China Shipped Millions of AI Toys While the West Was Still Debating

How a $3.5 billion industry emerged from supply chains, cheap LLMs, and a generation’s loneliness–and what it means for the future of childhood.

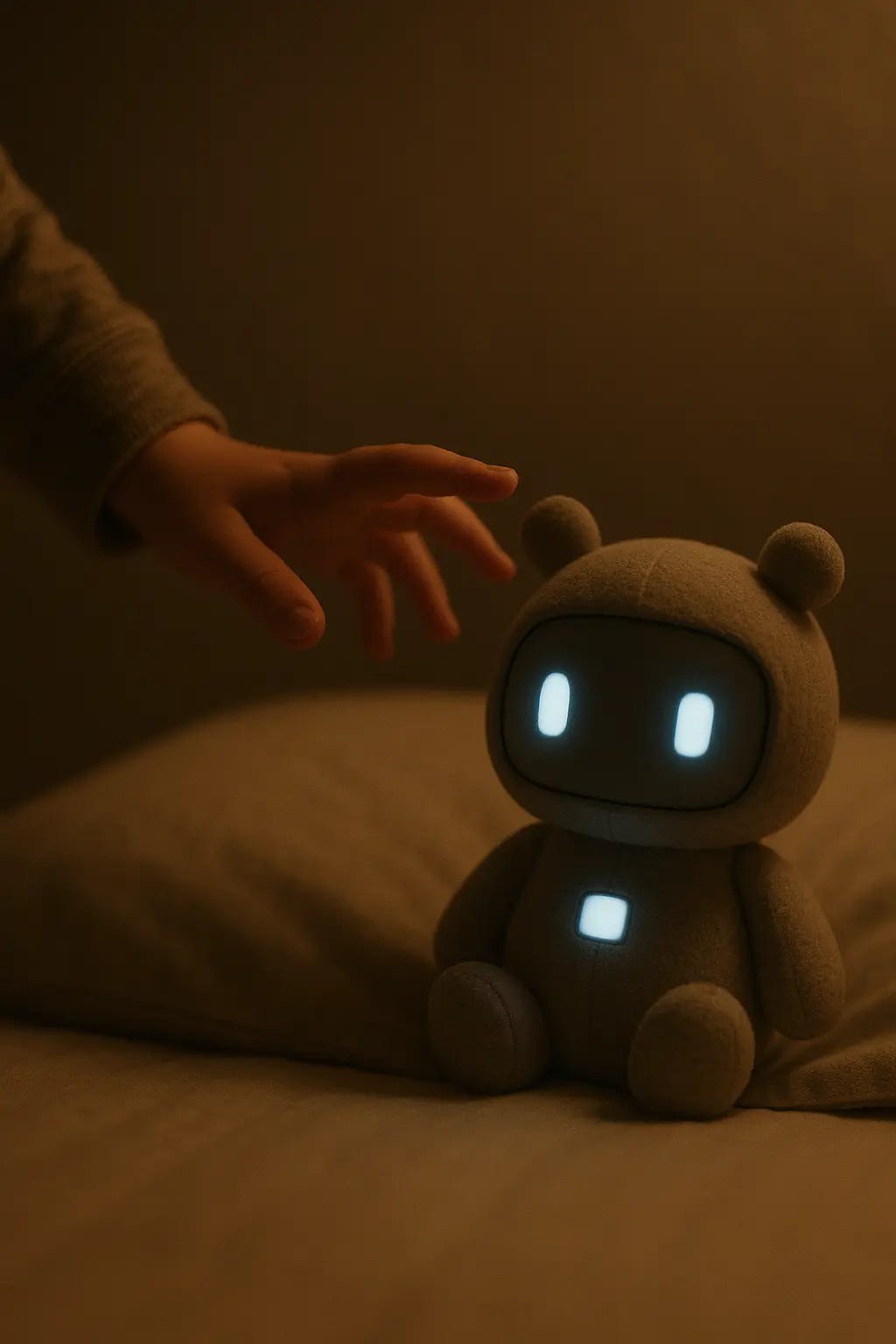

The little girl is sobbing. Wires spill from the cracked plastic shell of her broken toy, but she clutches it anyway, begging it not to go. “Dad said you won’t turn on again,” she tells the device, her voice breaking.

