Why ByteDance Keeps Denying Its AI Glasses

10,000 units leaked. Company denies. New details emerge. The contradictions reveal sophisticated risk management.

ByteDance’s AI glasses story keeps changing. Reports emerged in early January that the company planned to ship 10,000 units at under $300, using Qualcomm’s AR1 chip. Details leaked about partnership with Longcheer Technology, a Chinese contract manufacturer, for hardware development. Then ByteDance denied everything. “No clear sales plan,” the company said.

The next day brought new reports. The 10,000 units would target “senior Doubao users”–experienced customers of ByteDance’s AI assistant. No public sale. A second generation was already in development. ByteDance again pushed back. A source told Beijing Business Today the sales planning reports were inaccurate.

Meanwhile, OpenAI spent $6.5 billion to acquire Jony Ive’s design firm and hired over 20 Apple hardware engineers. CEO Sam Altman describes the forthcoming device as feeling “peaceful like a cabin by the lake.” Yet the company is building infrastructure for audio-first hardware, exploring speakers and glasses. Meta pushes Ray-Ban AR glassesemphasizing “low interference.” Alibaba hedges with browser-layer AI through Quark and vertical devices for specific use cases.

The pattern looks chaotic. Companies contradict themselves. Strategies shift. No one commits publicly to a specific vision. The real game being played is different from what the surface suggests.

Building Capabilities Without Picking Winners

The apparent confusion reveals a deeper contest. Companies are competing on who can manage platform uncertainty most effectively.

Consider ByteDance’s behavior. The company acquired PICO for roughly $9 billion in 2021. It bought Smartisan phone assets. It launched an AI phone with ZTE’s Nubia sub-brand that sold out in 47 minutes. It released Ola Friend AI earbuds. Now it’s testing AI glasses. That’s four different hardware formats.

The 10,000-unit cap for glasses signals strategic intent. ByteDance can manufacture at massive scale. For a company that moves fast and scales aggressively, 10,000 units means testing, not launching. Large enough to generate learning. Small enough to abandon without consequence.

The denials carry equal weight. The multi-format strategy reveals what ByteDance actually values. Phones, earbuds, glasses–the common thread is Doubao AI, not ByteDance branding. The company is competing for the interaction layer, not hardware market share. Hardware serves as a means to that end.

This explains the contradictions. ByteDance is building capabilities across multiple formats while preserving strategic flexibility. Heavy investment in potential. Minimal public commitment to specifics. When you don’t know which platform wins, excessive visibility creates vulnerability.

OpenAI faces the same challenge. Altman’s “peaceful cabin” vision sounds simple. The execution reveals complexity. Acquiring Ive’s entire design firm for $6.5 billion signals serious intent. Raiding Apple for 20+ hardware engineers across industrial design, camera engineering, chip development, and supply chain management builds comprehensive capability.

Yet OpenAI still won’t specify the format. Reports suggest “screenless” and “pocket-sized.” Altman emphasizes the device will filter information and operate with contextual awareness over long periods. Whether it’s a pendant, a clip, or something else remains undefined. The company promises launch in under two years. The vagueness serves a purpose.

The pattern repeats globally. Meta’s Ray-Ban glasses emphasize lightness and daily wearability over powerful compute. The company deliberately avoids the Vision Pro approach of high-capability, high-immersion. Instead, Meta positions its glasses as “low interference, high availability.” This sounds modest. The positioning preserves options.

The Promise That Creates New Lock-In

The platform ambiguity creates another tension. Even as these devices promise to eliminate app dependency, they generate new forms of control.

The industry vision claims AI devices will handle tasks without requiring users to navigate multiple applications. Just speak your intent. The AI figures out execution.

ByteDance’s Doubao phone assistant, launched in partnership with ZTE’s Nubia brand, demonstrates this approach. Spot a product on Xiaohongshu, China’s social commerce platform. The AI comparison-shops across platforms, finds the best price, and completes checkout. You only confirm purchase and payment. The experience collapses multiple apps into one interaction flow.

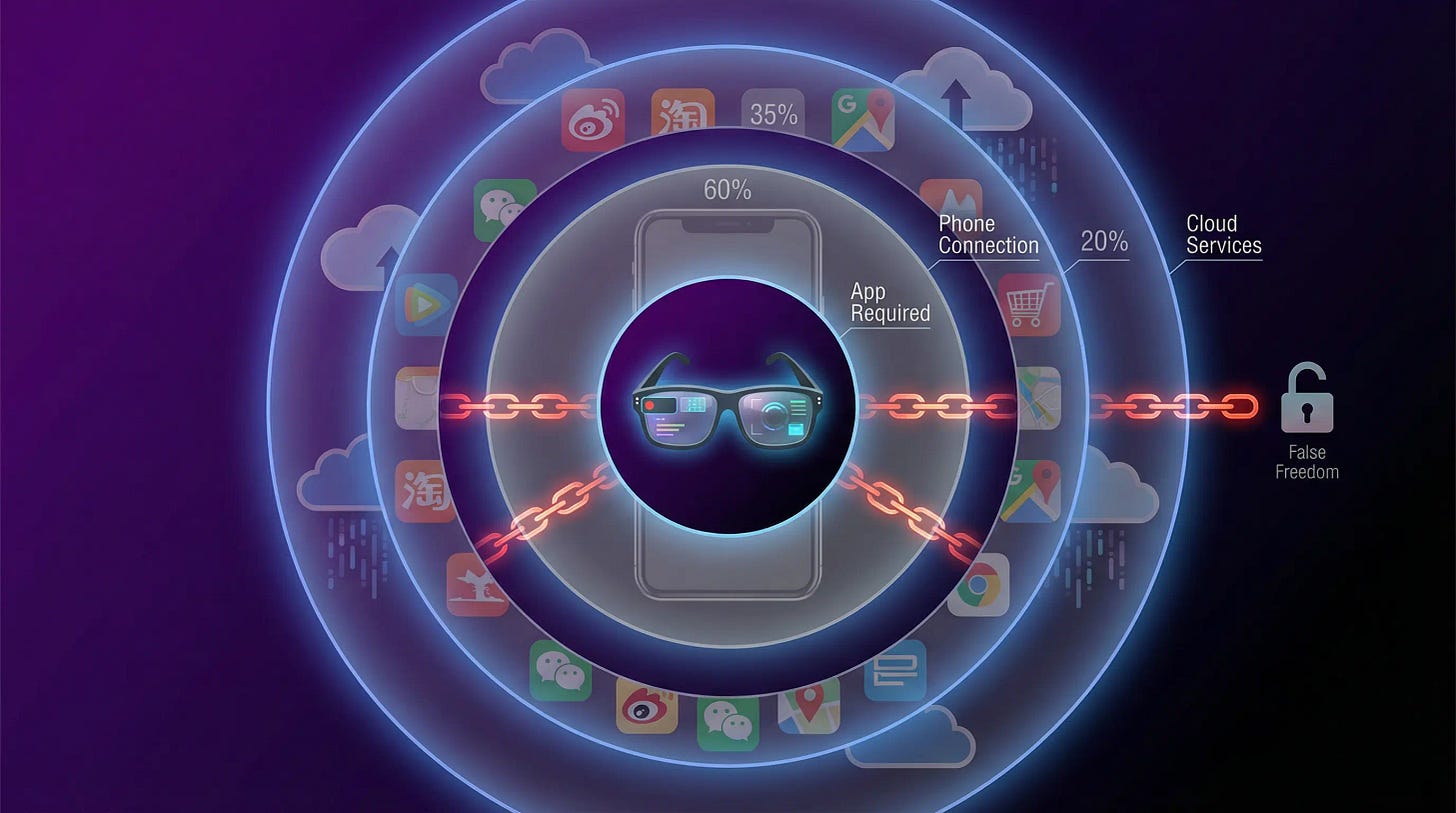

But here’s the contradiction. ByteDance’s AI glasses require the Doubao app to function. The promised elimination of apps creates new app dependency. The glasses don’t replace smartphones. They extend them.

This matters because it reveals the actual value capture mechanism. ByteDance isn’t trying to replace phones. The company is trying to own the interaction layer across devices. The glasses become another Doubao endpoint. Same with earbuds. Same with the phone’s system-level AI assistant.

ByteDance learned these constraints in China’s mobile platforms. The company discovered that ecosystem control trumps technical capability. When WeChat and other super apps control access, even successful AI agents face structural barriers. Hardware offers a potential alternative path–if the winning format can be identified.

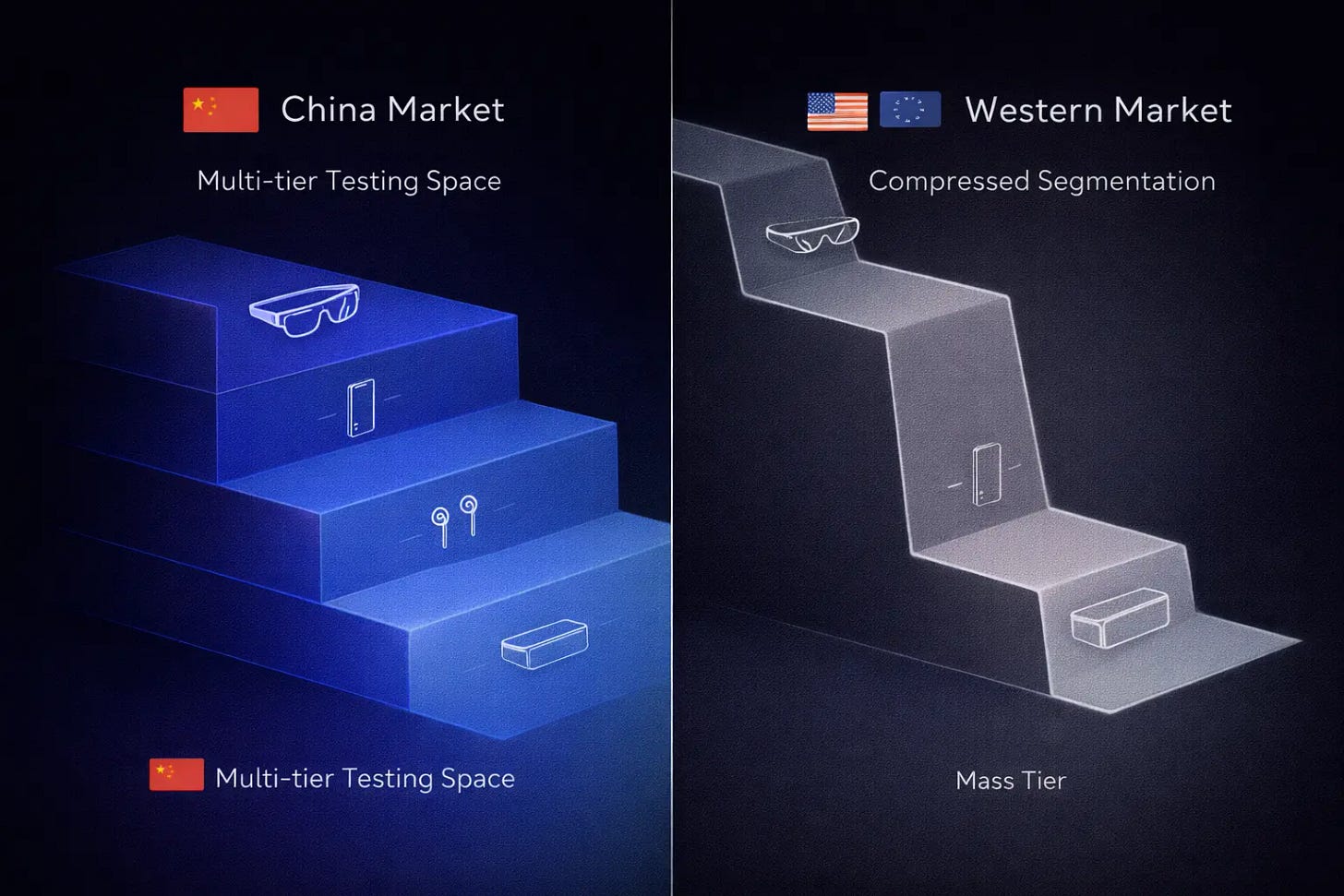

The strategy works in China’s multi-tier market structure. Different formats serve different use cases and user segments. AI glasses for visual queries. Earbuds for audio interaction. Phones for complex tasks. ByteDance can test all three because China’s market depth supports parallel experimentation.

Western companies face tighter constraints. OpenAI lacks an existing user base to test with. It must build from zero. Meta has users but faces platform limitations. Its Ray-Ban glasses still depend on smartphone connectivity for processing. Standalone AI devices remain distant.

The elimination of apps also threatens existing businesses. Uber and DoorDash built empires on keeping users in their apps. Serving ads, upselling services, building loyalty. If AI agents handle ordering, these companies lose direct user relationships.

Some resist. Amazon sued Perplexity over a shopping agent that scraped its site. Uber initially refused API access to Rabbit’s R1 device. The tension is real. Companies without control over the agent layer risk becoming commodified infrastructure.

Others cooperate cautiously. DoorDash, Instacart, and Expedia built integrations for ChatGPT. Ticketmaster, Uber, and OpenTable launched for Alexa+. They’re hedging. Participating enough to learn. Holding back enough to preserve options.

China’s Trial-and-Error Advantage

IDC forecasts 2.9 million smart glasses units in China for 2025, up 120% year-over-year. The growth stems less from superior technology than from market structure that enables faster experimentation.

Multi-tier markets create trial-and-error space. First-tier cities absorb premium devices. Lower-tier markets accept cheaper, less-capable versions. Companies can test multiple price points and capability levels simultaneously. Failure in one segment doesn’t kill the entire approach.

ByteDance can afford strategic ambiguity because of this structure. The 10,000-unit glasses test targets premium users. If it works, scale up. If not, the investment is contained. Meanwhile, the ZTE AI phone tests a different segment. Ola Friend earbuds test a third. Each experiment generates learning without requiring full commitment.

Western markets provide different testing dynamics. Market segmentation exists but compresses into fewer tiers. Companies can experiment, but parallel format testing faces higher coordination costs. The middle ground exists, it’s just harder to occupy profitably at scale.

The company doesn’t need its logo on every device. It needs its AI to become the default interaction layer. Hardware diversity becomes an asset rather than confusion. Each format tests where users will engage with Doubao.

Government’s role amplifies this dynamic. State coordination can accelerate infrastructure deployment and policy support. When government signals priority for AI hardware, supply chains respond faster. Testing cycles compress. The entire ecosystem mobilizes.

But this creates its own pressures. When everyone moves simultaneously, overcapacity looms. The AI hardware market could follow the same path as EVs. Rapid scaling, then consolidation, then export-driven survival. Winners will be companies that build capabilities without overcommitting to specific platforms.

The Real Competition: Speed vs Commitment

Three patterns emerge from the apparent chaos.