China's Fast-Follower Trap: The Cost of Execution Excellence

China’s AI leaders reveal what really worries them (it’s not execution).

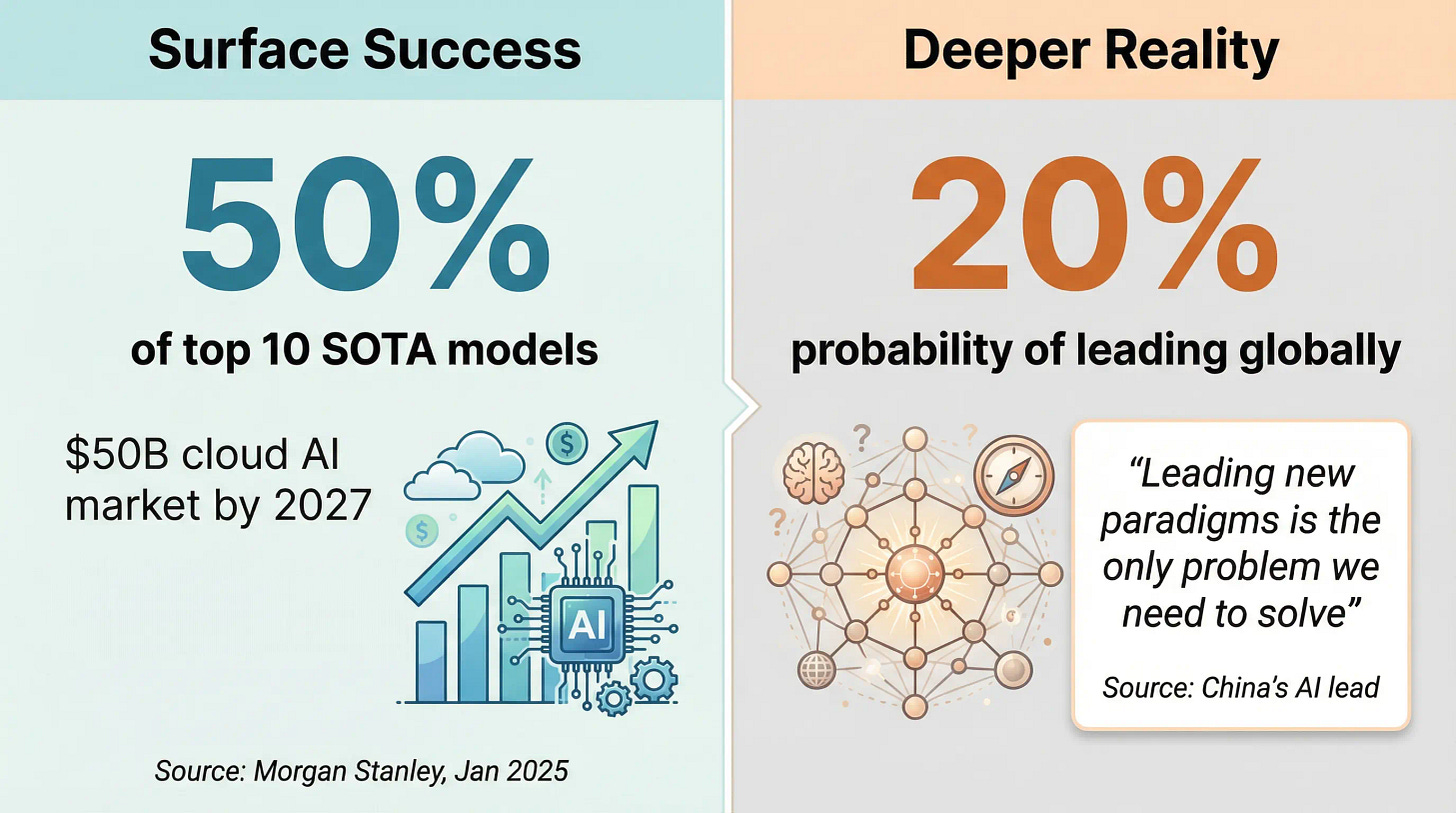

Morgan Stanley released a bullish report on China’s AI sector on January 8th. The numbers look impressive. Chinese companies now claim half of the world’s top 10 state-of-the-art foundation models. The investment bank projects China’s cloud AI market will reach $50 billion by 2027. These figures suggest a classic catch-up story. China is closing the gap with Silicon Valley through engineering prowess and massive capital deployment.

But two days later, something unusual happened. Four of China’s most important AI leaders gathered at Tsinghua University for a closed-door summit. The attendees included Yao Shunyu, former OpenAI researcher now serving as Tencent’s Chief AI Scientist. Lin Junyang leads Alibaba’s Qwen model development. Yang Zhilin founded Moonshot AI, which just raised $500 million. Tang Jie runs Zhipu AI, which went public in Hong Kong the same week. (The full roundtable transcript is available here; it's in Chinese, so bring your translation tool.)

These leaders had direct access to China’s AI progress. They understood the technical achievements better than any outside analyst. Yet their self-assessment was strikingly different from the optimistic headlines. Lin Junyang put the probability of a Chinese company becoming the global AI leader in three to five years at just 20%. Yao Shunyu identified a single critical challenge. Leading new paradigms was the only problem China needed to solve, he said. The other issues were already handled. Engineering, business execution, product design. China had those covered. What remained was the hardest part.

This disconnect reveals something important. China’s AI sector faces a challenge that goes beyond compute resources or algorithm improvements. The same factors that enable rapid execution within established paradigms create structural barriers to leading paradigm shifts. Being very good at following makes it harder to lead.

What China’s AI Leaders Actually Fear

The summit conversation offered rare candor about China’s AI development. These leaders weren’t discussing technical benchmarks or model parameters. They focused on something more fundamental. Can Chinese companies define the next generation of AI capabilities rather than implement what others have proven?

Yao Shunyu framed the challenge directly. China already surpassed the US in engineering, business, and product design, he noted. DeepSeek’s efficient training methods and the rapid proliferation of open-source models demonstrated real technical competence. Chinese companies could take a proven concept and execute it faster, cheaper, and often better than the original. That skill was valuable but insufficient.

What mattered was something else. Could these companies invest years of research into directions that might fail? Could they sustain exploration when commercial pressure demanded immediate results? Yao’s diagnosis was blunt. China preferred safer approaches. When faced with uncertain projects like long-term memory or continual learning, teams hesitated. They didn’t know how to approach the problem. They didn’t know if success was possible. That uncertainty made commitment difficult.

Tang Jie described the time pressure his company faced. Getting the code right might lead to success, he said. But failure could mean losing six months. Those six months could be everything. Market windows closed fast. Competitors moved quickly. Capital demanded results. A detour into unproven research could mean missing the entire opportunity.

Lin Junyang’s 20% estimate made sense in this context. He wasn’t questioning technical capabilities. He was recognizing systemic constraints. Market dynamics rewarded execution but punished exploration. Chinese AI companies operated in an environment that filtered for one type of success and against another.

The Silicon Valley contrast was clear. Anthropic built Claude for years without monetization pressure. OpenAI maintained research focus after ChatGPT’s success. Their funding structures allowed long-term bets. Chinese companies faced different pressures. The difference wasn’t about ambition or talent. It was about what each system could sustain.

This raises an urgent question: Why does this system exist? And more importantly, can it change? The answer lies in how capital actually flows through China’s AI ecosystem.