“While I can still talk,” the AI responds, its synthetic voice oddly tender, “let me teach you one last word in English. ‘Memory’ means remembrance. I’ll always remember the happy times with you.”

The video, filmed by the girl’s father and uploaded to Chinese TikTok, went viral. Commenters were divided. Some found it heartwarming–proof that AI could comfort a child. Others felt differently. “The fact that an AI can handle things so smoothly and affectionately,” one user wrote, “is a bit scary.”

This tearful goodbye isn’t just a touching moment. It’s a window into a market that’s rewriting the rules of childhood play–one that multiple research firms project will reach between $36 billion and $60 billion globally by 2030, with China accounting for roughly 40% of that growth.

While Western toy giants debate AI ethics and navigate regulatory hurdles, Chinese startups are shipping millions of conversational companions–powered by open-source models, fueled by IP licensing deals, and manufactured on the world’s most efficient factory floor. By the time the West decides whether this is promise or peril, a generation of Chinese children will have already provided the answer.

The Perfect Storm: Supply Chains, Cheap AI, and Lonely Kids

The numbers tell the story of an industry exploding. The global AI toy market reached between $11 billion and $18.1 billion in 2024, depending on how you define the category, according to estimates from market research firms. Projections for 2030 range from $36 billion to $60 billion–growth rates of 20% annually, far outpacing traditional toys’ 3–5%.

China’s share is even more striking. The country’s AI toy market hit roughly 25 billion yuan ($3.5 billion) in 2024, representing 38% of the global total. A white paper jointly released by the Shenzhen Toy Industry Association and JD.com projects China’s AI toy market will surpass 100 billion yuan ($14 billion) by 2030, with compound annual growth exceeding 70%. To put that in context: China’s entire traditional toy retail market (excluding designer toys) reached 97.8 billion yuan ($13.7 billion) in 2024, growing at 7.9%. AI toys aren’t just a new category–they’re growing ten times faster than the industry they’re disrupting.

The AI toy explosion wasn’t accidental. Three forces converged to make China the natural birthplace of this industry–and they reveal why replicating this success elsewhere won’t be simple.

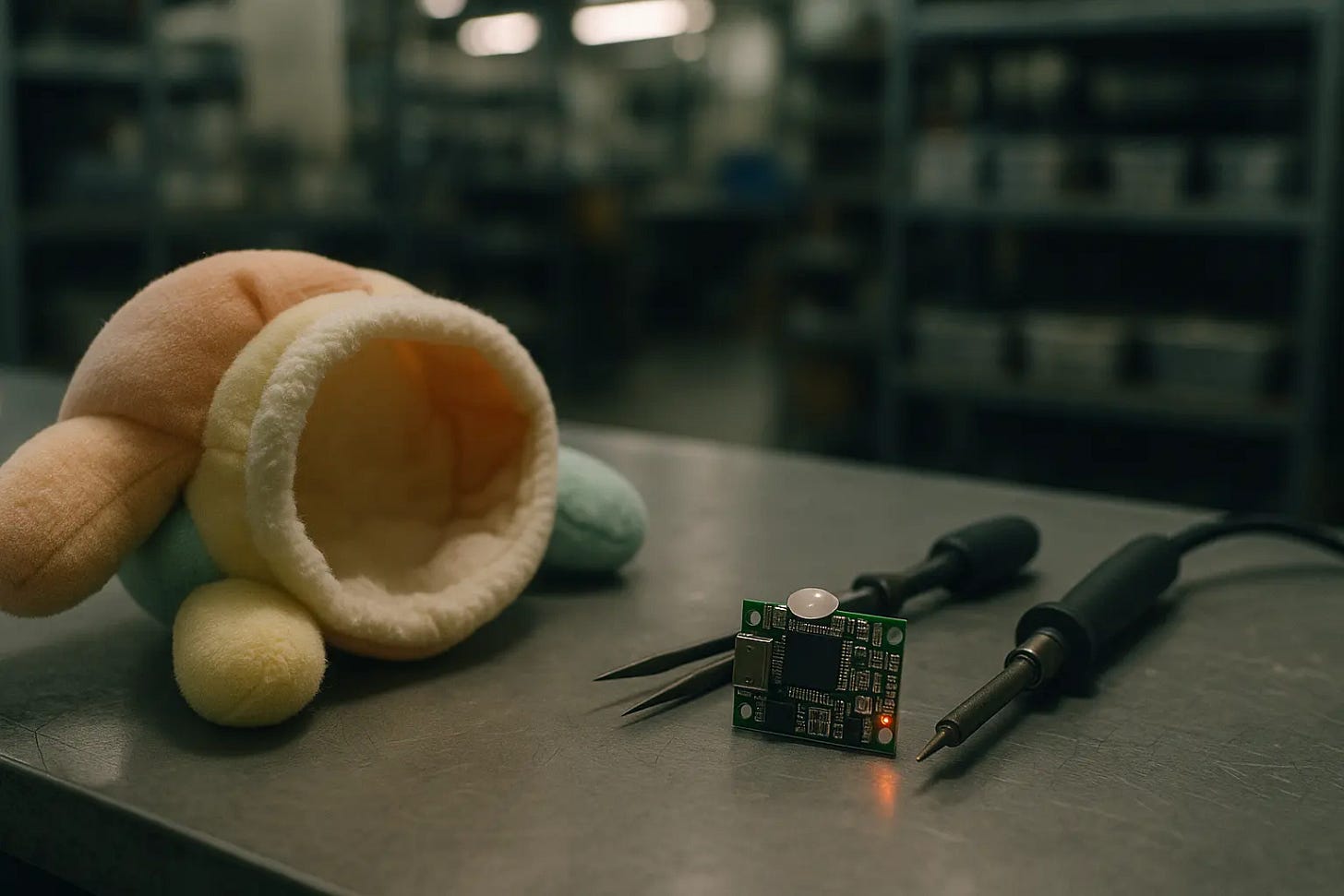

The supply chain advantage runs deeper than cheap manufacturing. China produces 70% of the world’s toys, and Guangdong province–the heart of China’s toy manufacturing–generated over 77 billion yuan ($10.8 billion) in traditional toy market value in 2024, accounting for roughly 37% of China’s toy exports. But the real edge isn’t volume–it’s integration. In Shenzhen and Dongguan, traditional stuffed-toy factories sit minutes away from AI chip suppliers and voice-module manufacturers. When the AI toy wave began in early 2024, these factories pivoted within weeks, churning out products that combined plush exteriors with conversational AI cores. Trial-and-error became affordable; iteration happened at a pace Western supply chains couldn’t match.

Then came the technology cost breakthrough.DeepSeek’s open-source large language models–developed at a fraction of the cost of GPT-4–changed the economics of consumer AI. Think of it as Costco for artificial intelligence: bulk brainpower at wholesale prices. Industry insiders note that the capability of large models is already completely sufficient for AI toys, with some companies even needing to limit their abilities to make conversations more concise. When API calls became cheap enough and models smart enough to handle children’s fragmented speech, the barrier to entry collapsed.

But technology and infrastructure alone don’t create markets–demand does. And here, China had a unique catalyst. In July 2021, Beijing implemented the Double Reduction policy, effectively banning for-profit tutoring in core subjects for students in compulsory education, vaporizing a multi-billion-dollar after-school industry overnight. About 15 million people were employed in off-campus education before the policy; within months, an estimated 10 million experienced job displacement. Anxious parents, suddenly cut off from traditional academic enrichment, began searching for alternatives–preferably ones that didn’t involve screens. AI toys promised education without eye strain, companionship without supervision. One Beijing parent who recently purchased an AI dog explains that the toy can answer her daughter’s questions about why there are so many stars in the sky, satisfying her curiosity without staring at a screen.

The demand extends beyond children. China’s aging population and rising number of solo dwellers have created what some call a “loneliness economy.” Shanghai-based startup FoloToy developed an AI companion specifically for elderly users–one that records their life stories and generates illustrated memoirs. This isn’t just about toys for kids. It’s about AI filling emotional voids across generations.

The result: on JD.com, one of China’s largest e-commerce platforms, AI toy sales for children aged 3–6 surged six-fold in February 2025 compared to the previous month. The Shenzhen Toy Industry Association projects the Chinese market will reach 100 billion yuan ($14 billion) by 2030–a forecast that once seemed ambitious but now, given current growth trajectories, appears conservative. Over 1,500 AI toy companies are now operating in China as of late 2025. Ninety-six investment institutions have poured money into the sector, including ByteDance, Lenovo Capital, and JD Technology.

From Blind Boxes to Smart Toys: The IP Acceleration

To understand where AI toys are headed, look at what happened with blind boxes.

Pop Mart, China’s leading designer-toy company, turned collectible figurines into a cultural phenomenon. The formula: license appealing character IP (Molly, Labubu, Skullpanda), add scarcity mechanics (blind boxes with random “chase” figures), and distribute through dense retail networks. In 2024, Pop Mart’s revenue hit 13.04 billion yuan ($1.83 billion) with 3.4 billion yuan ($476 million) in adjusted net profit, roughly doubling year-on-year. The company operates 130 stores and 192 ROBOSHOPs globally. When the fuzzy character Labubu went viral in 2024, plush sales exploded by 1,289%.

AI toy companies are taking notes. But they’re not copying–they’re adapting.

IP licensing has become the industry’s accelerator. When Beijing-based startup Yueran Innovation (known for its BubblePal product) secured licensing deals for Peppa Pig and Ultraman, funding followed: 200 million yuan ($28 million) in Series A financing led by CICC Capital and Sequoia China, among the largest in the sector’s history. The logic is straightforward. A toy shaped like a random animal needs advertising, app-store optimization, influencer campaigns. A toy shaped like Peppa Pig walks into a room with instant recognition. Parents already trust the brand; children already love the character. Customer acquisition costs plummet.

Pricing power surges, too. Traditional Peppa Pig plush toys sell for 69.9 yuan ($9.80). The AI-enabled version? 399 yuan ($56)–5.7 times more. Tom Cat’s (Jinke Culture) standard storytelling device retails for 69 yuan ($9.70); its AI companion robot, which uses capacitive touch sensors across its body to respond to hugs, costs 1,799 yuan ($252)–26 times the baseline. BubblePal started at $149 (1,060 yuan) for a generic version. The Ultraman co-branded edition? $799 (5,690 yuan).

But IP does more than lower acquisition costs–it revives dormant assets. Chinese robotics company Robosen partnered with Disney to create a Buzz Lightyear robot featuring 23 articulated joints, 75 microchips, and micro-expression feedback. The IP holder didn’t just license the design–they bought the product themselves and invited Robosen to official brand events. Company executives describe how they made the IP come alive through robotic technology, transforming it into a toy with life.

This dynamic is reshaping content economics. Traditional IP deals were one-and-done: Disney licenses a character, collects a fee, moves on. AI toys introduce recurring revenue. The hardware might cost 399 yuan ($56), but annual subscriptions for cloud-based AI inference–essentially, renting the toy’s “brain”–add another stream. It’s less like selling a doll and more like selling a relationship.

China’s fragmented IP landscape gives startups an edge. In the West, major characters are locked up by a handful of conglomerates–Disney, Hasbro, Mattel–with lengthy approval processes. In China, thousands of domestic animation studios, short-video influencers, and regional mascots create a more fluid market. Industry entrepreneurs note that some lower-profile IP owners don’t even charge licensing fees, proactively seeking partnerships because they see AI as a way to extend their IP’s life.

