with the drivers and the community—not hoarded at the center. It seeks to answer a far more profound question than its Chinese counterpart: “Do we even need a powerful, centralized platform to begin with?” Its innovation is not in business, but in governance.

The Geopolitical Subtext: Why Here, Why Now?

The emergence of these two distinct models is no accident. Each is a unique product of its national soil, shaped by different political economies and technological trajectories.

China’s environment fosters the reformation model. It is a state-guided market economy characterized by intense domestic competition among a handful of tech behemoths. In this arena, the path to success is paved with operational excellence, relentless optimization, and the ability to achieve massive scale. Innovation is often driven by finding efficiencies within an established paradigm. Xiaola Chuxing’s focus on cost-structure arbitrage and its symbiotic relationship with a parent company is a classic strategy born from this environment. It is a market-driven solution in a market where efficiency is king.

India, by contrast, provides fertile ground for a revolution. Its democratic, and often chaotic, political landscape coexists with a vibrant civil society and a strong tradition of unionization and collective action. The collaboration between a tech firm and a drivers’ union to build Namma Yatri is a uniquely Indian story. Simultaneously, the Indian state has embarked on an ambitious strategic mission to build its “India Stack”—a suite of public digital goods like the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and ONDC. This is a conscious effort to establish digital sovereignty and create an alternative to both the American model of venture-capital-led platform monopolies and the Chinese model of state-supervised tech giants. Namma Yatri is the perfect embodiment of this third way: a grassroots, community-driven initiative built on top of a state-sponsored public protocol.

The Investor’s Dilemma and The Outlook

For global capital, these two paths present a fascinating and complex choice. Which model is the more sound investment? Which holds the key to the future? Each faces its own formidable set of challenges.

Xiaola Chuxing’s challenge is one of scale and incumbency. While its model is capital-efficient, it still must contend with the immense network effects of a giant like Didi. Can a low-cost structure alone be a sustainable moat? Or will the incumbent, with its deeper pockets and larger pool of drivers and riders, simply tolerate the challenger in certain niches or launch its own subscription-based sub-brand to neutralize the threat? The bet on the Chinese model is a bet on operational excellence and the belief that a more efficient, centralized platform will ultimately win.

Namma Yatri’s challenge is the eternal conflict between ideals and user experience. Its community-first, open-source ethos is its greatest strength, but it could also be its Achilles’ heel. Can a decentralized, community-governed network deliver the seamless, reliable, and instantly available service that users have come to expect from the algorithmically optimized, centrally managed Uber? More critically, as Namma Yatri has recently taken on venture capital from firms like Google and Blume Ventures, it faces an existential question: can it serve two masters? How does a platform built on the principle of returning value to the community reconcile that with the growth and exit expectations of its venture backers? The bet on the Indian model is a bet that a fairer governance structure can build a powerful enough community to overcome potential deficiencies in capital and slickness.

Conclusion: The Battle for the Soul of the Digital Economy

The quiet competition unfolding on the streets of Guangzhou and Bengaluru is far more significant than a skirmish over ride-hailing market share. It is a battle for the soul of the digital economy. It pits a lean, efficient, but ultimately conventional form of platform capitalism against a radical, idealistic, and unproven model of digital cooperativism.

The era of the Silicon Valley playbook—of blitzscaling, regulatory arbitrage, and winner-take-all dynamics—is visibly waning. Its successor is yet to be crowned. Will it be a reformed, more sustainable version of the centralized platform, as pioneered in China? Or will it be a revolutionary, decentralized protocol that hands power back to its users, as envisioned in India?

The answer is not yet written. But for any global observer trying to understand where the world’s digital future is headed, the gaze must turn eastward. The West may be busy litigating the past, but in Asia, two starkly different futures are already under construction.

About Hello China Tech

I’m Poe Zhao, and I bridge the gap between China’s rapidly evolving tech ecosystem and the global community. Through Hello China Tech, I provide twice-weekly analysis that goes beyond headlines to examine the strategic implications of China’s technological advancement.

Found this useful?

→ Share this newsletter with colleagues who need to understand China’s tech impact

→ Subscribe for free to receive every analysis: