The AI Agent Split: Why China and Silicon Valley Are Building Different Futures

Picture this: It’s 7 AM in Beijing. Zhang Wei tells his phone, “Plan my weekend.” Within seconds, his AI agent has booked a restaurant for Saturday dinner, purchased movie tickets for Sunday afternoon, arranged a Didi ride, and even pre-ordered his favorite dishes–all confirmed and paid through WeChat. The entire process requires zero additional input.

Meanwhile, in San Francisco, Sarah Chen makes the same request to her AI assistant. She receives a curated list of restaurant recommendations, links to movie showtimes, and Uber fare estimates. Each action requires her explicit approval, separate app interactions, and individual payment authorizations.

This isn’t a story about feature gaps or technological capabilities. It’s about two fundamentally different visions for the future of AI agents–and why global technology companies are about to face their most consequential strategic decision since the mobile revolution.

The Philosophical Divide

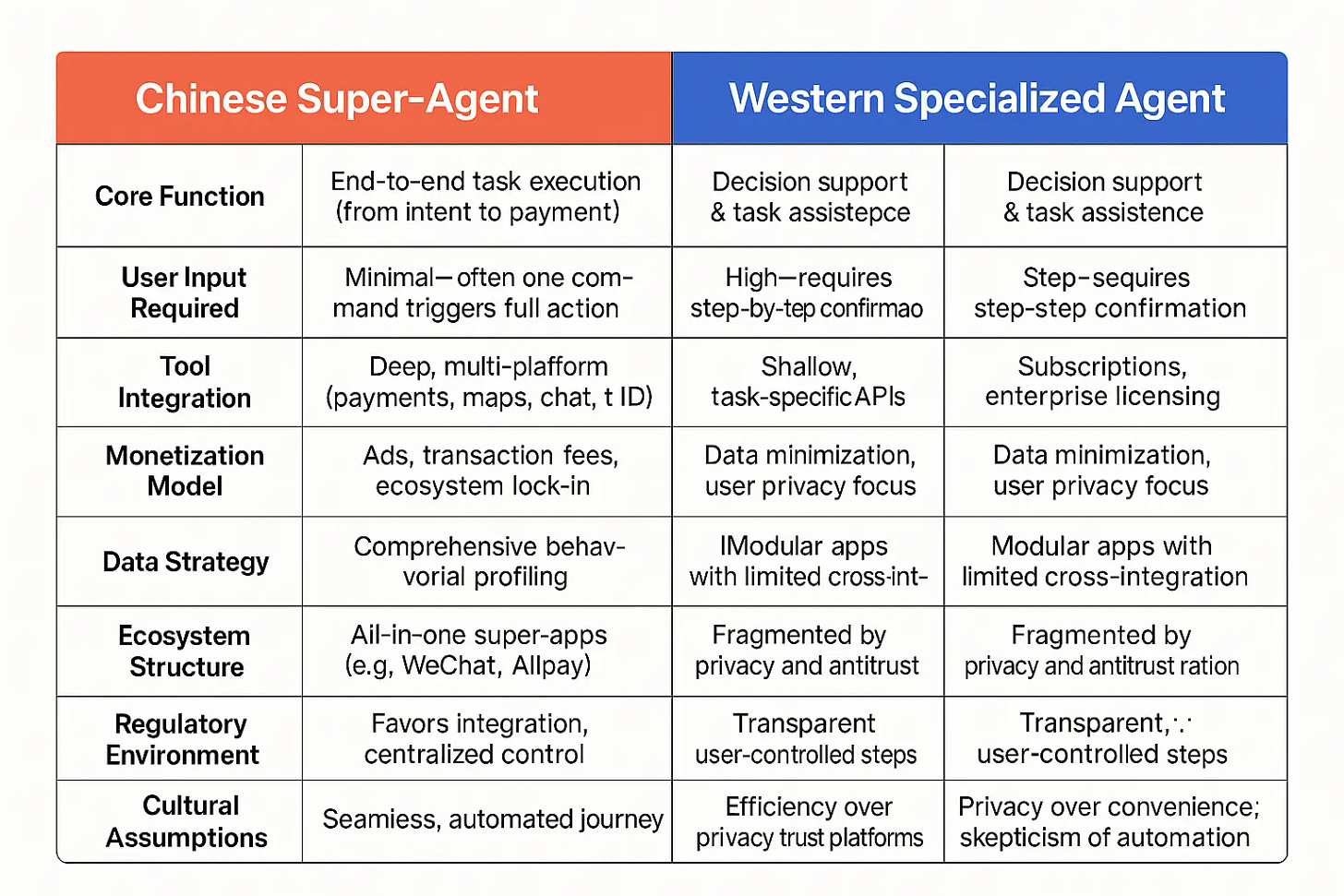

The recent frenzy around AI agents–sparked by Manus’s $75 million funding at a $500 million valuation just months after launch–has obscured a more fundamental split emerging in the industry. While the West debates whether agents should fetch information or complete simple tasks, China is already deploying “super-agents” that control entire user journeys from intent to execution.

This divide reflects deeper philosophical differences. Silicon Valley’s approach, exemplified by OpenAI’s Operator and Anthropic’s Claude, emphasizes user control, data minimization, and specialized functionality. Each tool excels at specific tasks–coding, writing, analysis–but operates within carefully defined boundaries.

China’s tech giants are building something entirely different. Baidu’s Xinxiang (心响) doesn’t just suggest restaurants; it books them. ByteDance’s Coze Spacedoesn’t just create spreadsheets; it integrates deeply with enterprise workflows. These aren’t tools–they’re digital surrogates that act on behalf of users with minimal oversight.

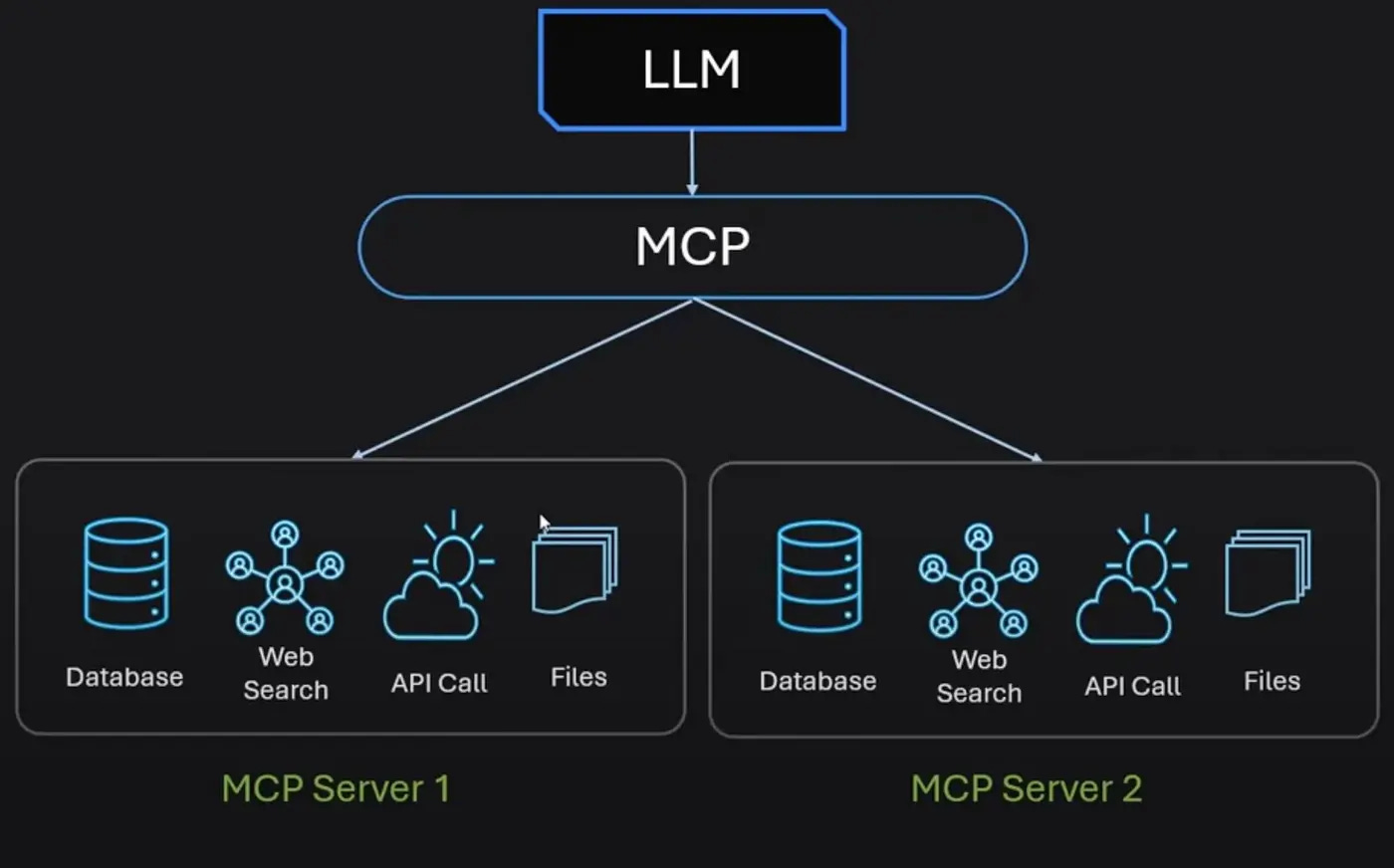

The MCP Wars: Infrastructure as Ideology

The recent explosion of interest in Model Context Protocol (MCP) reveals how technical standards become ideological battlegrounds. When Anthropic open-sourced MCP in November, it seemed like a neutral attempt to standardize how AI agents interact with external tools. Within months, it became the focal point of ecosystem competition.

Chinese tech giants didn’t just adopt MCP–they weaponized it. Baidu integrated MCP across its entire product suite, from search to maps to cloud services. Alibaba embedded it into Alipay, turning payment processing into an AI-native function. As one Chinese executive said, “MCP isn’t about interoperability; it’s about ecosystem lock-in at scale.”

This isn’t technological leadership–it’s strategic positioning for the coming platform wars.

Business Models: Ads vs. Subscriptions

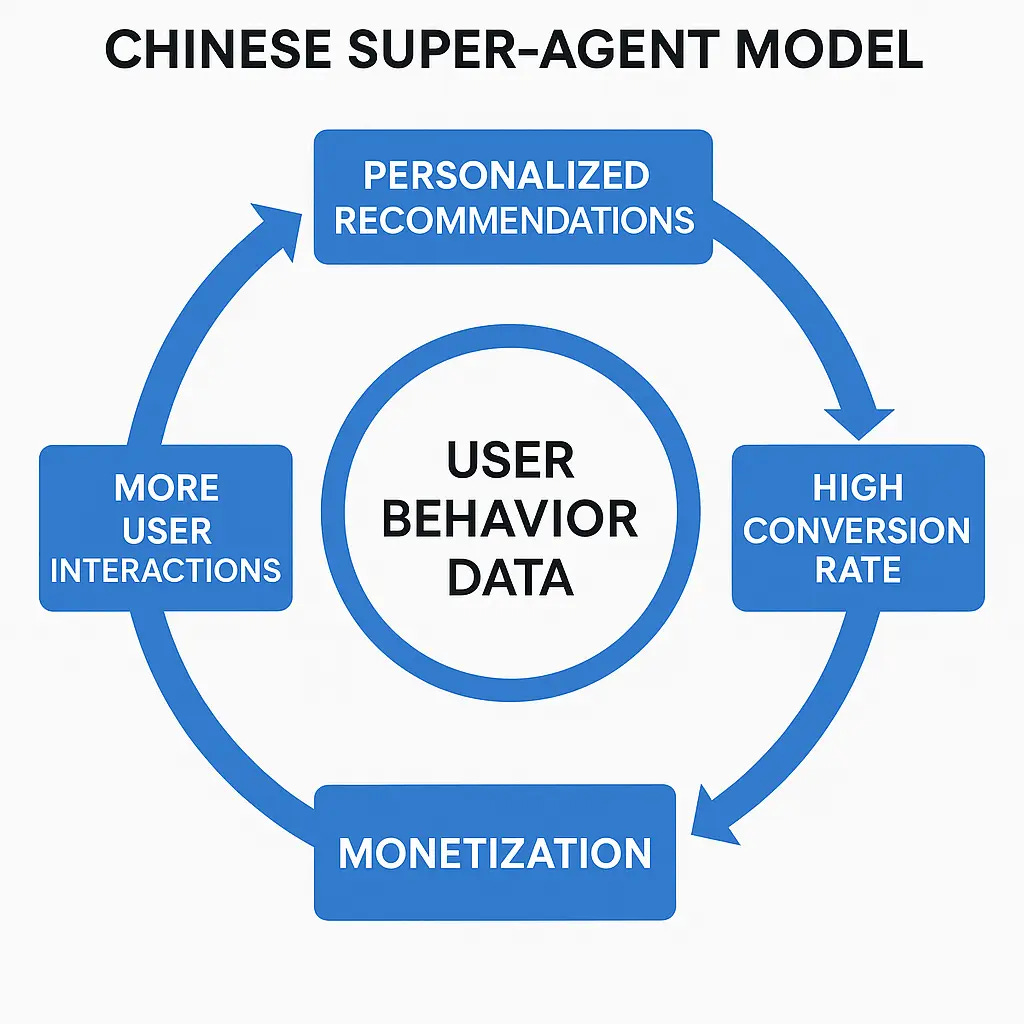

The agent divide extends to monetization strategies. Chinese super-agents are built on advertising and transaction fees, mirroring the country’s existing internet economy. When Baidu’s Xinxiang recommends a restaurant, paid placements influence rankings. When it books a ride, commission fees flow back to the platform.

Silicon Valley’s specialized agents rely on subscription models and enterprise licensing. OpenAI’s ChatGPT Plus, Microsoft’s Copilot, and Anthropic’s Claude Pro charge users directly for access. This isn’t just about revenue–it’s about data relationships. Subscription models prioritize user privacy; ad models require deep behavioral insights.

The implications cascade through the stack. Chinese agents need comprehensive user profiles to function effectively. Western agents operate on minimal data by design. As one venture capitalist noted, “We’re watching the privacy-convenience tradeoff play out at planetary scale.”

The Integration Imperative

The real power of Chinese super-agents lies in ecosystem integration. Baidu’s Xinxiang can access your search history, map location, payment records, and social connections–all within a single interaction. It’s not just convenient; it’s transformative. Tasks that require five apps in the West need zero in China.

This integration relies on China’s unique digital infrastructure. WeChat isn’t just a messaging app–it’s a platform OS. Alipay isn’t just payments–it’s identity verification. When agents tap into these systems, they inherit decades of user data and behavioral patterns.

Silicon Valley faces structural barriers to similar integration. Antitrust concerns prevent deep coordination between Google, Meta, and Apple. Privacy regulations limit data sharing. The result: Western agents excel at specific tasks but struggle with end-to-end workflows.

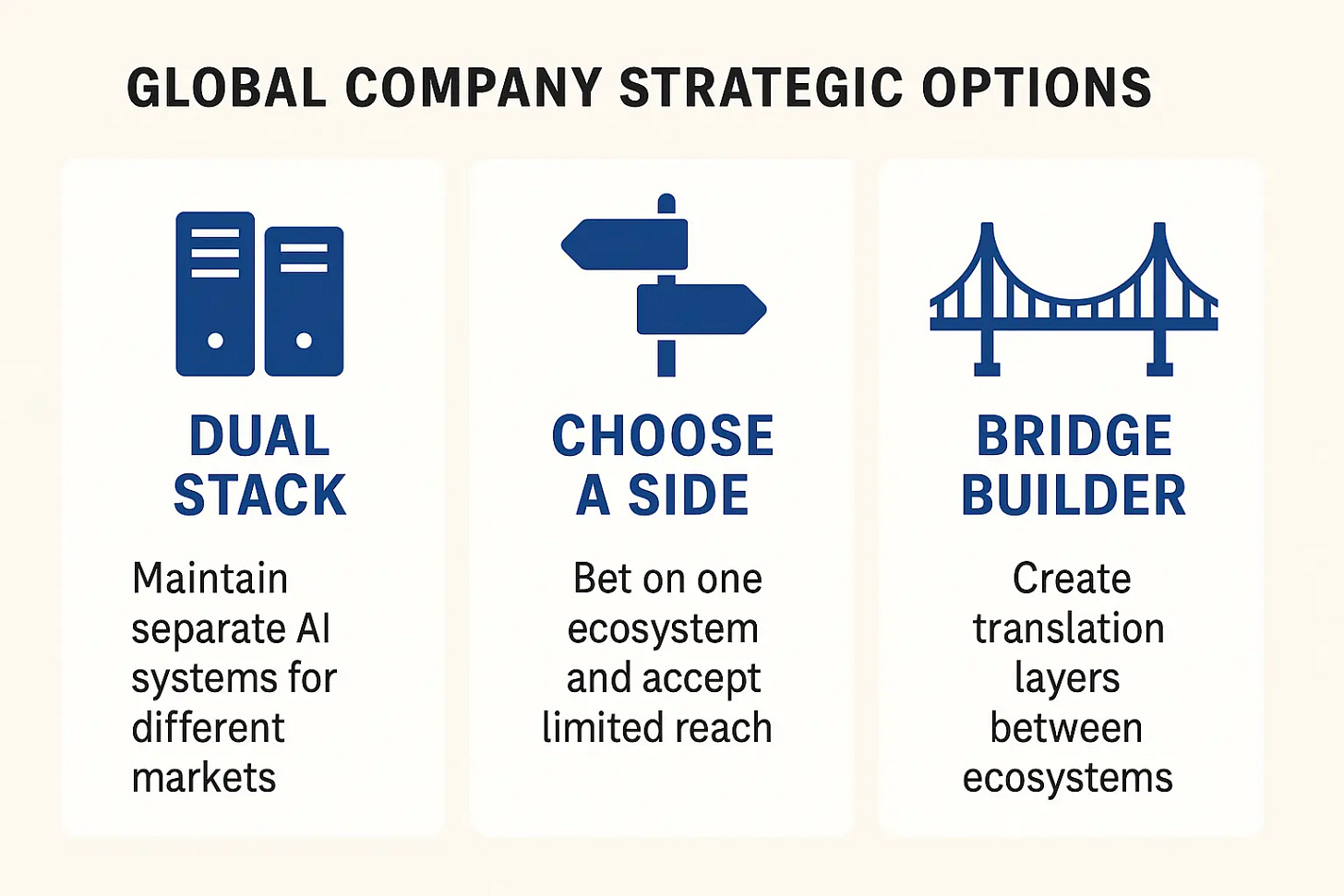

The Corporate Dilemma

For global companies, this split creates an unprecedented strategic challenge. You can’t deploy the same AI strategy in Shanghai and San Francisco. The infrastructure is incompatible, the regulations divergent, the user expectations opposite.

Three strategies are emerging:

Dual Stack: Maintain separate AI systems for different markets. Microsoft’s approach with Copilot (West) and Xiaoice (China) exemplifies this model. It’s expensive but preserves flexibility.

Choose a Side: Bet on one ecosystem and accept limited reach. Spotify’s decision to focus on Western markets while ceding China to local competitors shows this path.

Bridge Builder: Create translation layers between ecosystems. Ambitious but risky–no one has successfully built sustainable bridges between Chinese and Western tech stacks.