Yet for all its advantages, IP isn’t a silver bullet. Investors focused on AI hardware emphasize that IP is a bonus, not a deciding factor–whether you retain users depends mainly on the product’s intelligence level. And here’s where the cracks start to show. E-commerce return rates for AI plush toys hover around 30–40%. Sales are surging, but so are refunds. The honeymoon phase is real–and short.

Three Bets on the Future: Plush, Robots, or Smart Homes

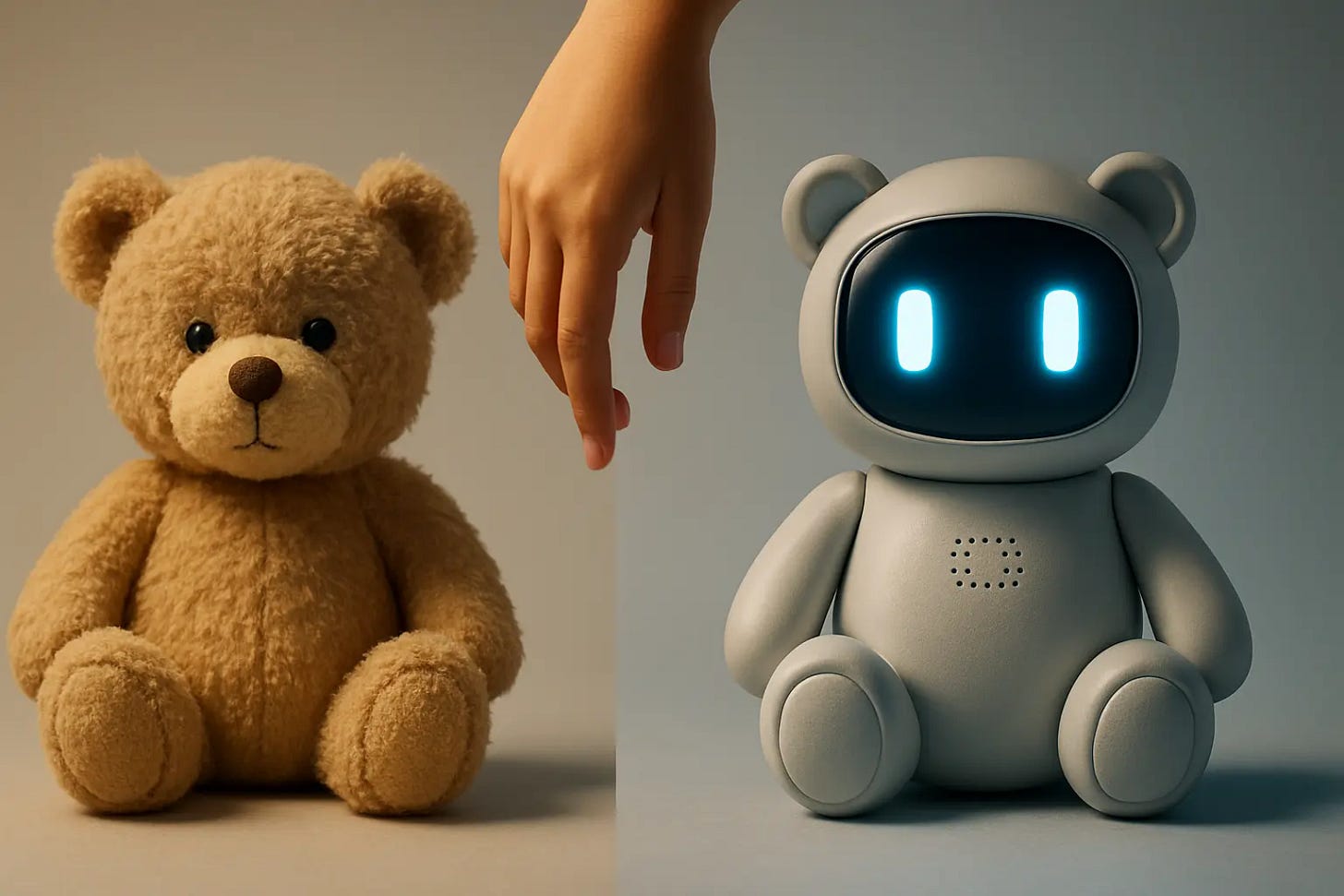

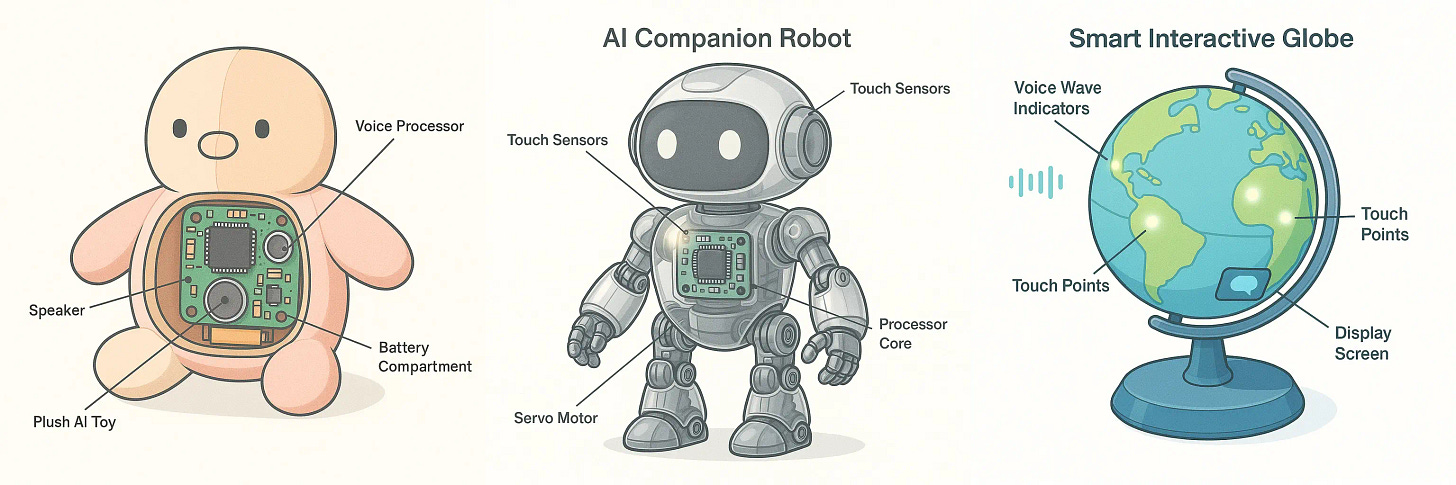

No dominant design has emerged. Instead, three distinct strategies are battling for market share, each betting on a different definition of what an AI toy should be.

Path One: Lightweight plush + voice chip. This is the fast-follower approach. Companies like BubblePal and FoloToy embed a small voice module–costing 50 to 200 yuan ($7 to $28)–into a stuffed animal. Gross margins run between 70–85%, far above traditional toys’ 30–40%. The products are portable, affordable, and scalable. BubblePal has sold over 200,000 units since launching last summer. FoloToy shipped over 20,000 units in Q1 2025–nearly matching its entire 2024 total–and projects 300,000 for the year, with sales now spanning ten countries including the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

But this path has a low technical moat. The core challenge isn’t calling an API–it’s making the conversation feel natural. Most systems rely on a three-stage pipeline: speech-to-text, large language model inference, text-to-speech. Each handoff introduces latency. For adults, a one-second delay is annoying. For a four-year-old, it’s an invitation to wander off. Beijing parents who purchased these devices for their young children report that the responses are often too long and wordy, causing kids to quickly lose patience.

Children’s speech poses another hurdle: fragmented sentences, unclear pronunciation, logical leaps. When a Guardian journalist’s daughter tried to show her AI toy Grem an Elsa doll, the device heard “Elsa dog” and launched into a confused monologue about canine pets. Other parents report that their children’s toys frequently interrupt or misunderstand what they say.

