Stress Test in China’s AI-Chipland: Life Beyond Geopolitical Arbitrage

Hello China Tech by Poe Zhao – Weekly insights into China’s tech revolution. I analyze how developments in Chinese AI, electric vehicles, robotics, and semiconductors are reshaping global technology landscapes. Each piece contextualizes China’s innovations within worldwide market dynamics and strategic implications.

In the high-stakes chess match of the US-China technology rivalry, policy decisions are the pivotal moves, capable of reshaping market landscapes overnight. One such move just landed on the board, sending immediate and complex reverberations from Silicon Valley to Shanghai, and putting an entire industry to the test.

On July 15, a policy reversal in US trade sent tremors through the global technology sector. Nvidia and AMD confirmed they had received assurances from Washington to resume sales of their China-specific AI accelerators—Nvidia’s H20 and AMD’s MI308, both designed to comply with US export rules.

The decision ended a three-month halt, initiated by a US ban in April, on products that had already been selling into the Chinese market. For Nvidia, the move was a notable success for its chief executive, Jensen Huang, who had lobbied intensely against the restrictions.

Yet beyond the immediate market rally, the decision marks a new, more intense phase of a stress test for China’s nascent GPU industry. The three-month absence of the H20 was not a pause but a market catalyst. It created a window for domestic AI chipmakers, who saw their order books swell as China’s tech giants, deprived of their preferred Nvidia hardware, were forced to accelerate their adoption of local alternatives.

This was the moment their business model—a form of “Geopolitical Arbitrage” that turns US restrictions into a competitive moat—was put into practice. With the return of the H20, these domestic champions, fresh from a period of real-world market validation, must now face their primary rival head-to-head. The central question for investors and policymakers is clear: After a period of protected growth, can they now truly compete?

A Crack in the Moat

The Geopolitical Arbitrage model rests on two foundational pillars, both of which were reshaped during the H20’s absence. The first is the captive customer. The state-led “Xinchuang” (信创, an IT application innovation initiative to replace foreign tech) has long provided a reliable revenue stream. The three-month ban, however, expanded that captive audience.

During that window, according to multiple local industry sources, major domestic chipmakers like Kunlunxin and Cambricon saw their “capacity fully booked” with “exploding orders.” This was not just the traditional “Xinchuang” market. Major cloud vendors and data centers, who had previously only tested domestic chips as a backup plan, began deploying them in their actual operations.

This period allowed domestic products to move from lab tests to real-world scenarios, providing invaluable feedback for product iteration. As a Tencent executive noted in a May earnings call, the company was evaluating both imported and domestic chips—signaling a strategic shift toward a dual-sourcing reality.

Nvidia’s return now complicates this new dynamic. While the most security-sensitive government entities will likely maintain a strict “buy domestic” policy, the wider range of customers who were forced to adopt local solutions now face a more nuanced choice. The moat of a guaranteed market, once broadened by the ban, now has its first significant crack.

This new reality also complicates the second pillar of the arbitrage model: the rush to the public markets. For China’s cash-burning GPU unicorns, an IPO has been framed as a matter of survival. The H20’s re-entry makes this “IPO or die” narrative a double-edged sword.

On one hand, the need for capital is more acute than ever to fund a sales war against a formidable competitor. On the other, their investment story has become harder to sell now that the prospect of direct competition with Nvidia is a reality, potentially complicating their access to the very capital needed for survival.

The “Good Enough” Revolution on Trial

The core of the stress test will take place in the open market, where the “Good Enough” strategy of Chinese chipmakers faces its first true trial. The three-month ban was not just a sales opportunity; it was a period of intense, forced collaboration between domestic GPU vendors and their new clients. This accelerated the development of the domestic software ecosystem as hardware and software were jointly debugged and optimized for specific workloads.

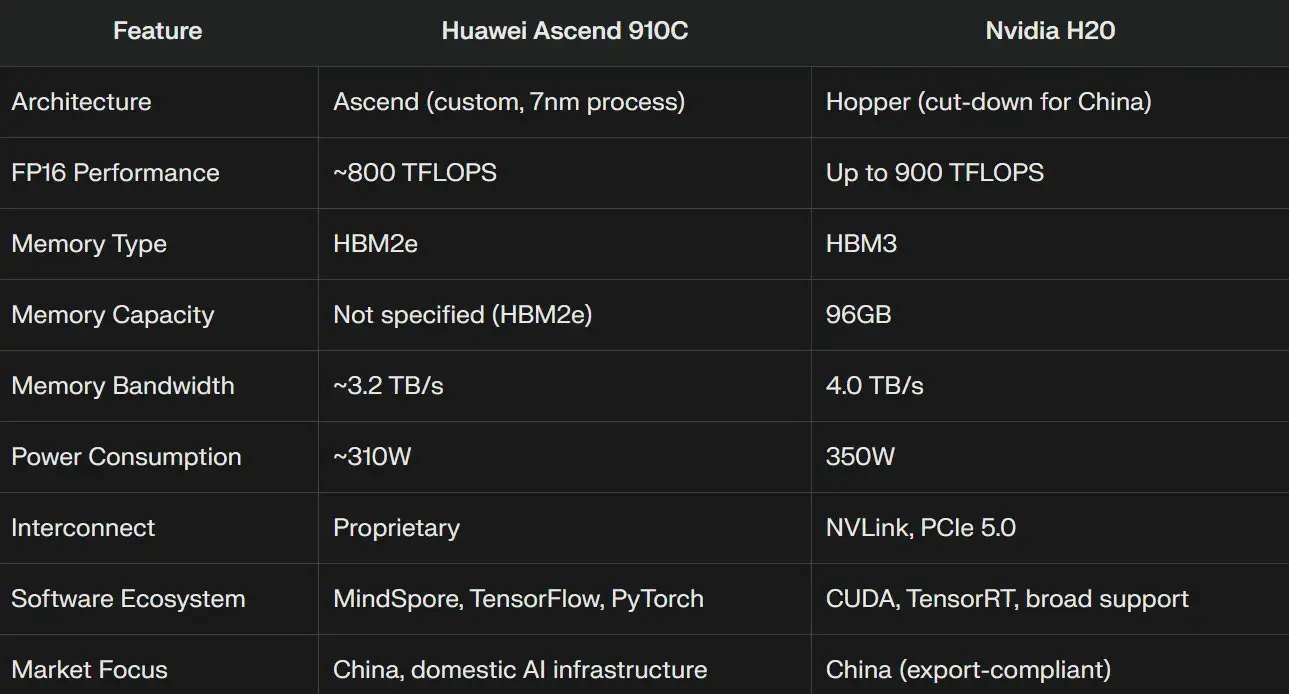

The objective for domestic firms was clear: develop products that could serve as direct “pingti” (平替, a term for affordable alternatives) for the H20. Companies have launched a slate of contenders, including Kunlunxin’s P800, Moore Threads’ MTT S80, and Huawei’s Ascend 910C, all explicitly targeting the H20’s performance and price point.

Now, the question is no longer whether a domestic chip is “good enough” in isolation, but whether it offers better value than the H20. This battle will be fought on the terrain of price, performance, and Total Cost of Ownership (TCO).

The decision for a buyer like Tencent or ByteDance—both of whom have tested domestic chips while also placing large orders for the H20—will now be based on months of real-world operational data, not just lab tests. This is where Nvidia’s advantage becomes most pronounced. The H20, while less powerful than its unrestricted siblings, is a native citizen of the CUDA ecosystem. For a company whose entire AI development pipeline is built on Nvidia’s software stack, deploying the H20 is a relatively seamless process.

Adopting a domestic alternative, even after three months of intense integration work, still involves costs associated with running a dual-stack environment. The “Good Enough” revolution is no longer a theoretical concept; it is now a line item on a procurement manager’s spreadsheet and it will be scrutinized accordingly.

The Walls Get Higher

The new competitive dynamic does not just test the business models of Chinese firms; it also amplifies the two fundamental technical barriers they face. The “Two Walls”—Manufacturing and Ecosystem—have effectively become higher.

First, the Ecosystem Wall. With the performance gap between the H20 and top domestic chips narrowing, Nvidia’s CUDA software platform becomes an even more decisive differentiator. When hardware is comparable, the battle shifts to software. The forced collaboration during the ban gave the domestic ecosystem a boost, but it is still a nascent effort compared to CUDA, which is the result of more than 15 years of investment.

With the H20 now offering a familiar, stable, and powerful software environment, the incentive for Chinese developers to deepen their commitment to a parallel domestic ecosystem is diminished.

Second, the Manufacturing Wall. US sanctions have effectively cut off Chinese chip designers from the world’s most advanced semiconductor fabrication nodes, primarily those operated by TSMC. Chinese foundries like SMIC remain years behind. This forces Chinese designers into a difficult compromise: they can design a powerful chip on paper, but they must have it produced on a lagging, less efficient process—creating a permanent performance-per-watt disadvantage.

The return of the H20, produced on a mature and efficient node, throws this handicap into sharp relief. The pressure on China’s domestic foundry industry to accelerate its progress has become immense.

A New Equilibrium

The stress test initiated by the H20’s return is unlikely to kill China’s domestic GPU industry. The political will, committed capital, and the market traction gained during the three-month window are too substantial. Instead, the competition will harden the industry, forcing it to specialize and prove its value proposition.

The likely outcome is the solidification of a “Dual-Track” market, not as a theoretical construct, but as an equilibrium forged in the fires of competition. One track will be dominated by Nvidia, serving performance-sensitive pragmatists among China’s tech giants. The other track will be the domain of domestic champions, serving the security-focused compliance market and carving out niches where their TCO is genuinely advantageous.

As projected by the research firm TrendForce, domestic suppliers could still capture up to 40% of China’s AI server chip market by 2025, a testament to the scale of this protected track.

For observers trying to gauge the outcome of this new phase, the key signals have shifted. The focus should move beyond raw performance claims and IPO valuations to the tangible metrics of market competition:

The Price War: The degree of discounting will be the clearest indicator of market pressure. Are domestic firms using price as their primary lever to compete with the H20, and can their margins sustain it?

Commercial Wins vs. State Orders: The most critical metric will be the customer mix. Is there a discernible trend of commercial, non-state-affiliated companies choosing domestic GPUs in a head-to-head contest with the H20?

The Ecosystem Race: The long-term determinant of success will be software. Are Chinese firms attempting to build a completely new, isolated island, or are they building “bridges” to the CUDA mainland through compatibility layers and open-source frameworks?

The era of Geopolitical Arbitrage as a standalone business model is over. For China’s AI chipmakers, the stress test has begun. Their survival now depends not on the protection of their government, but on their ability to compete.

About Hello China Tech

I’m Poe Zhao, and I bridge the gap between China’s rapidly evolving tech ecosystem and the global community. Through Hello China Tech, I provide twice-weekly analysis that goes beyond headlines to examine the strategic implications of China’s technological advancement.

Found this useful?

→ Share this newsletter with colleagues who need to understand China’s tech impact

→ Subscribe for free to receive every analysis:

→ Follow the conversation on 𝕏 for daily updates and additional insights

Get in touch: Have questions about China’s tech sector or suggestions for future analysis? Reply to this email – I read every message.