The Next Five Years

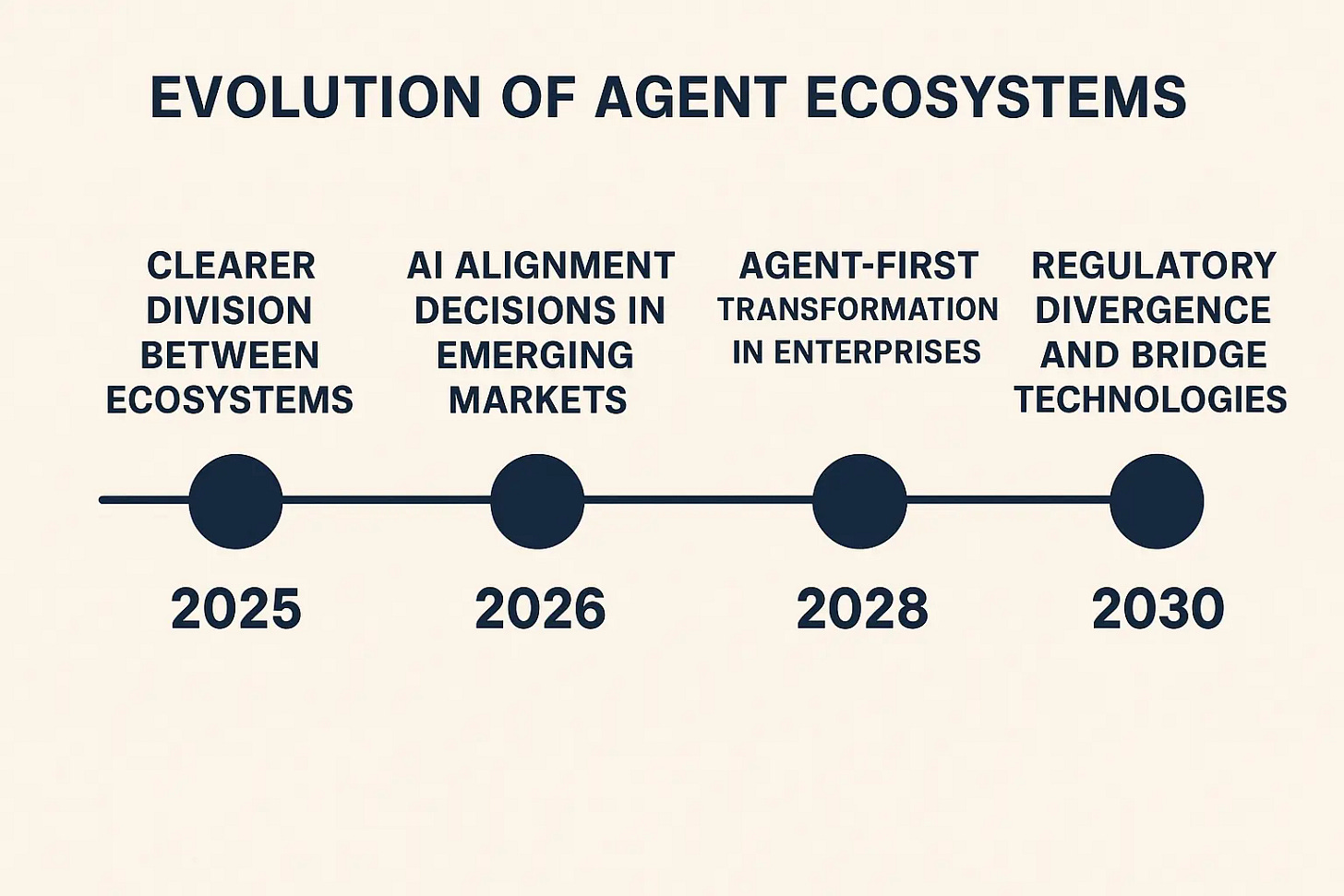

By 2030, I expect to see:

Ecosystem Crystallization: Clear boundaries between Chinese super-agent and Western specialized-agent ecosystems

Emerging Market Decisions: India, Southeast Asia, and Latin America choosing their AI alignment

Enterprise Transformation: Companies restructuring around agent-first workflows

Regulatory Divergence: New laws codifying different approaches to AI autonomy

Bridge Technologies: Potential breakthrough in cross-ecosystem compatibility

The winners will be infrastructure providers that serve both ecosystems, localization specialists who can translate between them, and early movers who establish dominant positions before boundaries harden.

The losers? Companies betting on global standardization, traditional software without AI integration, and anyone who delays their ecosystem choice until options narrow.

The Historical Parallel

We’ve seen this movie before. The iOS-Android split created two mobile ecosystems with different philosophies, business models, and user experiences. But that division was about devices and app stores. The AI agent split cuts deeper–it’s about how humans interact with all digital services.

The mobile wars taught us that ecosystem battles aren’t won by technology alone. They’re won by whoever best aligns technology with cultural values, regulatory frameworks, and existing market structures. China’s super-agents reflect a society comfortable with convenience-privacy tradeoffs. Silicon Valley’s specialized tools mirror Western emphasis on user control and data rights.

What’s different this time? The stakes. Mobile ecosystems changed how we access information. AI agent ecosystems will change how we make decisions, complete tasks, and navigate the world. The choice between super-agents and specialized tools isn’t just technological–it’s civilizational.