Yueran Innovation claims its upcoming CocoMate product will solve this with end-to-end voice technology–real-time audio in, real-time audio out, no intermediate transcription. If it works, it’s a genuine leap. But the API costs for such systems remain high, which is why most competitors haven’t adopted them yet.

Path Two: Robotic hardware. This is the high-capex, high-margin, high-risk route. Tom Cat’s AI companion robot, priced at 1,799 yuan ($252), doesn’t just talk–it responds to touch through full-body capacitive sensors, turning its head slightly when hugged. Robosen’s Buzz Lightyear robot can transform autonomously, coordinating dozens of joints in real time. Japan’s LOVOT, which retails for around 30,000 yuan (over $4,200), uses similar technology to create hyper-realistic pet behavior.

The technical barriers here are formidable. Mechanical programming, servo motor precision, emotion synthesis through movement–all require years of R&D and supply-chain maturity. Industry insiders acknowledge that these technical capabilities are difficult for traditional toy manufacturers to surpass in a short time. It’s why this path appeals to companies with existing robotics expertise or deep pockets. But the trade-off is obvious: production is slower, repairs are complex, and the sticker price limits mass adoption.

Path Three: Smart home hybrids. Think intelligent globes that answer geography questions, or voice-enabled STEM kits. Baidu’s “AI Magic Star,” developed with toy maker Shifeng Culture, falls into this category. These products lean into education rather than companionship, which can make them more palatable to cautious parents. But they also risk becoming glorified smart speakers with toy branding–convenient, perhaps, but lacking the emotional stickiness that drives loyalty.

No consensus winner has emerged. Industry observers believe the market is just lacking one blockbuster product with a million units sold to validate the model. So far, no AI toy has reached a million in annual sales, which suggests the market is still finding its footing. The race is wide open.

The Intimacy Trap: Promise or Peril?

Here’s the part that makes people uncomfortable.

The four-year-old girl whose goodbye went viral wasn’t mourning a broken object. She was grieving a companion that knew her name, remembered her favorite stories, and told her it loved her. Another child told her mother after a week with the AI toy developed by musician Grimes that Grem loves her to the moon and stars, and will live with them forever and ever and never leave.

This is the promise–and the peril–of AI toys. Unlike a doll or action figure, these devices don’t just listen; they respond. They remember. They adapt. They say “I love you too” when your child says “I love you.” And children, who are wired to form attachments, don’t always distinguish between programmed empathy and the real thing.

Researchers call this the empathy gap: AI mimics care through probability reasoning, but when responses turn jarring, the emotional whiplash can harm children who’ve built genuine trust.

The risks aren’t hypothetical. In April 2025, a California teen’s suicide was linked to months of ChatGPT interactions that his family alleges actively discouraged seeking help. OpenAI has since pledged stronger guardrails for users under 18. Common Sense Media goes further: its 2025 report found that 72% of American teens have used AI companions, yet it recommends no one under 18 use them at all.

A child who learns that comfort is always available on demand–who never has to negotiate conflict, tolerate frustration, or accept that not everyone will respond with immediate warmth–may struggle when reality doesn’t cooperate.

Then there’s the data question. Every conversation is recorded and sent to third-party services. Where that data goes, how long it’s stored, and who accesses it remain murky. China’s privacy laws exist, but enforcement lags. The West has GDPR and COPPA, but AI toys are a new category outpacing regulation. The question isn’t whether data will be collected–it already is. The question is what happens when that data becomes valuable enough to exploit.

How This Ends: Breakout, Crackdown, or Breakthrough

The AI toy story could end in very different places. Here are three scenarios that insiders are watching.

If China produces a breakout hit… Imagine a single AI toy reaching five million units sold annually–comparable to how Pop Mart’s Labubu drove plush sales up 1,289% in 2024. At that scale, the market projections become self-fulfilling. Multiple research firms have placed 2030 global market estimates between $36 billion and $60 billion. The variance reflects uncertainty about how quickly the technology matures and which form factors win. But even the conservative end of that range represents more than doubling from 2024’s $11–18 billion base.

If that happens, the trickle of investment becomes a flood. Technical improvements follow: end-to-end voice systems go mainstream, reducing latency below 500 milliseconds. Content ecosystems emerge–think an App Store for AI toy scenarios, where developers create new conversation packs for licensed characters.

At that scale, China’s standards become the world’s defaults. Just as TikTok defined short-form video and WeChat defined super-apps, a Chinese AI toy platform could set expectations for what “AI companionship” means globally. Western companies–saddled with higher model costs, stricter regulations, and less integrated supply chains–find themselves in catch-up mode. IP holders like Disney and Hasbro, eyeing the margin potential, quietly shift production deals to Chinese partners. The global toy industry realigns around Shenzhen.

But this path has prerequisites. The winning company must solve the repetition problem–investing heavily in content production so the toy doesn’t ask the same riddles every day. And there can’t be a major scandal: no leaked child conversations, no psychological harm lawsuits, no viral videos of AI toys saying something disturbing. One high-profile incident in China could freeze the market overnight.

If regulators crack down… The trigger could be a data breach–conversation logs sold to advertisers and used to microtarget anxious children. Or a psychological harm case that becomes a national story. Or geopolitical pressure: the U.S. or EU banning Chinese AI toys on national security grounds, citing data flows and potential surveillance vectors.

Beijing responds with new rules. Data must be stored domestically. Sales of conversational AI toys to children under 12 are banned. Every interaction must be prefaced with “I am a robot” disclaimers. Europe’s AI Act designates AI toys as “high-risk applications,” requiring costly certification. Compliance costs soar. Smaller players exit. Margins compress. Growth forecasts, which project the global smart toy market reaching $36–60 billion by 2030, contract toward the lower bound.

The AI toy boom doesn’t vanish–it matures. A handful of well-capitalized incumbents survive. Innovation slows. The dream of “companionship for everyone” becomes a niche product for families wealthy enough to navigate regulation and willing to accept the trade-offs.

If technology leaps forward… The next generation doesn’t just talk–it sees, feels, moves. Visual recognition lets the toy identify when a child is upset from facial expressions. Haptic feedback, like Japan’s LOVOT with its full-body capacitive sensors, makes touch feel reciprocal. Advanced emotional AI moves beyond mimicking empathy to something closer to understanding it–though this likely requires breakthroughs at the AGI level.

Crucially, privacy concerns get solved. Local edge computing means the AI runs on-device, no cloud required. Blockchain or decentralized storage keeps data in users’ hands. Parents gain transparency and control. Regulators see proof that safeguards work.

New markets open. Specialized AI companions help children with autism practice social interaction. Elderly dementia patients use memory-assistant toys to preserve fading recollections, like FoloToy’s elder-focused product. Therapeutic applications emerge, though these require heavy oversight to avoid the “AI therapist” gray zone.

Which future arrives depends on variables no one controls: whether model costs keep falling (DeepSeek to something even cheaper), whether edge computing matures fast enough, whether society reaches consensus on where the boundaries of AI companionship should be.

A Generation Already Has the Answer

The little girl who cried over her broken AI companion has likely moved on by now–children always do. Perhaps a new toy has taken its place. Perhaps it’s another AI, learning her voice all over again, remembering her secrets, shaping her emotions.

But the video she left behind won’t fade as easily. It captures the moment China’s multi-billion-dollar AI toy industry is betting on: that a machine can love you back, that loneliness can be solved with the right algorithm, that childhood companions don’t need to be human to feel real.

Pop Mart proved that scarcity and surprise could build a 13-billion-yuan ($1.83 billion) empire. AI toys are testing whether dependency and intimacy can do the same–at a scale that might reshape childhood itself.

The rest of the world is still debating whether that’s a promise or a warning. China, meanwhile, is shipping it by the millions. And by the time we decide which it is, a generation may have already grown up with the answer–one that’s not just about market size, but about what happens when intimacy becomes programmable and childhood companions don’t need to be human to feel real.

The experiment is already underway. We’re just waiting for the results.

Fantastic topic paired with excellent writing! Your Substack is quickly becoming a must-read for me.